Could vs Should

In 2013, some 200 million humans suffered from malaria, and an estimated 584,000 of them died, 90 percent in Africa. The vast majority of those killed were children under age 5. Decades of research have fallen short of a vaccine for this scourge. A powerful new technique that allows scientists to selectively edit entire genomes could provide a solution, but it also poses risks—and ethical questions science is only beginning to address.

The technique relies on a tool called a gene drive, something scientists have discussed since 2003 but which has only recently become possible. A gene drive greatly increases the odds that a particular gene will be inherited by all future generations. Genes occasionally evolve the ability naturally, but if we could engineer it deliberately, small interventions could have enormous impact, giving scientists the power to eradicate diseases, remove invasive species, and wholly remake the natural landscape.

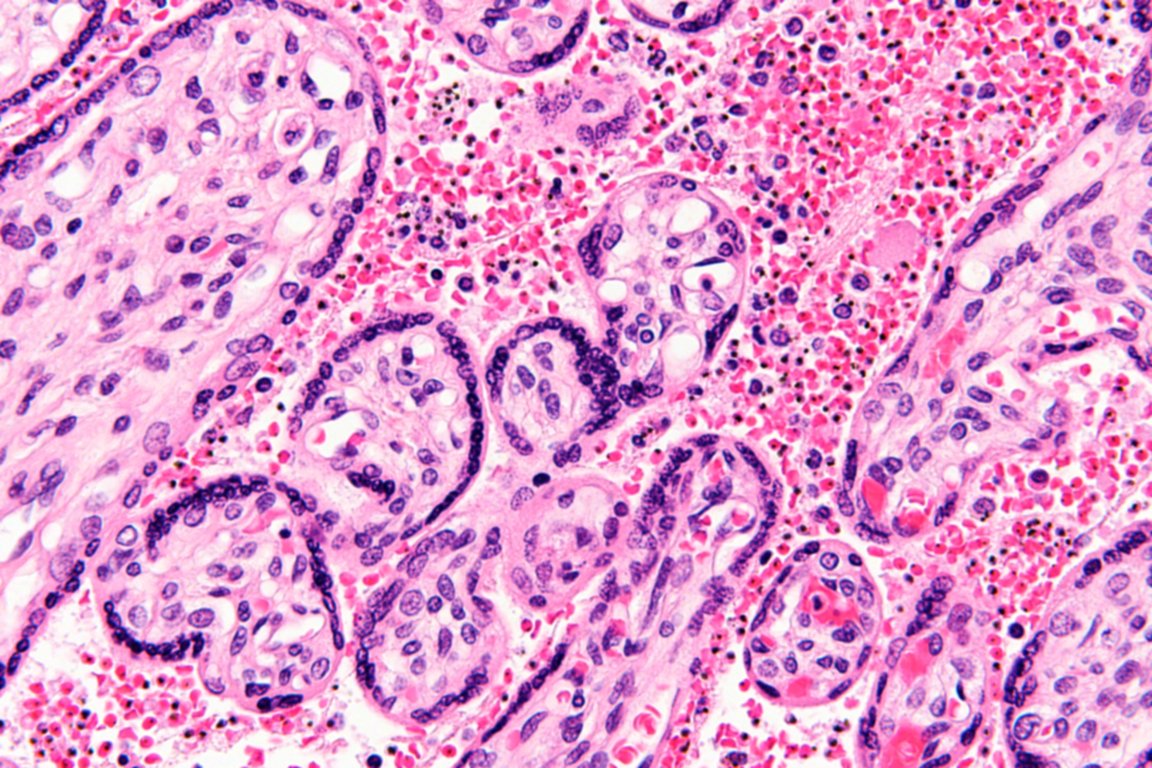

One proposed use of a gene drive would alter the genetic code of a few mosquitoes that carry the malaria parasite, ensuring that the ‘Y’ chromosome would always be passed on. The result is a male-only line that systematically topples the population’s gender balance. Once started, a carefully implemented gene drive could eradicate the entire malaria-causing Anopheles species.

“Its advantage over vaccines is that you don’t have to go out and inject every person at risk,” says George Church, a geneticist at the Wyss Institute at Harvard Medical School. “You simply have to introduce a small number of mosquitoes into the wild, and they do all the work. They become your foot soldiers, or your cadre of nurses.”

The question becomes ‘Should we?’ rather than ‘Can we?’ To what extent do scientists have the right to work on problems where, if they screw up, it could affect us all? – Kevin Esvelt

But because gene drives spread the adaptation throughout an entire population, some scientists are concerned that the technology is advancing before we have a conversation about the best ways to use it wisely – and safely.

“Of all the species that cause human suffering, the malarial mosquito is arguably number one,” says Kevin Esvelt, a researcher at the Wyss Institute. “If a gene drive would allow us to eradicate malaria the way we eradicated smallpox, that’s a possibility we at least need to consider. At the same time, this raises questions of, who gets to decide? Given the urgency of problems like malaria, we should probably be talking about it now.”

The Machinery of Gene Drives

Interest in gene drives’ potential has intensified since 2012, when scientists developed the gene-editing technique known as CRISPR (for DNA sequences called clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats). Derived from a bacterial defense strategy, CRISPR is a search, cut-and-paste system that works in any cell. It uses an enzyme to home in on a specific nucleotide sequence, slice it, and replace it with others of the scientists’ choosing. CRISPR is cheap and precise, making gene drives viable.

In normal sexual reproduction, offspring inherit a random half of genes from each parent. By encoding the CRISPR editing machinery in a genome along with whatever new trait you’d want to include, you would ensure that any offspring not only have the new mutation, but the tools to give that same trait to the next generation, and so on. The gene then drives through an entire population exponentially.

“It would be as if in your family, all of your daughters and sons insisted that all of their daughters and sons would have the same last name. Then your name would spread throughout the population,” Church says.

Mosquitoes reproduce quickly, making them an ideal target for CRISPR modification, Esvelt says. If the mutation reduced mosquitoes’ offspring or rendered males sterile, the population could be wiped out in a single season—along with the parasite that causes malaria.

This would require more work to isolate the genes involved, however. The technique also needs to become more efficient, Church says. The enzyme that hunts down target DNA sequences sometimes misses its mark, which could introduce unintended—and harmful—changes in the genome that spread throughout the species.

Genetic Upgrades or Risks

These ethical and safety concerns came into stark relief in April, when Chinese scientists reported editing the genomes of human embryos. The embryos were already non-viable, meaning they would not have resulted in live birth. CRISPR-mediated changes to their chromosomes were unsuccessful, and resulted in several off-target mutations, according to the researchers, led by Junjiu Huang at Sun Yat-sen University in Guangzhou, China. The paper set off a firestorm of controversy and calls for a moratorium on such research, including from the National Academies and the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy.

“We should be very concerned about the prospect of using these gene editing techniques for altering traits that are passed on,” says Marcy Darnovsky, executive director of the Center for Genetics and Society, a California-based nonprofit. “If you think about how that could—or perhaps would—likely play out in the social, political, and commercial environment in which we all live, it’s easy to see how you could get into hot water pretty quickly. You could have wealthy people purchasing genetic upgrades for their children, for instance. It sounds like science fiction.”

Even if gene drives are only used in pests, ethical questions still loom large. Eliminating a whole mosquito species could make way for new pests, or disrupt predators who feast on the insects, Esvelt says. And there could be human consequences, too. David Gurwitz, a neuroscientist at Tel Aviv University in Israel, wrote in an August 2014 letter to the journal Science that gene drives could also be used for nefarious purposes.

“Just as gene drives can make mosquitoes unfit for hosting and spreading the malaria parasite, they could conceivably be designed with gene drives carrying cargo for delivering lethal bacteria toxins to humans. Other scary scenarios, such as targeted attacks on major crop plants, could also be envisaged,” he wrote. He called for elements of CRISPR editing techniques to stay out of the scientific literature. In an email, he said he is “amazed at the lack of public discussion” to date on gene drive use.

Offense vs. Defense

In part because it is so inexpensive—the reagents and plasmid DNA used in CRISPR modification can be had for under $100, Church says—the method has spread through labs around the world like wildfire. “It’s hard to keep people from doing things that are simple and cheap,” he says. It has been shown to work in at least 30 organisms, according to Esvelt. As CRISPR use becomes more common, Esvelt, Church and their colleagues have aimed to develop ways to ensure its safety.

If one modified organism escapes from a lab and is able to breed with a wild relative, its altered gene would quickly spread through the entire population, making containment especially important. In April 2014, Esvelt, Church and a team of scientists published a commentary in Science suggesting methods for preventing accidental gene drive releases, such as conducting experiments on malarial mosquitoes in climates where no Anopheles relatives live. Esvelt also suggests CRISPR itself could be used to reverse an accidental release, by simply undoing the edit.

In April 2015, Church and colleagues and a separate team led by Alexis Rovner and Farren Isaccs of Yale University reported two new ways to generate modified organisms that could never survive outside a lab. Both approaches make the altered organism dependent on an unnatural amino acid they could never obtain in the wild.

Turning this concept inside out could yield engineered pests or weeds that succumb to natural substances that don’t harm anything else, Esvelt says. Instead of modifying crops to resist a broad-spectrum herbicide, for instance, gene drives could modify the weeds themselves: “You could create a vulnerability that did not previously exist to a compound that would not harm any other living thing.”

But any containment methods would have to follow the law, which remains murky, he says. Absent a national policy—which Darnovsky says should come from Congress—scientists should be talking about how, and when, CRISPR should be used.

“The question becomes ‘Should we?’ rather than ‘Can we?’” Esvelt says. “To what extent do scientists have the right to work on problems where, if they screw up, it could affect us all?”

Darnovsky, who notes that scientists have only just begun to understand the machinery of life as it evolved over millions of years, argues that scientists should not monopolize discussions about the use of CRISPR.

“We need to develop habits of mind, or habits of social interaction, that will allow for some very robust public participation on the use of these very powerful technologies,” she says. “It’s the future of life. It’s an issue that affects everybody.”