Designed for Disparity?

“It’s time we provided some critical scrutiny and stopped parroting the gospel of medical progress at all costs,” writes former molecular biologist Dr. David King in a recent Guardian editorial. “…we must stop this race for the first GM baby.”

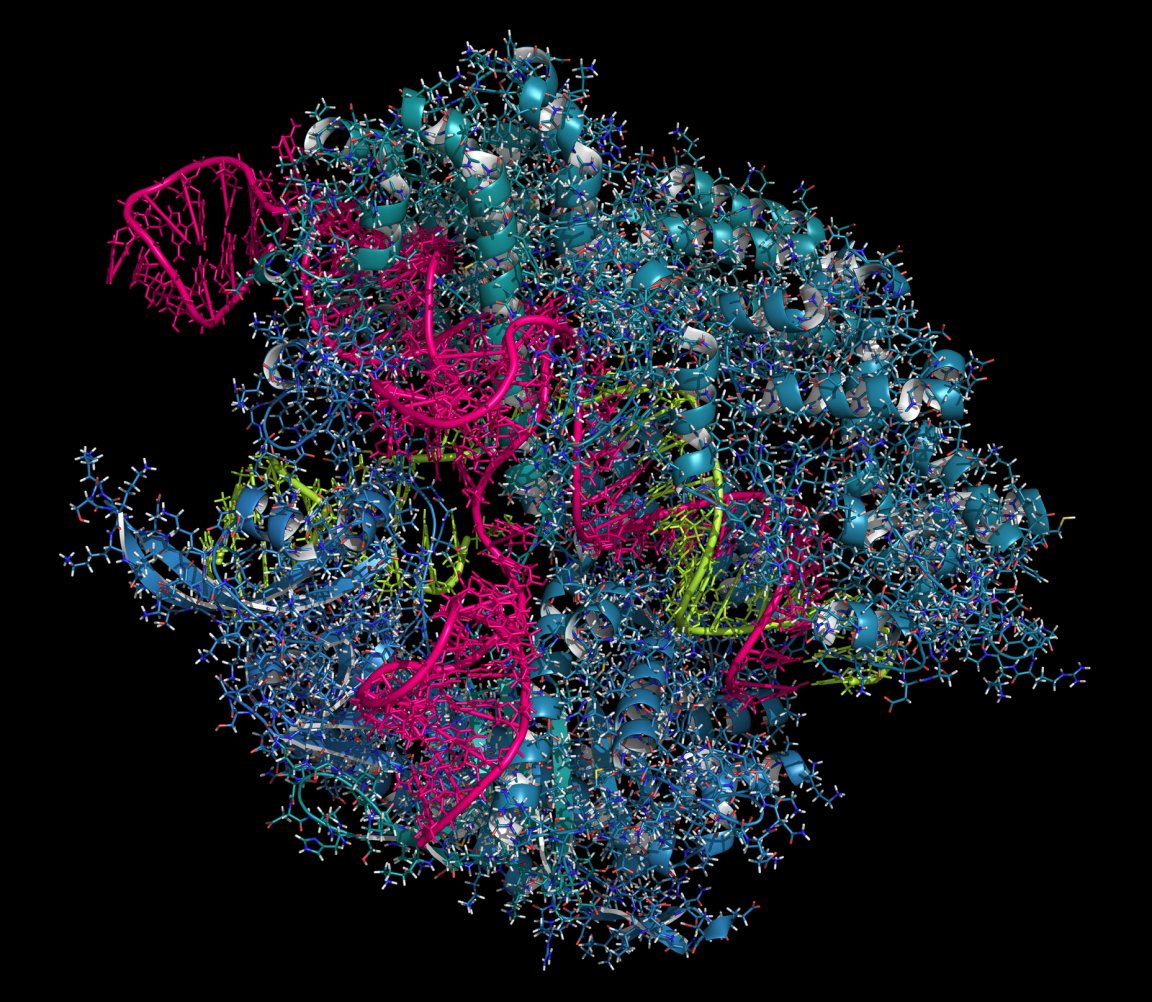

King wrote in response to the announcement earlier this month that doctors had successfully altered the genomes of single-cell human embryos. Using CRISPR, the doctors removed a gene for hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM), a common heart disease that can cause sudden cardiac arrest and death. Their results are described in Nature.

[infographic postid=”21811″][/infographic]

King is the founder of Human Genetics Alert, an independent watchdog group opposed to certain outcomes of genetic engineering. He argues that genome editing of the type in Nature is not a justified use of medical research dollars, given the ability to avoid the birth of children with such conditions through testing.

“In fact, the medical justification for spending millions of dollars on such research is extremely thin: it would be much better spent on developing cures for people living with those conditions,” King says. He argues that inevitably, even if pioneered for medical reasons, market forces will inevitably push genome editing towards creating “designer babies,” allowing the very wealthy to program desired traits into their unborn children.

King, and others, see this application as unethical and akin to eugenics.

“Once you start creating a society in which rich people’s children get biological advantages over other children, basic notions of human equality go out the window,” King writes. “Instead, what you get is social inequality written into DNA.”

Weighing the Risks

The advent of CRISPR technology has drastically accelerated the field of genetic engineering, and with it the fears of ethicists like King. Yet many say that these worries are overblown.

“We are still a long way from serious consideration of using gene editing to enhance traits in babies,” Janet Rossant, co-author of a report on human genome editing for the National Academy of Sciences (NAS), told the Guardian. “We don’t understand the genetic basis of many of the human traits that might be targets for enhancement.”

If this changes in the future, King argues that it will be impossible to keep the influence of money from directing how that knowledge is used. He bases this prediction of market-based inequality on existing practices — such as the high price tag of ova donated by “tall, beautiful Ivy League students” and the popularity of the international surrogacy market among those with the means to travel for a baby.

Yet existing regulatory systems may be enough to prevent the future King predicts.

In their report for NAS, Rossant and her co-authors emphasized that while caution and ethical oversight are necessary, the US Food and Drug Administration’s system for evaluating medical products could, too, assess potential uses of genome editing. The authors predict that editing for purposes of enhancement — as they put it, “not clearly intended to cure or combat disease and disability” — would not pass muster.

Additionally, King’s argument largely overlooks the potential of gene editing to help children whose conditions are unlikely to have a cure, or whose parents are unwilling to reject a pregnancy.

For Lee and many others suffering from genetic disease, even a selective regulatory establishment may spell collateral damage for the rest of their lives. But the fact stands: caution and oversight will be paramount when playing with the very means nature gave us for life.