Upon learning she had a breast cancer tumor, a Croatian virologist decided to grow her own viruses to fight the disease — a radical departure from medical norms that appears to have worked.

As the journal Nature reports, the risky self-treatment gambit undertaken by the University of Zagreb’s Beata Halassy has sparked a mix of controversy and admiration among her peers.

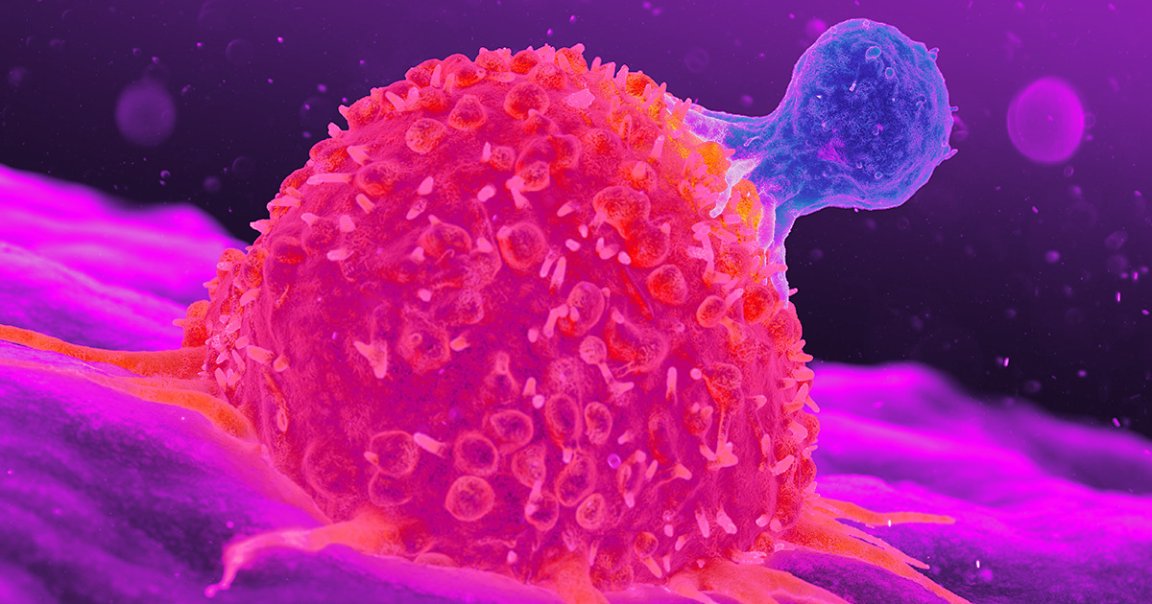

After learning in 2020 that she’d had a third recurrence of breast cancer following a mastectomy, Halassy researched oncolytic virotherapy (OVT), which as the name suggests uses viruses to fight disease by provoking immune responses. While it’s far from unprecedented and has been approved for early-stage metastatic melanoma, there are no government-approved OVT treatments anywhere in the world for breast cancer — which made the entire experiment dubious for Halassy, her doctors and colleagues, and the academic journal that ultimately let her tell her story.

The virologist had a colleague administer a mix of measles typically used in childhood vaccines and a vesicular stomatitis virus, both of which had been known to infect the cell type she was seeking to destroy and provoke the kind of immune response she needed. As the two-month trial progressed, the tumor shrank and detached from her muscles and skin, which made it easier to remove with surgery. When it was biopsied after removal, Halassy and her colleagues discovered that their gamble had paid off.

“An immune response was, for sure, elicited,” the virologist said.

This all took place back in 2020, meaning Halassy has now been cancer-free for four years now — but when it came to sharing her results with the world, she had difficulty.

After penning paper proposals about her experience and submitting them to journals, the researcher was met again and again with rejection. Most editors wouldn’t touch it, she notes, because they were concerned about the ethics of self-experimentation — and in particular, were worried others less knowledgeable may try to do something similar with catastrophic results.

Indeed, law and medicine researcher Jacob Sherkow of the University of Illinois-Champaign — who was not involved in Halassy’s paper — told Nature that journals have to toe the line between highlighting the knowledge gained from controversial self-experiments without promoting them as first-case course of action.

As a specialist who studied self-experimentation methods during the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, Sherkow said that he thinks Halassy’s study “does fall within the line of being ethical, but it isn’t a slam-dunk case.”

Ultimately, Halassy’s paper did find a home in the journal Vaccines, which published her “unconventional case study,” as its title notes, this past August.

Despite her publication difficulties, the virologist is proud of her experiment and people who brought it to publication.

“It took a brave editor to publish the report,” Halassy told Nature.

More on next-gen cancer treatments: Groundbreaking Ovarian Cancer Vaccine at an “Exciting” Moment, Lead Scientist Says