A new treatment for the chronic and debilitating disease multiple sclerosis (MS) has doctors throwing around phrases like “game changer.” Newsweek said it could “revolutionize care for one million Americans.” Alphr called it a “breakthrough.”

There are just a few problems, however: The experimental procedure is under scrutiny from regulators, the experiment’s web site may have overstated the effectiveness of the not-yet-proven treatment, and patients have to foot the bill.

Oh, and no one has seen the study yet.

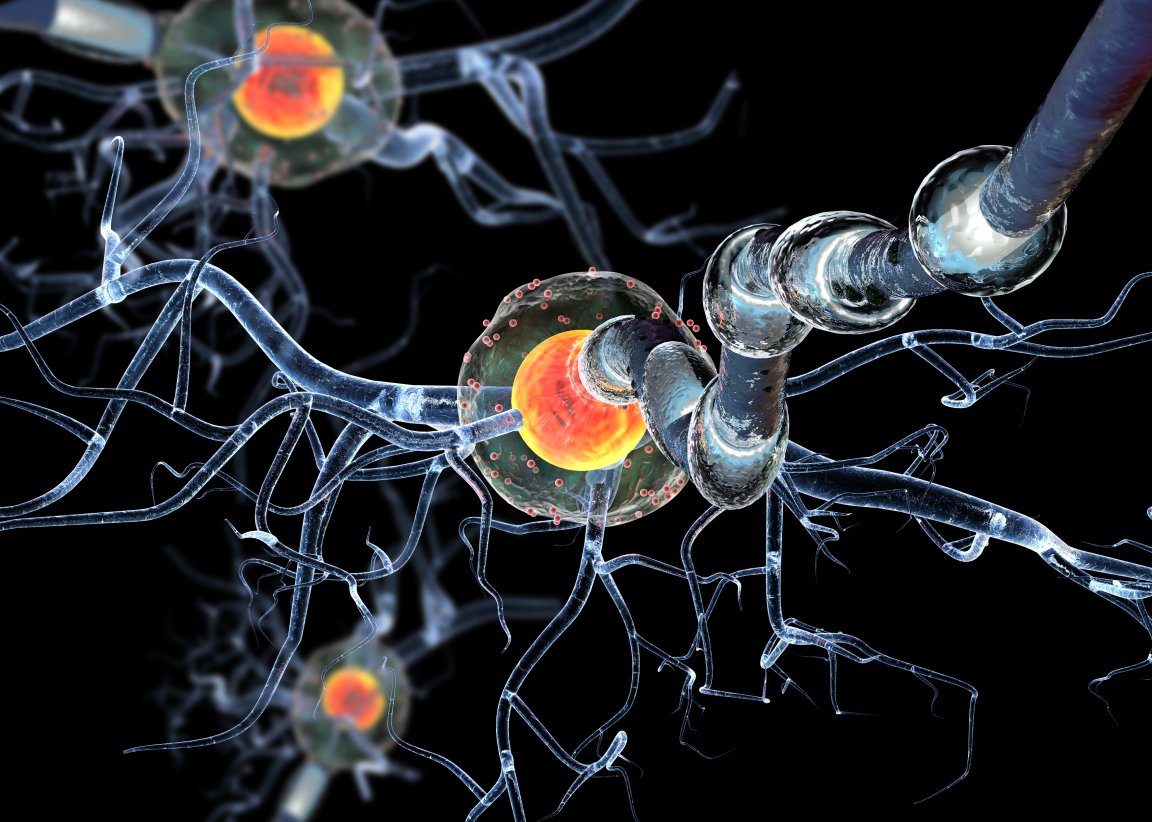

MS causes the immune system to attack a person’s nerve cells. According a press release, the treatment combats the disease by using chemotherapy to suppress their immune system, then “resetting” it with an injection of their own stem cells taken from the blood and bone marrow.

The trial involved over 100 patients with relapsing remitting MS, in whom the disease oscillates between attacks and periods of remission. Patients were recruited from cities all over the world— Chicago, United States, Sheffield, United Kingdom, Uppsala, Sweden, and Sao Paulo, Brazil.

For at least one patient, it appears to have worked. The BBC met a now symptom-free patient who was once bedridden but is now living free of MS, she says. After the treatment, the 36-year-old woman from Rotherham in the U.K. says she was healthy enough to carry and give birth to her first child — something she thought she would never be able to do.

After a year, only one patient had relapsed in the stem cell group, compared to 39 on the standard treatment, the BBC reports. After three years, the stem cell treatment was ineffective in 6 percent of patients, versus 60 percent in the standard treatment group. The patients who underwent the stem cell transplant saw their symptoms improve overall.

Sounds good, right? But press releases and media reports don’t provide nearly enough information to call something a “breakthrough.”

The study with all the details to answer these questions has not yet been published, nor has it been peer-reviewed. Richard Burt, the chief of immunotherapy and autoimmune diseases at the Northwestern University’s Feinberg School of Medicine and lead researcher on the study, plans to submit the study for publication sometime in May, a press officer from Northwestern University told Futurism.

The results reported in the BBC piece are just the preliminary findings. And that leaves a number of questions still unanswered — are these results permanent? What are the risks? Who isn’t suited to have their immune system wiped out through aggressive chemo?

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has also flagged some serious issues in the study’s protocol. If that sounds boring and bureaucratic, think of it this way: for a few months, the lead investigator somehow forgot to report a number of nasty side effects of the treatment, including chest infection and the worsening of conditions as diverse as vertigo, narcolepsy, stuttering, and hyperglycemia, among others.

One thing we know for sure? It’s real expensive. The BBC noted it cost patients £30,000 ($42,000) to receive the experimental treatment, but biomedical scientist and science writer Paul Knoepfler, who has been following the trial since last year, says it ran some patients between $100,000 and $200,000.

Clinical trials are expensive, so it’s not totally uncommon for some of the cost to be passed on to patients that want to enroll, as long as they are clear about what they are getting.

But it’s patients’ expectations where things get a little murky. In his article, Knoepfler notes how the trial’s homepage, now password-protected but still visible through Wayback Machine, seems to overpromise: the homepage indirectly references the word “cure” in several places, showcasing headlines that mention it (though in an interview Burt said he wouldn’t use that word). Overall the page makes some awfully big claims for an experimental treatment, Knoepfler notes.

And for people who decide to fork over the astronomical sum needed for the treatment, there’s a handbook offering some helpful fundraising ideas. Options include: “call your local media including the news stations, TV stations, newspapers and radio. Encourage them to do a special feature or human interest story for the cause.” Selling one’s private life to the media seems to benefit the researchers a bit more than the person desperately trying to raise funds for what they see as a life-changing treatment.

And if the treatment does become approved by regulators, those “helpful fundraising ideas” will be even more necessary for patients. In the U.K., Susan Kohlhaas, director of research at the MS Society, told the BBC that the stem cell transplant “will soon be recognized as an established treatment in England — and when that happens our priority will be making sure those who could benefit can actually get it.” That’s great for British patients that have the country’s National Health Service footing the bill. What about the U.S., where healthcare is not public and definitely not for all?

The preliminary results of the study are exciting, no question. But calling the treatment a “game changer” is, undoubtedly, premature. Until the study is properly peer-reviewed and published, patients looking for a breakthrough intervention for MS should proceed with caution. And keep their personal stories, and their hard-earned cash, to themselves.