Understanding Cancer Cells

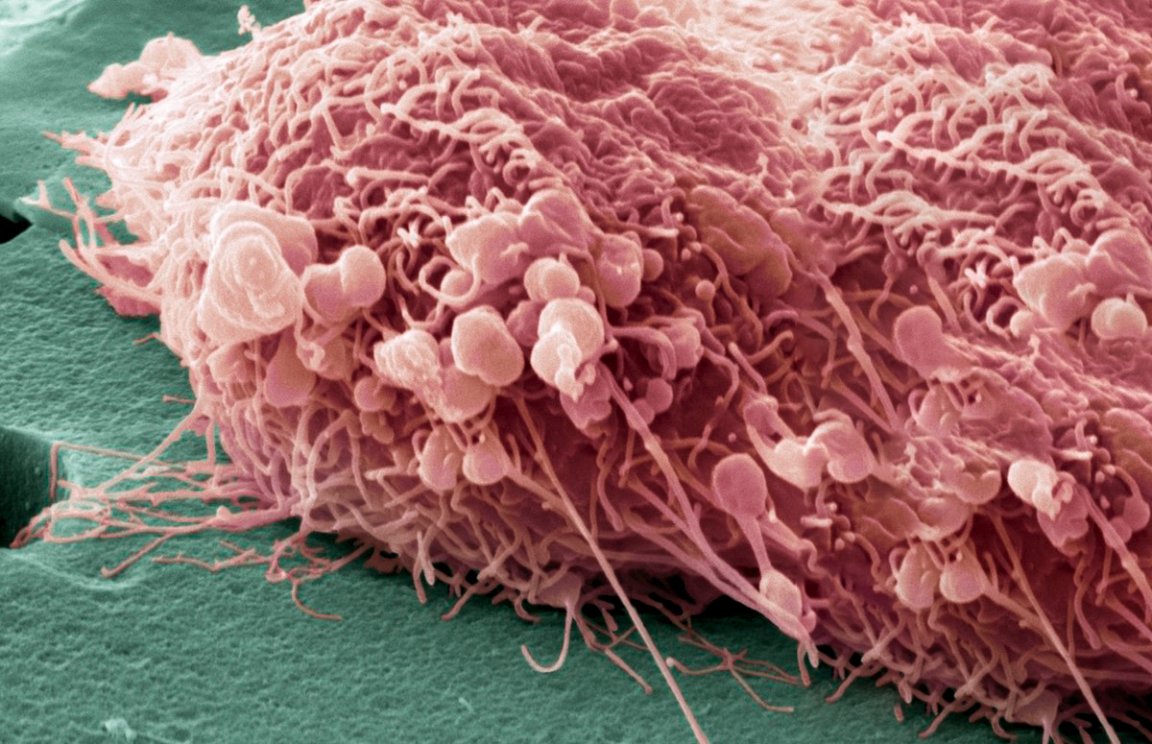

Treating cancer can be tricky: for one, cancer cells tend to spread quickly, known as metastasis — a behavior which sometimes goes undetected. As such, cancer remains a global problem, causing nearly 1 in every 6 deaths worldwide, according to the World Health Organization. 90 percent of those deaths occur when the cancer has metastasized. But what if the spread of cancer cells could be prevented? That’s the idea behind a study a team of researchers from Johns Hopkins University published in a recent issue of the journal Nature Communications.

The researchers realized the key is understanding what triggers metastatic behavior. “We found that it was not the overall size of a primary tumor that caused cancer cells to spread, but how tightly those cells are jammed together when they break away from the tumor,” lead author Hasini Jayatilaka said in a press release. The same kind of cellular behavior is also found in bacteria.

“At a fundamental level, we found that cell density is very important in triggering metastasis. It’s like waiting for a table in a severely overcrowded restaurant and then getting a message that says you need to take your appetite elsewhere.”

Improving Patient Outcomes

Prior to this study, the common notion about metastasis was that it occurred as a result of tumor growth. The team studied tumor cells in a three-dimensional environment mimicking human tissue and found that crowded conditions in cancer cells — not necessarily the tumor’s growth — is what triggers metastasis. They also identified the proteins — Interleukin 6 (IL-6) and Interleukin 8 (IL-8) — that cause cancer cells to spread.

“By doing this, we were able to develop a unique therapeutic that directly targets metastasis, not the growth of the primary tumor,” senior author Denis Wirtz explained in the press release. “This treatment has the potential to inhibit metastasis and thus improve cancer patient outcomes.”

Boston University professor Muhammad Zaman found this to be what’s so “exciting” about the findings of this study. “This paper gives you a very specific target to design drugs against,” he told the Baltimore Sun. “That’s really quite spectacular from the point of view of drug design and creating therapies.” The researchers note, however, that one drug or one therapy alone won’t do the trick. It’ll take drug cocktails, or a combination of various treatments that target metastatic behavior together with the body’s immune system, to win the battle against cancer once and for all.