No Need To Panic

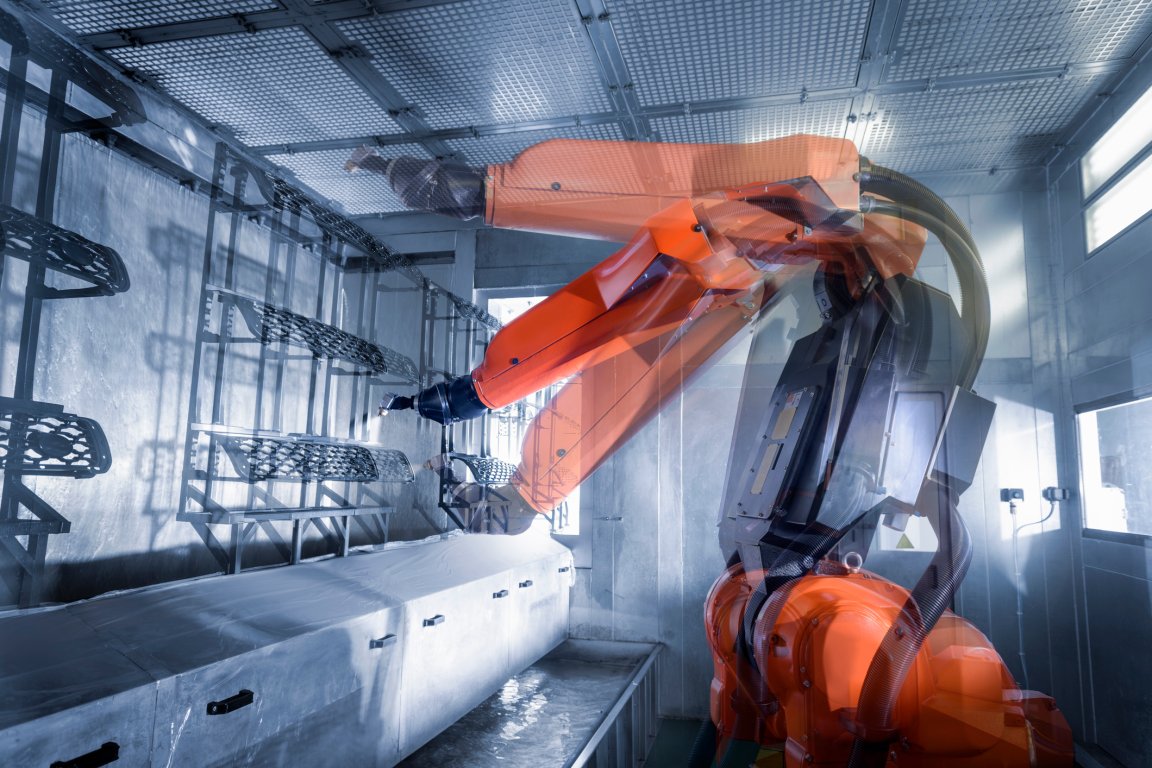

You’ve probably heard that a robot is going to take your job. It’s an oft-repeated refrain, heralded in article headlines and speeches from luminaries such as Elon Musk and Stephen Hawking. Some experts predict that anywhere from 38 to 57 percent of jobs could be automated in the next few decades, depending on who you ask, and the jobs aren’t limited to any one industry. Automation threatens to eliminate or limit jobs such as waitstaff, truck drivers, factory workers, accountants, cashiers, and retail employees, according to a recent report from PBS.

But to other experts, these apocalyptic predictions are overblown. Even worse — they fear that the warnings themselves could slow the progress of innovation, leaving society worse off.

Two economists from the Information Technology and Innovation Foundation (ITIF) decided to clear up the debate once and for all. In May, Robert Atkinson and John Wu published a report titled “False Alarmism: Technological Disruption and the U.S. Labor Market, 1850–2015.” By analyzing data about occupational trends from the United States Census over the past 165 years, the duo concluded that those dark predictions of future employment are based on faulty logic and incorrect analyses.

For their report, the researchers focused on identifying increases or decreases in occupations that could be attributed to technological innovations. For example, the significant increase in the number of automobile repair workers following the production of the Model T and the decrease in the number of household workers following the invention of the washing machine were both identified as examples of technology-caused change. The researchers do admit in the paper that this method of determining whether technology affected the growth or decline of an occupation was “clearly a judgement call and subject to errors.”

Based on this methodology, Atkinson and Wu reached three primary conclusions. One: that the total number of jobs has changed very little over the past 20 years. Two: Growth in existing industries has made up for jobs lost to automation (example: a factory replaced workers with machines on the production side, but invested the money it saved into new jobs in sales and marketing). Three: Between 2010 to 2015, the U.S. lost the fewest jobs to automation.

Several experts were on board with the researchers’ report. Tech strategist Simon Wardley hailed the report as “a fascinating read“; economics and business journalist Robert J. Samuelson praised the report for reminding readers that, in the past, entire occupations have been wiped out, and society hasn’t drowned in unemployment.

History, others agree, is a pretty good reason to be skeptical that technology will lead to widespread job loss.

“The fact is that there are waves of historical change in technology; they come, they go, there is nothing inevitable about them,” Robert Friedel, professor of the history of technology and science at the University of Maryland, said in an interview with MeriTalk, a website geared towards government IT experts. “We have absolutely no reason, I would argue, to suggest that that pattern is somehow permanently broken.”

A Bad Attitude

There are real consequences to believing those ominous predictions, Atkinson and Wu note. In fact, these warnings of technological disruption could ultimately be as detrimental as a robot takeover itself.

In their report, the researchers assert that the public could become wary of technology if they hear individuals they respect say that robots are coming for their jobs. This could cause technological progress to grind to a halt. Humanity would accept stagnation over innovation.

This anti-tech attitude is far from new — from 1811 to 1813, Luddites destroyed machines in England to protest textile automation. In 1830, British agriculture workers attacked the threshing machines that were rendering them expendable.

It’s hard to ignore the echoes today. In 2014, Parisian taxi drivers slashed the tires of Uber drivers in an attempt to gut their tech-enabled competition. Some governments have banned ride-share apps altogether for fear that taxi drivers will be left in the lurch, and others are already putting forth legislation to prohibit self-driving cars for fear they will cause more drivers to lose their jobs.

In the summary of their report, Atkinson and Wu urge policymakers to encourage technological innovation and push back against any organizations or workers that seek to stymie it. On that front, most thought leaders seem to agree. “If we slow down progress in deference to unfounded concerns, we stand in the way of real gains,” Mark Zuckerberg wrote in an op-ed for Wired; Bill Gates told Quartz that society could miss out on technology’s positive impact if fear trumps enthusiasm and inhibits innovation.

Regulators and industry leaders, then, should tread a delicate line. They should support technological advance and help society adopt it. But they would be foolish not to prepare for the possibility that automation could supplant millions of workers.

Preparedness Starts At The Top

Government leaders have to spearhead this preparation, Atkinson and Wu note in their report. If automation does profoundly disrupt the workforce, legislators will need to consider which policies will best mitigate this disruption. Bill Gates has suggested taxes on robots; Alan Barber, director of domestic policy at the Center for Economic and Policy Research, thinks work-sharing initiatives could help. Gerlind Wisskirchen, vice chair of the International Bar Association’s global employment institute, has suggested “human quotas” that would prevent automation of certain jobs, such as daycare workers.

Governments can also bolster educational programs designed to train workers for the jobs that will most likely exist in the coming decades. In a 2016 report, the President’s Council of Economic Advisers under the Obama administration suggested that fostering the skills workers need to get jobs is the best way to prevent technology-caused unemployment. To that end, the report suggests emphasizing STEM education programs in elementary and high schools, offering two years of community college education free of charge for hard-working students, and dramatically increasing funding for job training. Expanding the number of training programs available to U.S. citizens could fill as many as 1 million jobs by 2020, David Kenny, IBM’s senior vice president for Watson, wrote in an op-ed published in Wired earlier this year.

Universal basic income (UBI), arguably a fringe concept in the U.S. for much of the last century, has also gotten a lot more attention in recent years. If automated systems replace a significant portion of the world’s workforce, those people wouldn’t be able to support themselves or their families under the current economic structure. Proponents say UBI could not only provide those newly unemployed citizens with the means to survive, but it could even benefit the economy as a whole, according to researchers at the Roosevelt Institute. The governments of Canada and Finland have already begun UBI pilot programs, while tech incubator Y Combinator plans to run a trial in two yet-unnamed parts of the United States.

History doesn’t dictate the future, of course — just because technology hasn’t disrupted the workforce doesn’t mean it won’t. And though we can’t predict exactly how technology will affect the workforce in the future, we can start getting the right policies and attitudes in place to be ready when, or if, the changes do happen.