Targeting A Cancer Biomarker

This week the FDA granted approval to the cancer drug Keytruda, an immunotherapy drug. This is a milestone — the first time a cancer drug has received approval for targeting a particular biomarker rather than a location in the body.

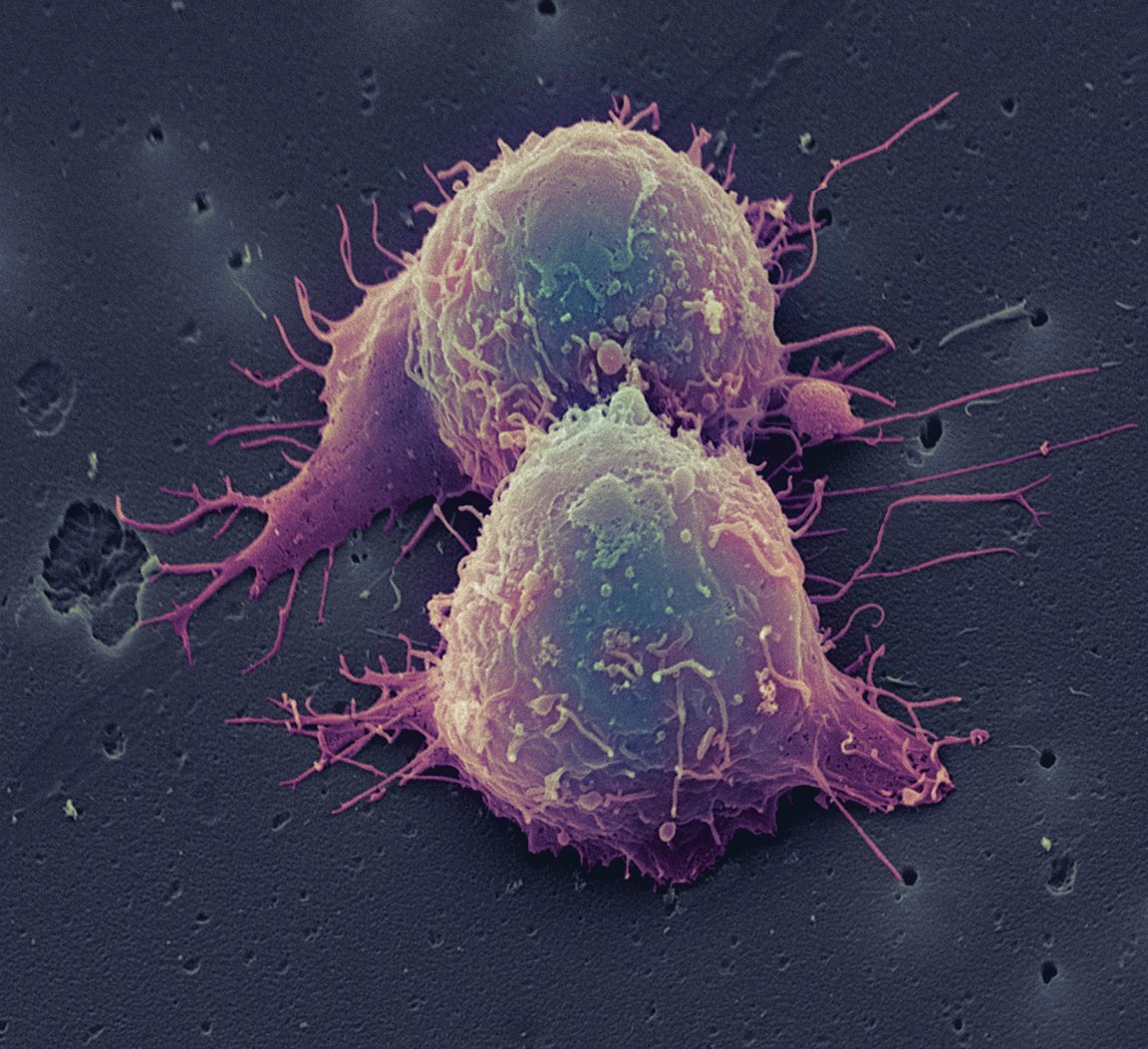

In other words, this development marks a new way of approaching cancer treatments. Now, drug developers are validated in developing new medications focused on the genetics of both patient and tumor, rather than the harsher, scorched-earth tactics of the past that kill healthy and sick cells alike, such as chemotherapies.

Keytruda (pembrolizumab) is designed for patients who have mutations and other genetic flaws in their “mismatch repair” genes that prevent their cells from being able to fix DNA errors. This particular genetic difference can mean higher susceptibility to cancer, but it also means receptivity to Keytruda. The drug can be used to excite the immune system of anyone with the genetic biomarker to attack solid tumors.

This kind of treatment was first approved for use against advanced skin cancer in 2014, and none too soon. This was the type of checkpoint inhibitor drug that saved former U.S. President Jimmy Carter’s life.

Finding the Right Treatment

Unfortunately, immunotherapy appears not to benefit all patients, and experts are not sure why. So far, only about one in 12 seem to benefit from immunotherapy. Clinical trials are ongoing, but not all researchers are sure that they are able to select the right patients to show the effectiveness of the drugs. Nevertheless, as more is understood about how checkpoints and biomarkers work, researchers hope to incrementally improve the effectiveness of immunotherapies.

But immunotherapy isn’t the only front for battling cancer. Early detection is another critical priority, and a recent breakthrough in the form of a simple blood test has made lung cancer detectable with 92 percent accuracy. Researchers have also developed a way to detect esophageal cancer using a sponge on a string.

Prevention is also on the medical agenda. Researchers have also discovered how to use CRISPR to target the “command center” of cancer in mice; this technique has been proven to shrink aggressive tumors in mice, who survived at an astonishing rate of 100 percent. Scientists have also been working to create a personalized cancer vaccine.

While there’s not yet any one best way to prevent, detect, or treat cancer, it’s safe to say that genomics will continue to play a role in the best practices for fighting the disease. The change in focus away from the location of tumors and toward underlying genetics is absolutely essential to success.