A new trick uses precise ultrasound imaging — the same kind that lets parents-to-be see their kid before it’s born — to read and even predict activity within the brain.

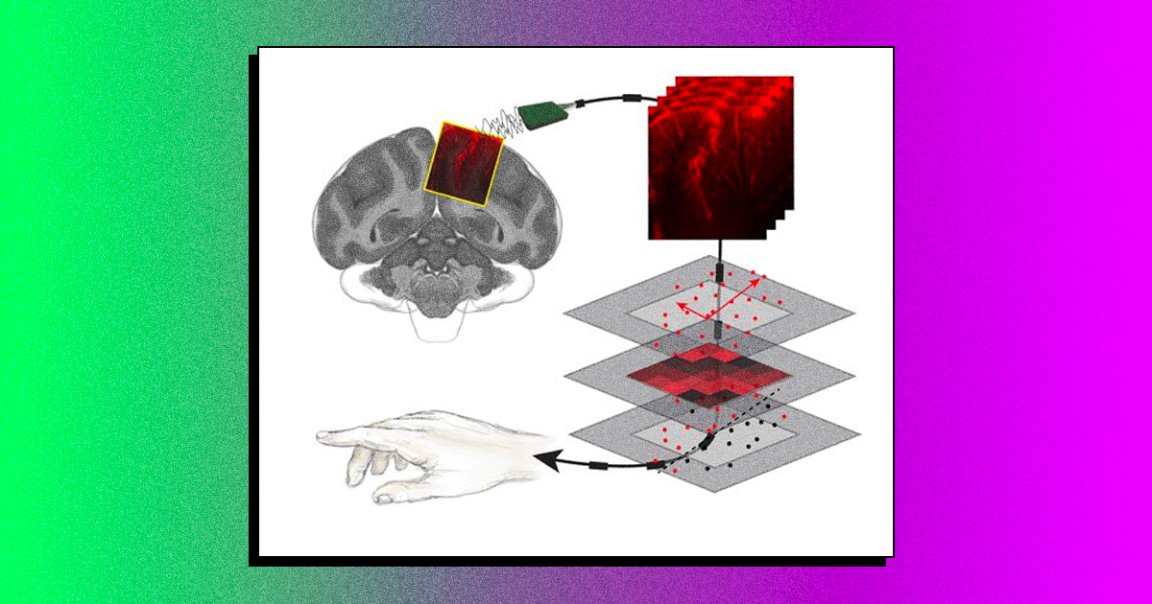

Scientists at Caltech were able to use ultrasound to listen in as blood sloshed around in different parts of the brain, which they quickly realized was a proxy for which neural regions were active at any given moment, according to an intriguing study published Monday in the journal Neuron. After running the data from a primate study into an algorithm, they also learned that certain patterns of blood flow not only matched but predicted what actions that primate was going to take and when they were going to do it — and there’s no reason it wouldn’t work in people, too.

All in all, that predictive neural imaging could give rise to a new era of brain-computer interface tech that’s both more accurate and less hazardous than other tools on the market, the scientists claimed in a press release.

“The first milestone was to show that ultrasound could capture brain signals related to the thought of planning a physical movement,” lead study author David Maresca said in the release.

The use of ultrasound could solve a major problem within the world of neural imaging and brain-computer interfaces. On one hand, we have implants and electrodes that can take extremely precise recordings of the brain, but because they require invasive and potentially harmful brain surgery, they’re only used in extreme cases like for patients with severe epilepsy. On the other hand, we have noninvasive brain imaging tools like functional MRIs or EEG arrays, but those either yield imprecise readings or require massive, nearly room-sized machines.

The ultrasound, however, seems to offer the best of both. Scientists could use it to image the brain down to a scale of 100 nanometers — the size of just ten individual neurons or one human hair — and didn’t need to perform brain surgery to do so.

“Functional ultrasound imaging manages to record these signals with 10 times more sensitivity and better resolution than functional MRI,” Maresca said in the release. “This finding is at the core of the success of brain-machine interfacing based on functional ultrasound.”