A NASA-funded project aims to use the Sun as a gigantic lens to peer into the far reaches of the cosmos — and search them for extraterrestrial biosignatures.

The project, led by Slava Turyshev at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, received $2 million in funding from the space agency’s Institute for Advanced Concepts back in 2020, an initiative that has supported plenty of other outlandish Moonshot projects over the years.

In a recent yet-to-be-peer-reviewed paper spotted by Universe Today, Turyshev teamed up with the Aerospace Corporation, a California-based nonprofit that operates federally funded research, to explore the feasibility of the idea.

Here’s what they propose: the mission would involve several small satellites that self-assemble at the solar gravitational lens (SGL) point, an epic journey that could take up to 25 years.

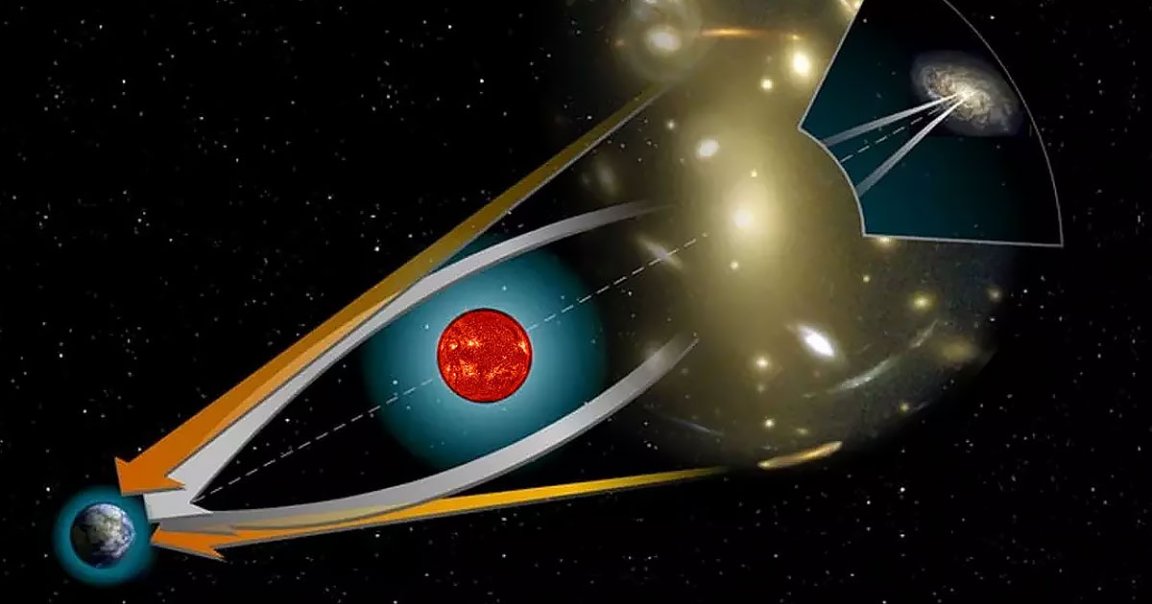

The SGL marks the spot where the assembled satellites, the Sun and a distant exoplanet target would form a straight line. The Sun’s gravitational field would then greatly magnify light from the exoplanet as it passes by, allowing the satellites to peer far beyond what has been possible so far.

That point also happens to be around 1,000 times the distance from the Earth to the Sun, which is several times the total distance NASA’s Voyager 1 probe has traveled over its 44 year journey, as Universe Today points out.

To cover the distance, the mission would take advantage of a solar sail, which are only starting to be tested by scientists.

In simple terms, a solar sail takes advantage of the tiny amounts of radiation pressure exerted by sunlight on large “sails” or mirrors, to slowly accelerate to high velocities.

Early experiments have shown promise, but the tech has never been tested over any great distance.

If such a mission were to ever become a reality — an astronomical if at this point in time — we could potentially peer into a different star system altogether without having to go there ourselves, Turyshev and his colleagues argue in their paper.

And that’s a tantalizing prospect the researchers argue is worth the time and effort.

“It is our only means, in the foreseeable future, to learn details about exosolar sister planets like our home world,” the team concludes.

READ MORE: A Mission to Reach the Solar Gravitational Lens in 30 Years [Universe Today]

More on gravitational lensing: NASA Releases Hubble Image of Most Distant Star Ever Seen