Colleges are back in session in the United States — and experts aren’t convinced schools are ready to handle a looming mental health crisis among students.

“I am so concerned,” Bernadette Melnyk, the Chief Wellness Officer and Dean of the College of Nursing at The Ohio State University, told Futurism. “I mean look at the statistics, prior to COVID, of mental health issues in college students. When we are getting 56 percent of students admitting that they feel things are hopeless or 46 percent of them feeling so depressed that it’s difficult to function? That was before COVID. What are we going to see during and following COVID?”

“This is a pandemic within a pandemic,” Melnyk added.

Many first-year and returning college students recently left their childhood homes for the start of a new academic year. Unless their school is operating online, that means moving into a dorm room and hoping that the deadly pandemic, which is still spreading throughout the nation, doesn’t come their way.

Compounding the problem, some college towns have already become COVID-19 hotspots, according to The Verge. And while managing the surge of new coronavirus cases will be a challenge, an oft-overlooked, equally-dire healthcare crisis will likely soon follow: colleges getting overwhelmed as they try to provide mental healthcare to everyone who needs it.

Unfortunately, over 600 American universities still plan to conduct classes primarily or entirely in person as of this article’s publication.

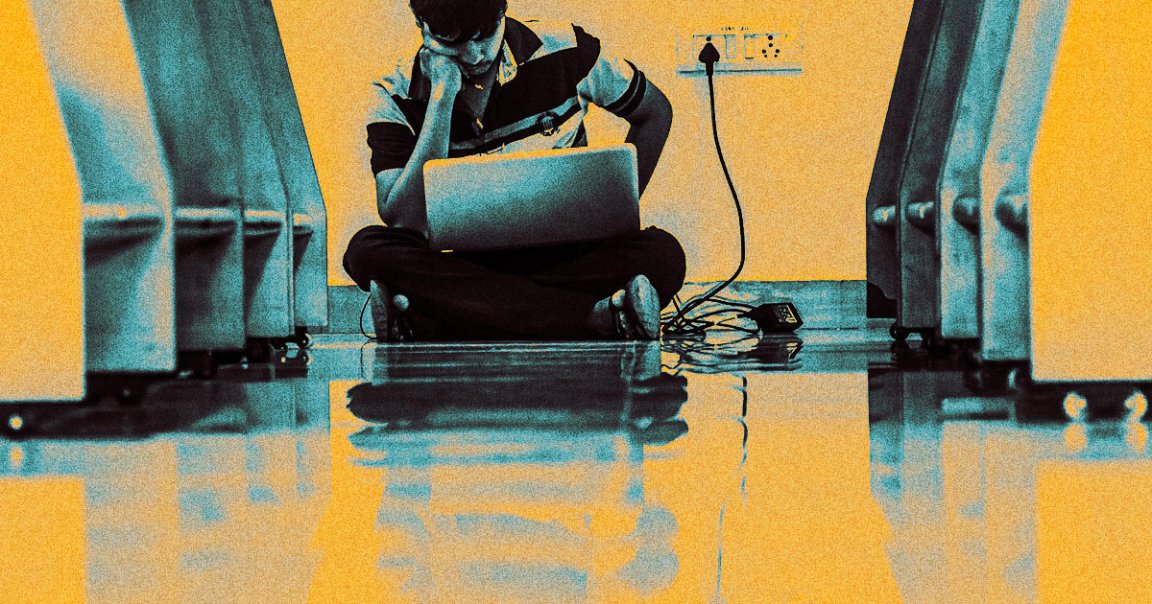

These pressures don’t exclusively target college students. But undergrads are in a unique position. Many are moving away from home for the first time and navigating a brand new chapter of their lives — only now they’re also expected to do so during a deadly pandemic that could affect them, their friends, or their family.

In other words, the dangers of COVID-19 are likely to make an already psychologically-taxing time even worse. Research published this month in the journal JAMA Network Open found that rates of depression have tripled among American adults since the pandemic began. Just over one in four Americans between the ages 18 and 24 have contemplated suicide during the same time period. About a third of graduate students reported signs of anxiety or depression, according to Nature News. The non-profit group United Way recently released research showing how some U.S. states, including Alabama and Texas, have nearly 1,000 residents for each mental healthcare provider. The national average falls at 438.

In light of all that, Melnyk believes that many colleges are unready.

“I think some [schools] have good plans,” Melnyk said. “But I’m sure many do not, seriously.”

Given the trifecta of increased need, limited access, and the costs of American healthcare, on-campus services may be the only support available to some students. But students told Futurism that in recent semesters, their schools have been woefully under-resourced for the realities of campus mental healthcare.

“I tried to make an appointment in November, when I was really needing help,” Libby, a recent graduate of Weber State University, told Futurism. “I got a call days later from the center, and they said they would be available after winter break, and that I should try again in January. When I tried again, they said their next available appointment was in late March. I had already sought care elsewhere because I was in severe need of psychological and psychiatric evaluation. I had to take on the cost myself because it was relatively urgent and I couldn’t wait that long anymore.”

Others stuck around for the wait, just to get such ineffective or limited care that the whole exercise felt worthless. Another student told Futurism that she reached out to her school’s counseling center because she felt suicidal, but was told she would have to wait weeks before she could make an appointment. When her session finally arrived, she was paired with a psychology graduate student who was so poorly trained that they started crying while the student described her story.

You don’t have to look too hard to uncover similar horror stories of students who were unable to get the mental healthcare they needed. Unless schools have really taken steps to improve, it’s unlikely that they’ll be able to care for everyone who needs support during the new semester.

Leandra Peloquin, a mental health case manager at San Francisco State University, handles off-campus counseling referrals for students. Peloquin was optimistic that mental healthcare providers are trying to do everything they can to help students, though she admitted that problems could arise.

“I feel we are at the point in society where we’ve made a lot of technological advances that enable us to connect to our students in different ways. I think our students are flexible. They’re adaptable,” Peloquin said. “I think that if the effective efforts are made so that students can connect, can receive the support that they need, that the university will be successful.”

She says that she expects mental healthcare to go smoothly at first this year, but that there’s the possibility the counseling center gets so many appointment requests that some students will have to wait, even though they always reserve space for any urgent crises.

“I think that it can be a struggle, right?” Peloquin told Futurism. “Just thinking about universities — we, for example, we don’t have a waitlist right now. Now as the semester gets deeper and deeper in — we’re looking later in the semester — we could perhaps have a waitlist if we’re at capacity. So it really depends on what the need is.”

The challenges that university counselors are about to face only amplify existing problems with how mental healthcare is offered. Melnyk has made a career talking to college presidents, counseling centers, and anyone else who could change the system about how the current paradigm’s focus on crisis management is a major disservice to students.

“First of all, we have got to recognize all the findings from research that show that when our students are struggling with mental health issues, their performance, their engagement, is going to be a lot worse,” Melnyk said. “What universities don’t typically do is help their students from the get-go.”

Basically, in order for a student to get the counseling they need, they must first suffer, then recognize that they need help, and then make and wait for an appointment. It’s no surprise, then, that two of three students who face mental health issues on campus ultimately leave school early.

“We live in such a sick healthcare system,” Melnyk said. “We really do. And we’ve got to flip that paradigm to wellcare and prevention, which would be so much more beneficial to the population — our health outcomes, our academic outcomes, and cost.”

But college students, especially first-years, are more likely to face these challenges without the social support network of close friends or family just by virtue of being on campus and away from home, perhaps for the first time.

Holding school entirely online comes with its own set of challenges. Take the University of North Carolina, which was declared a “clusterfuck” by its own student newspaper. UNC attempted to open in-person and immediately caused a COVID-19 outbreak before pivoting to online education.

Futurism contacted Dr. Allen O’Barr, a psychiatrist who serves as director of the UNC counseling center, before the school shut down. By the time we got in touch, UNC had already gone online and O’Barr was relieved about it.

“I’m really glad that we did it,” he said. “It’s safer for all even though I suspect that it will have big financial implications.”

Across the board, universities have adapted to the pandemic by offering mental healthcare and counseling remotely, through private video or phone calls. Unfortunately, even then, students can get left behind.

Doctors are licensed to practice at the state level. For telehealth purposes, that means that the practitioner and the patient must be in the same state to have a session without running afoul of the law. So even if a school’s counseling center is up and running and has adequately prepared to offer teletherapy, students who live out of state aren’t allowed to access it.

O’Barr told Futurism that he and his team at UNC need to evaluate the laws on a state-by-state basis to see if they’re allowed to help students. At San Francisco State, Peloquin says she and a colleague put together a written guide and, if needed, can hop on the phone to help out-of-state students seek out mental health resources in their area.

Melnyk points to the steps she’s taken at Ohio State as a model for the nation. Namely, she says, schools must preemptively promote wellness and preventative care rather than playing whack-a-mole with emergencies.

“From freshman year — early — teach evidence-based techniques that we know are protective against mental health disorders,” Melnyk recommends. “Like mindfulness, cognitive-behavioral skills building. I look at this as mental resiliency, right? Equipping ourselves with those resiliency skills that we know are protective factors against mental health disorders.”

And, in that regard, Melnyk says that students need to step up as best they can.

“We can’t place this 100 percent on universities. Our students have to take responsibility for their mental health too. They need to make their mental health a priority. They have to engage in healthy habits that we know are good for mental and physical health.”

If there’s any sort of upshot to all of this, experts tell Futurism, it’s that we as a society might learn from our mistakes and build a mental healthcare system that’s better, more accessible, and more compassionate.

“This pandemic has been a great tragedy for many people and it seems it will continue to be for a while,” O’Barr told Futurism. “There is no disregarding the suffering. That said, I believe that it has caused us to sit still long enough to see inequities in our national and global system that privileged individuals could afford to overlook in the pre-pandemic world.”

“I truly believe that we have a chance to emerge as a better nation and global society if we can find a way to all work together on this,” he added.

Melnyk is encouraged that more schools are looking for Chief Wellness Officers or asking her to share her expertise, but these changes — especially the paradigm shift she advocates for — can take years to implement when faced with institutional barriers and persistent stigmas that surround mental healthcare.

“But we have an urgent situation here going on,” Melnyk said. “We’ve got so much research to show that when students don’t have good mental health, by golly, their grades aren’t going to be good. They’re not going to show up to class, they’re going to slip.”

“I don’t know that people really understand that to the degree they need to understand that.”

If you are experiencing suicidal ideation and need help, please call the 24/7 National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 800-273-8255 or text “HELLO” to the Crisis Text Line at 741741.