A Formidable Opponent

Even with all the advances in medicine eliminating old and emerging diseases, treating or vaccinating them out of existence, one malady has been surprisingly resistant: cancer. Despite the millions of dollars poured into cancer research, current options for treatment are sometimes just as bitter as the disease itself.

While traditional treatments like chemotherapy and radiation are commonly known, they take a serious toll on the patient. Both work by targeting and killing the cancer cells directly, and while the processes have yielded positive results for some patients, the treatments involve nasty chemicals and procedures that sometimes end up causing infertility, heart damage, or even secondary cancers.

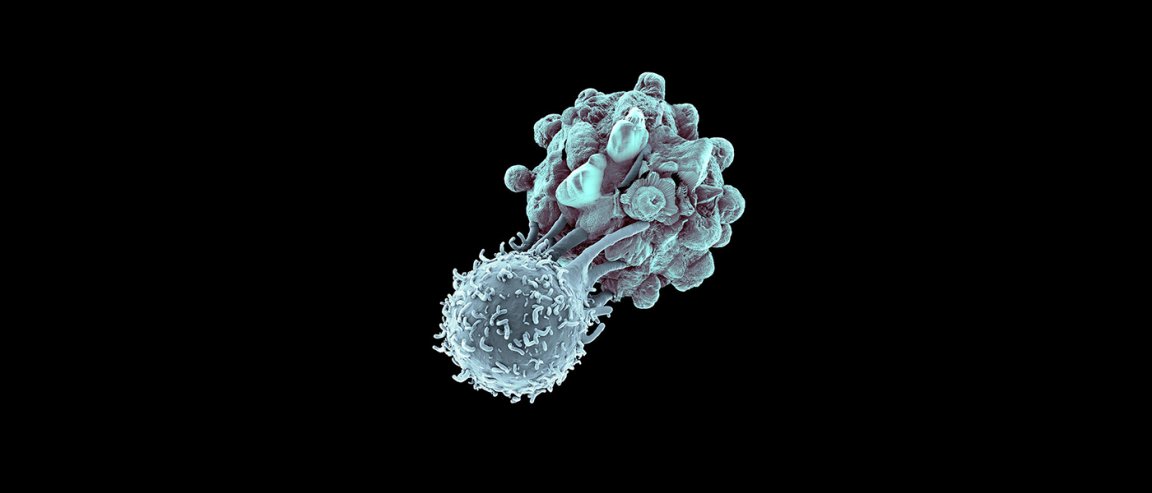

But one cancer treatment takes a very different approach: immunotherapy. Cancer is know for being crafty in evading the standard immune response to other diseases, so immunotherapy works to empower the immune system to target the cancer like it would other harmful cells. Does this mean immunotherapy could be the key to curing cancer?

Beefing up defenses

Immunotherapy can be administered in many ways. Cancer vaccines can be used to prevent the disease in healthy people as well as treat it in those already afflicted, while monoclonal antibodies can bind to cancer cells and then cause an immune response to destroy those cells. Our bodies’ cells already make cytokines, and because they play an important role in our reaction to cancer, those proteins can be used as an immunotherapy treatment option as well.

In addition to the above, two immunotherapy treatments that are garnering quite a bit of attention in particular are CAR T-cell therapy and checkpoint inhibitor therapies.

CAR T-cell therapy works by having the patient’s T-cells genetically modified to target the specific cancer from which they are suffering. Though the research is still in its experimental phase, researchers have recruited popular gene-editing technique CRISPR to move it along. The other therapy, checkpoint inhibitors, is a bit more advanced. It removes the “masking” that cancer cells use to hide from the immune system, and four checkpoint inhibitors (Yervoy, Keytruda, Opdivo, and Tecentriq) are already cleared by the FDA.

While immunotherapy is promising, it’s not without its drawbacks, the main of which is that it has rather low response rates. Oncologist Elizabeth Jaffee told the Washington Post that checkpoint inhibitors just have an average response rate of 20 percent. The therapies also come with a slew of potential side effects, which range from the rather benign (almost all of those treated experience flu-like symptoms) to the more serious (brain swelling, organ damage). They are also very expensive, with estimated costs in the hundreds of thousands per year per patient.

Research is already underway to improve the response rate of immunotherapy, and at the center of these efforts is establishing a way to determine the correct combination of immunotherapy treatments for the specific individual. Treatments for HIV and AIDS became increasingly more effective when doctors realized they needed to use the right cocktail of treatments, so cancer patients are being examined up to the genetic level to determine the proper combination of treatments.

In the United States alone, more than half a million people are expected to die from cancer this year, so any treatment, immunotherapy or otherwise, is worth exploring if it has the potential to save some of those lives.