This article is part of a series about season four of Black Mirror, in which Futurism considers the technology pivotal to each episode and evaluates how close we are to having it. Please note that this article contains mild spoilers. Season four of Black Mirror is now available on Netflix.

Photographic Memory

If you could access any one of your memories in the same way you’d queue up a home video, which would you choose? It’s easy to think of all your good memories: births, achievements, an endless loop of the first time you fell in love.

What about the bad memories, though? The embarrassing or damning ones — the white lies, the speeding tickets, the arrests, or worse.

What about the worst thing you’ve ever done? Imagine if that memory was available to anyone that showed up to your door with the right badge. In “Crocodile,” the first episode of the new season of Black Mirror, investigators can do just that.

In the episode, an autonomous pizza delivery van appears to hit a pedestrian. The victim files a claim with his insurance company, and the investigator named Shazia starts interviewing witnesses to corroborate his story (they are legally required to cooperate). Shazia is equipped with a tool called a Recaller. Part lie detector and part video camera, the Recaller looks like a small television. When Shazia places a square node on the victim’s temple, the screen on the Recaller kicks on, displaying his memories.

“This accesses engrams, your memories of what happened,” Shazia says to the victim. “Now, they’re subjective. They may not be totally accurate, and they’re often emotional. But by collecting a range of recollections from yourself and any witnesses, we can help build a corroborative picture.” Shazia tries to jog the subject’s memory with different sensory triggers — a beer, some music. The more emotional a response, she explains, the more vivid the memory. Shazia watches the screen for more witnesses or investigative leads to verify the victim’s story.

The Recaller is an asset for to those with nothing to hide, those who seek justice or investigate fraud. But for those who have committed a crime, outsmarting it and keeping the secret intact becomes a bigger challenge.

That’s exactly what Mia is trying to do. She has a dark secret, but because she saw the accident, she’s required to subject herself to the Recaller. Her only goal is to escape with her secret intact.

Partial Recall

For better or for worse, our recalled memories don’t play like movies, and the human brain doesn’t work like a camera. Instead, the brain conjures a memory in a way “more akin to putting puzzle pieces together than retrieving a video recording,” Elizabeth Loftus, a cognitive psychologist at the University of California Irvine told Scientific American.

Because the brain’s method of storing and retrieving memories is less than perfect, fragments of unrelated memory can accidentally end up in the “puzzle” you’re trying to reconstruct. This could happen in recollections both important and banal, no matter whether you’re trying to remember what you had for breakfast last week, or providing testimony in a murder case. Eyewitness testimony is notoriously unreliable — 71 percent of convictions overturned by DNA evidence since 1989 were based on eyewitness testimony, according to The Innocence Project.

So, we can’t trust our own minds to accurately recall everything. Maybe technology could help us make up for where we’re lacking. Over the past decade, scientists have gotten closer to creating technology that could do just that, though nothing is quite as sophisticated as the Recaller.

In 2014, scientists successfully reconstructed faces based on subjects’ brain activity. During the study, subjects viewed 300 different faces while researchers recorded their brain signals using an imaging device called an fMRI. The researchers “trained” an algorithm to process the data from the scans, matching brain activity with particular facial features from the photos. When the scientists showed the subjects a set of new photos, the algorithm was able to interpret how the mind was processing faces and reconstruct them.

“It is a form of mind reading,” Marvin Chun, a professor of psychology, cognitive science and neurobiology at Yale University and one of the study authors, told Yale News.

Jack Gallant, a neuroscientist at the University of California, Berkeley, used subjects’ brain signals to take the mind-reading process beyond still images. In 2011, he and his team successfully reconstructed a video using brain scans of subjects who had watched the clips.

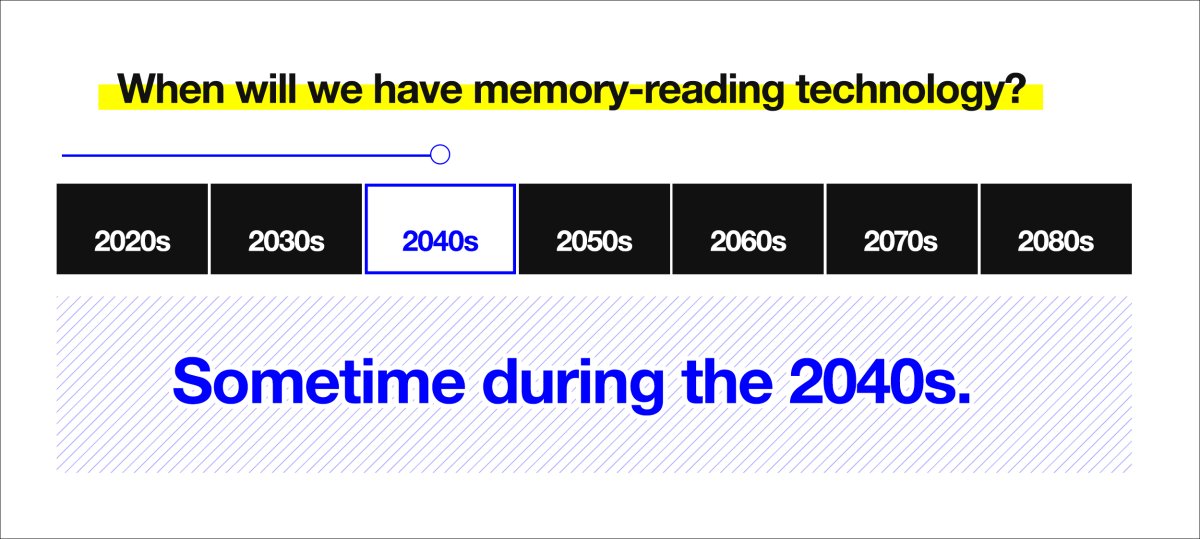

“This is a major leap toward reconstructing internal imagery,” said Gallant to Berkeley News. “We are opening a window into the movies in our minds.” Currently, the tech is limited. It can’t, for instance, reproduce memories or dreams in the same format. In fact, the researchers note that we are decades away from this possibility.

While, earlier this year, scientists did create a device that can “read the minds” of patients with locked-in syndrome, it could only recognize simple things — numbers one through nine and a few syllables in Japanese. It’s hardly a device like the Recaller. But it’s a profound step towards it.

Deceiving the Machine

Once we have technology that could reconstruct images from the brain, could we override it? Mia works hard to outsmart the Recaller. If today’s lie-detecting technology is any indication, she probably could have (had she had more time to prepare for her encounter with Shazia).

Polygraph tests have long been considered controversial, according to the American Psychological Association. The test measures vital signs such as rate of respiration, cardiovascular activity, and blood pressure — physiological processes the test’s creator used as stand-ins for the psychological act of lying. But the test is built on the wrong premise; there’s no established pattern of physiological reactions that are unique to lying. If you’re innocent but nervous, your heart rate will likely rise. Similarly, a dishonest person may not be anxious, depending on their mental state. As a result, courts often reject polygraph evidence because of how unreliable it can be.

Other biological routes could unlock a person’s true recollections to determine the veracity of a story, such as truth serum. But despite its name, the drug doesn’t totally stop a subject from lying. For the most part, it’s also illegal.

That’s not to say though, that this will always be the case.

“There is a large number of neural circuits that we are on the verge of being able to manipulate — things that govern states like fear, anxiety, terror and depression,” Mark Wheelis, a scientist at the University of California at Davis and a historian of chemical and biological warfare, told the Washington Post in 2006. “We don’t have recipes yet to control them, but the potential is clearly foreseeable. It would absolutely astonish me if we didn’t identify a range of pharmaceuticals that would be of great utility to interrogators.”

Until then, studying the brain more directly by connecting it with a machine may offer a more accurate picture of the truth. Technology that could effectively read minds could allow doctors to understand the thoughts of those who can’t verbalize, such as stroke victims or coma patients. It could decode your intentions, or help you type when your hands can’t move, or articulate your inner voice. Brain-computer interfaces, or merging human consciousness with artificial intelligence, seems to be where experts plan to go, though the technology has not yet caught up with their vision.

Of course, regulations also have to keep up; privacy and ethical concerns around brain-computer interfaces abound. What happens if someone were to hack into the device, for example? They could monitor our thoughts or even modify our actions. Is it possible that, someday in the far future, we will no longer have privacy, even in our own minds? Before this technology becomes widely available, researchers, lawmakers, and citizens will have to weigh in with potential solutions to keep our thoughts private in a new age of mind-reading tech.

It’s not far-fetched to think a device like the Recaller could be a reality, and perhaps even soon. The question will be who we allow to eavesdrop on our most private thoughts and memories.