The Link Between Cancer and Sugar

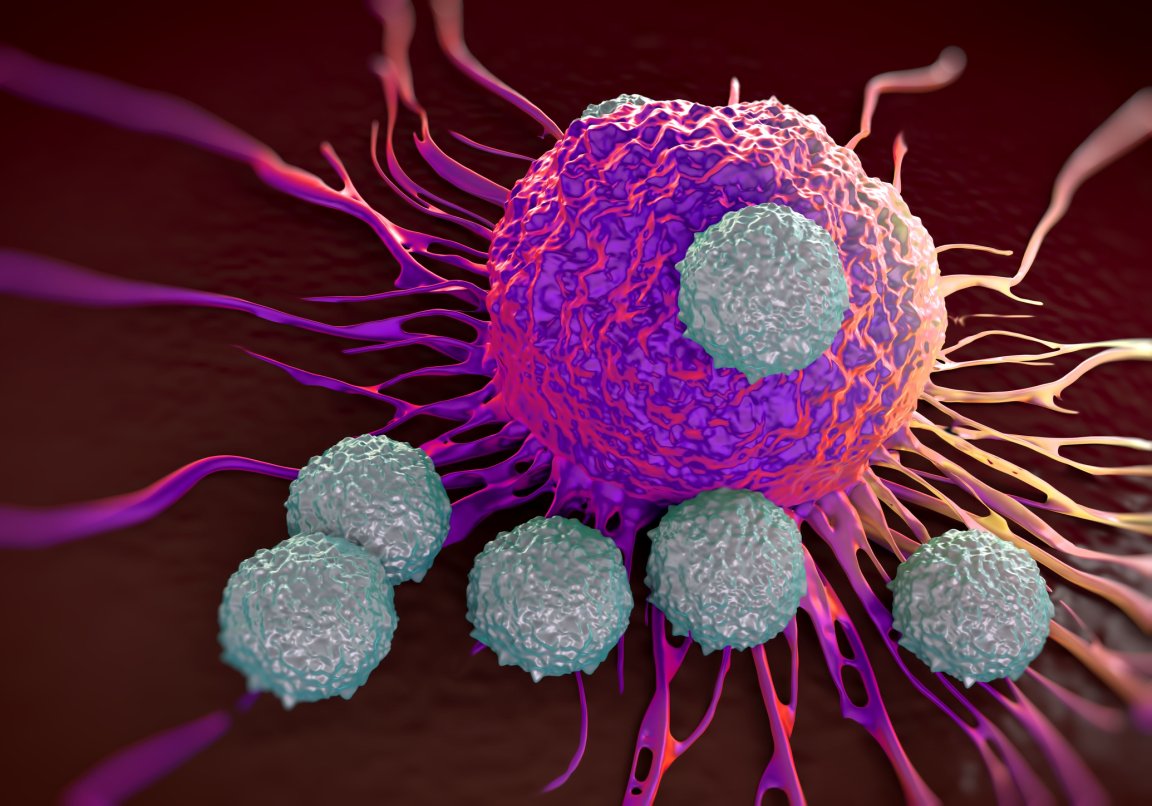

Over the years, scientists have dedication innumerable time, energy, and resources to cancer research in an attempt to discover — or develop — cures. One of the most notable observations science has made comes from cancer’s relationship with sugar. While the extent to which the two relate has previously been unidentifiable, a new study sheds light on the relationship.

Referred to as the Warburg effect, we know cancer (not unlike the human body) needs sugar for energy and to promote growth. The amount of sugar the cancerous cells require, however, is much higher than what healthy cells need — as is the rate at which cancer cells turn sugar in lactic acid.

Due to the nature of the Warburg effect, it’s been difficult to firmly establish whether it is a contributing cause of cancer, or the result of it. The latest study, the result of a nine-year long research project, has provided new insights about the metabolic process, revealing that it does, indeed, stimulate the creation of cancerous tumors.

“Our research reveals how the hyperactive sugar consumption of cancerous cells leads to a vicious cycle of continued stimulation of cancer development and growth,” said researcher and Prof. Johan Thevelein from KU Leuven in Belgium. “Thus, it is able to explain the correlation between the strength of the Warburg effect and tumor aggressiveness.”

Thevelein and his team used yeast to conduct their research, as yeast contains the same ‘Ras’ proteins found in cancer cells. It also has a highly active sugar metabolism. The team observed that the introduction of a large amount of sugar caused the Ras proteins to overreact, leading to an increased amount of yeast and cancer cells created.

“It is striking that this mechanism has been conserved throughout the long evolution of yeast cell to human,” added Thevelein.

Enabling Future Research

It has been proposed in the past that cancer cells could be starved of sugar, thereby preventing them from creating more cells. The problem with that method is there’s no way to inhibit cancer cells without also affecting healthy cells, though that may be slowly changing.

In any case, the research done by Thevelein and his team, published in the journal Nature Communications, makes such a treatment slightly more plausible. Thevelein said the team’s work will “provide a foundation for future research in this domain, which can now be performed with a much more precise and relevant focus.”

The research did not, however, offer an explanation regarding the cause of the Warburg effect. Additional research would be required to establish the phenomenon’s cause.

The fight against cancer has made significant progress this year: from the FDA approving new treatments, to a recent study explaining how a modified virus could kill cancerous cells. It’s unclear how far away we are from having cures, but many remain hopeful they will eventually be developed.