Researchers have come up with a new nanoparticle vaccine that they say can prevent or slow down numerous cancers in mice.

The team, led by University of Massachusetts Amherst biomedical engineering researcher Prabhani Atukorale, claims that the vaccine could one day prevent multiple cancer types from spreading in the body for high-risk patients.

“By engineering these nanoparticles to activate the immune system via multi-pathway activation that combines with cancer-specific antigens, we can prevent tumor growth with remarkable survival rates,” said Atukorale in a statement.

As detailed in a new paper published in the journal Cell Reports Medicine, the shot works by encasing adjuvants, which substances that increase or modulate the immune response to a vaccine, and melanoma peptide antigens, short amino acid sequences that can be recognized by the body, inside specialized lipid nanoparticles.

In one experiment, the team found that 80 percent of vaccinated mice that had been exposed to melanoma cells three weeks earlier remained tumor-free for 250 days, the full duration of the study. All unvaccinated mice, or mice vaccinated with a different formulation that didn’t involve nanoparticles, developed tumors — and none lived longer than 35 days.

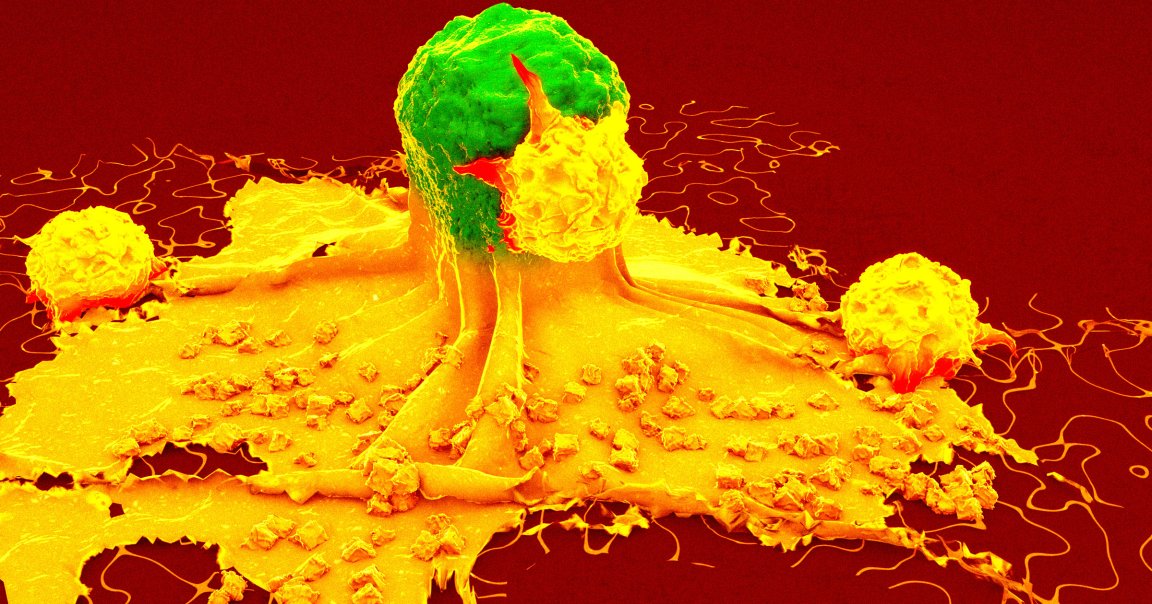

The nanoparticle vaccine allowed the mice’s immune system to produce T cells, white blood cells crucial for fighting infections and cancers, that could recognize and attack the melanoma successfully.

“Metastases across the board is the highest hurdle for cancer,” Atukorale added. “The vast majority of tumor mortality is still due to metastases, and it almost trumps us working in difficult-to-reach cancers, such as melanoma and pancreatic cancer.”

In a separate experiment, 88 percent of vaccinated mice exposed to pancreatic cancer rejected the tumor, while 75 percent and 69 percent of mice exposed to breast cancer and melanoma cells fought it off.

“The tumour-specific T-cell responses that we are able to generate — that is really the key behind the survival benefit,” said UMass Amherst researcher and first author Griffin Kane in a statement. “There is really intense immune activation when you treat innate immune cells with this formulation, which triggers these cells to present antigens and prime tumor-killing T cells.”

The treatment could prime the body to reject or prevent future cancers as well.

“That is a real advantage of immunotherapy, because memory is not only sustained locally,” Atukorale explained. “We have memory systemically, which is very important. The immune system spans the entire geography of the body.”

The team says the design could be applied to multiple cancer types as part of therapeutic and preventative regimes, a possibility currently being explored by the researchers’ new startup, called NanoVax Therapeutics.

However, it could take many years until we know if the same system can work in humans, let alone if it’s safe enough. Scientists are still working to identify the various risks of kickstarting the immune system to recognize pathogens, like cancers.

“Future studies incorporating additional markers of systemic inflammation and tissue-level pathology will be critical to fully evaluate tolerability and support clinical translation,” the researchers concluded in their paper.

More on cancer: People Who Don’t Smoke Are Getting Lung Cancer in Scary Numbers