Targeted and Edible

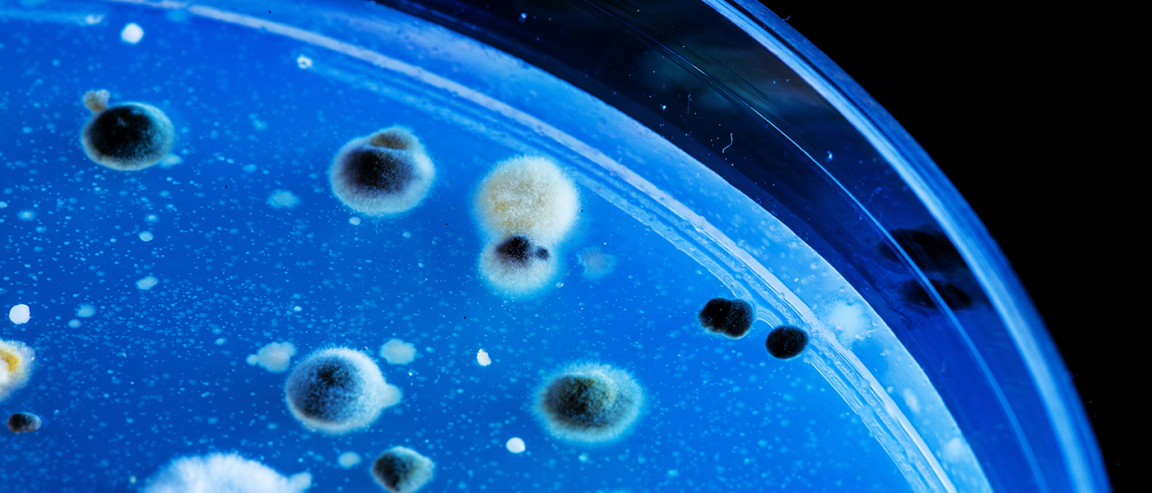

As antibiotic resistance continues to grow, scientists are desperately trying to figure out how to best fight bacterium like Clostridium difficile, which can cause fatal infections in hospitals and nursing homes. C. difficile has been ranked by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) as a top drug-resistant threat responsible for about 15,000 deaths per year. Several means are being explored to counter the pandemic, the most recent coming from a project funded by the National Institute of Health.

The proposed solution uses CRISPR, the world’s most precise and efficient gene editing technology currently available. Jan-Peter van Pijkeren, a food scientist from the University of Wisconsin-Madison, is creating a probiotic cocktail that patients can swallow as a liquid or pill.

The cocktail of bacteria will include a bacteriophage – a virus that infects bacteria – capable of carrying a customized, false, CRISPR message to C. difficile. This message would cause C. difficile to make lethal cuts to its own DNA.

Better Than Antibiotics

Currently, this probiotic is still in its early stages, according to van Pijkeren, and is yet to be tested on animals. Luckily, similar studies have proven the effectiveness of bacteriophage-delivered CRISPR in killing bacteria. However, researchers still have some concerns.

“The downside of antibiotics is they are a sledgehammer that depletes and destroys the gut microbial community,” van Pijkeren said to the University of Wisconsin-Madison. “You want to instead use a scalpel in order to specifically eradicate the microbe of interest.”

CRISPR is ideal for this use because such drugs would be very specific to the user. They could kill a single species of germ while leaving good bacterial untouched. In contract, regular antibiotics kill off both good and bad bacteria, leading to resistance. If proven successful, CRISPR could become, not just the world’s most effective gene editing tool, but also the best bacteria-killing technology available. While this is a long way off, it still gives hope to thousands.

“As long as we house patients together in a hospital or in a nursing home and we give a lot of them antibiotics we’re going to have a problem with C. difficile,” says Herbert DuPont, director of the Center for Infectious Diseases at the University of Texas to MIT Technology Review.