Gene Editing In Embryos

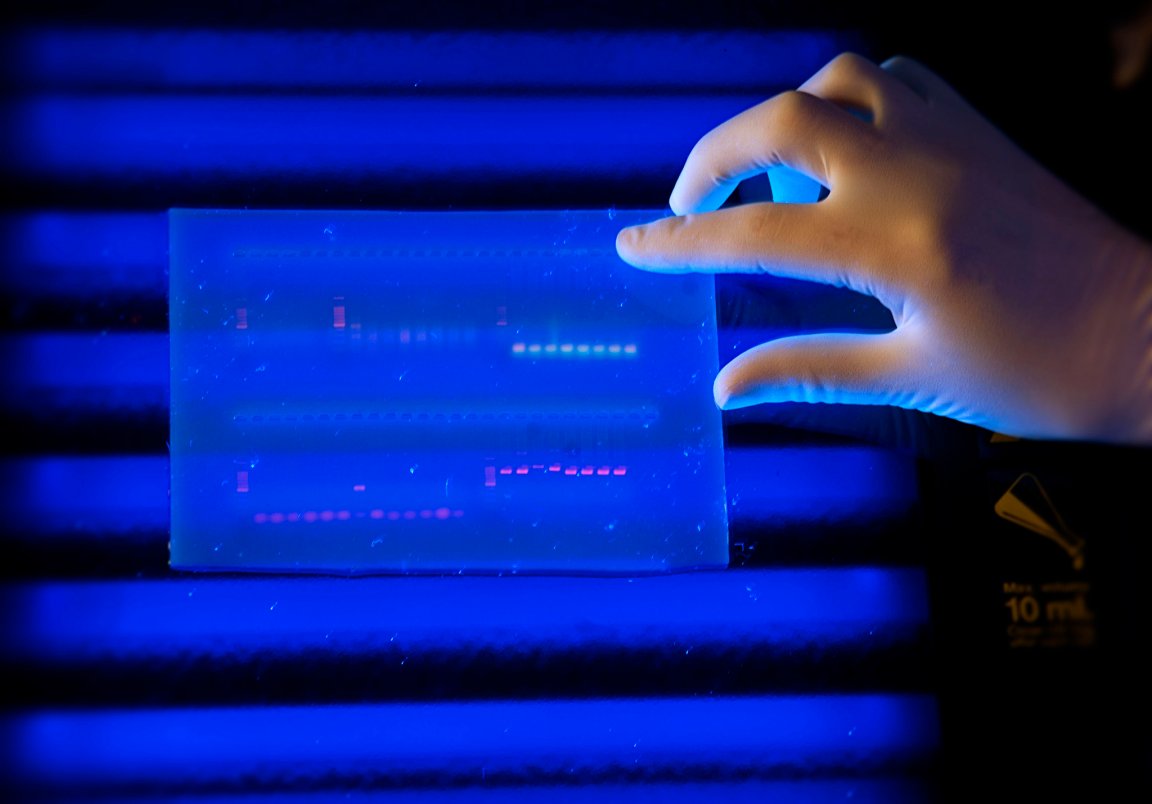

Recently, scientists achieved a world first using the genetic editing tool, CRISPR, when they corrected a genetic mutation that causes heart failure in viable human embryos. This means that certain genetic defects may be relatively simple to correct in the near future. The issue that really has people talking, though, is the fact that the same tool could potentially be used to enhance healthy embryos, altering physical traits such as appearance or mental traits like intelligence.

However, the authors of the study firmly point out that the technology’s purpose is to save lives. “This is for [the] sake of saving children from horrible diseases,” lead author Dr. Shoukhrat Mitalipov explained in a Nature podcast. With this “milestone” achieved, humanity is getting closer, Dr. George Church confirmed to The Scientist.

The work in this study solved past problems with embryo editing including the issue of mosaicism, which happens when “fixed” cells contain a mix of the new, repaired DNA and older, damaged DNA. It also conquered the issue of unintended problems in the DNA being passed down in the germline. The technique that made the difference was injecting the CRISPR setup right into the fertilized embryo or egg cell about to be fertilized. It can then be degraded after it does its work, rather than floating around on plasmids in cells where it can do damage over time.

Future Applications

This discovery is significant for anyone suffering from hereditary, genetic diseases. For people with fatal diseases such as Huntington’s, for example, carrying certain genes means they are certain to get the disease, and a 50/50 chance of passing it on. For this reason, many people with Huntington’s don’t have children. If this discovery pans out, these patients won’t have to worry about passing on a genetic disorder.

Of course the specter of the “designer baby” is always raised in this context — but the study demonstrates that the way the cells repair the genes in question, researchers can’t add anything that wasn’t already present in the DNA. In other words, repair is possible, but not adding limitless “super” traits.

Regulations And Benefits

Nevertheless, there are critical voices in the fray: former molecular biologist Dr. David King (also founder of independent genetic engineering watchdog group Human Genetics Alert) said in an editorial in The Guardian that, “In fact, the medical justification for spending millions of dollars on such research is extremely thin: it would be much better spent on developing cures for people living with those conditions.” King believes that despite medical cures being the original motivation for developing genome editing, the creation of “designer babies” for the very wealthy is inevitable — as is the deepening class stratification caused by this modern eugenic drive.

In any event, there is significant work left to be done before CRISPR could be used in clinics. Scientists want to increase its accuracy and precision, for one thing. Furthermore, IVF clinics already screen out genetic disease and other abnormalities before implanting embryos; to justify the cost of using CRISPR, it would need to show more benefits unachievable otherwise.

Either way, now is probably the time to start grappling with the ethical issues surrounding CRISPR. Waiting until it is possible to use it — and dying people are waiting for it — seems shortsighted. In any event, more dialogue and research only stands to help resolve the societal issues that remain.