Desperate Times

The opioid epidemic continues to sweep across the U.S. as manufacturers flood towns with millions of opioid pills. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimate that an average of 115 Americans die every day from an opioid overdose.

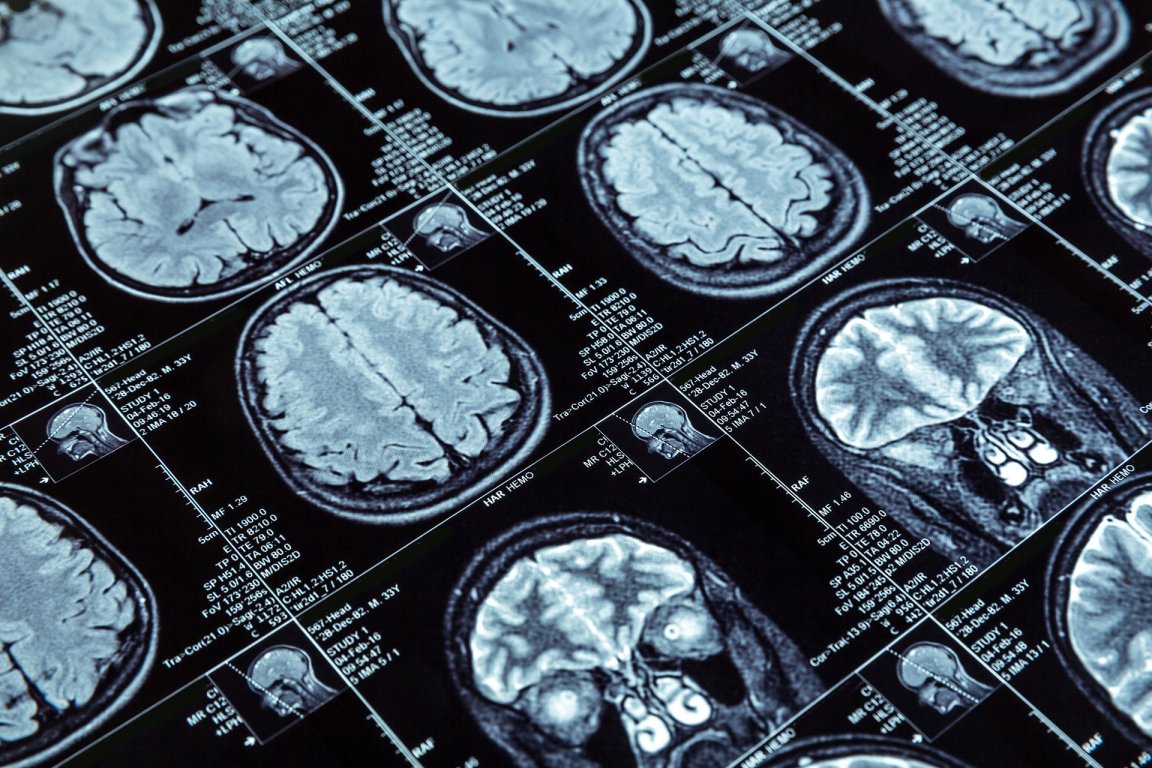

Researchers and medical professionals are scrambling to find treatment options for opioid addiction. In November 2017, the FDA approved a device that transmits electrical pulses to the cranial nerves associated with pain processing, to alleviate opioid withdrawal symptoms in patients. Now, another treatment — set to begin clinical trials later this year — will take that approach even further, implanting electrodes directly onto the brain.

The implant — controlled by a pacemaker-like device — will send electrical signals to target the reward center of the brain, hopefully minimizing the over-activity that is responsible for the addictive behavior. Known as deep brain stimulation (DBS), this type of therapy is currently used to treat tremors associated with Parkinson’s disease, and is undergoing testing for use in Alzheimer’s and other brain disorders.

The one drawback? Inserting the implant requires major invasive surgery. Neurosurgeons must make an inch-long incision in the scalp, drill a dime-sized hole in the skull, and add the implant.

Call For Desperate Measures

There are some major risks associated with the therapy. According to a study conducted by addiction researchers Wayne Hall and Adrian Carter in 2011, “Insertion of stimulating electrodes can cause serious infections and produce cognitive, behavioral, and emotional disturbances.”

Even the neurosurgeon hired by West Virginia University to conduct the trial, Ali Rezai, makes sure to tell patients receiving the implants that there’s a one percent chance of severe complications. Due to these risks, the treatment may have to be a last resort effort for addicts who have exhausted all other options and still failed to kick the addiction.

Rezai has a steep uphill battle ahead of him, even in terms of patient recruitment. Past studies hoping to investigate the effectiveness of the therapy ran into snags at this first crucial stage. A 2010 study conducted at the University of Amsterdam’s Academic Medical Center by Judy Luigjes was only able to recruit two of eight participants. “We had a long screening procedure, hoping people weren’t deciding impulsively. Few wanted to go through with it. A lot of it has to do with fear of the procedure,” Luigjes told STAT.

Rezai predicts that his study could lead to DBS becoming a widespread option for opioid addiction treatment by 2025. But eight years is a long time to wait when the current epidemic is costing the U.S. nearly $80 billion annually in increased healthcare costs and addiction treatment.

In the meantime, its critical that researchers continue working towards discovering new addiction treatments, and lawmakers continue to hold drug manufacturers financially accountable for their role in the nation’s devastating opioid epidemic.