Preemptive Strike

Each year, the world invests billions of dollars into cancer research, but because cancer cells multiply rapidly and without limit, developing effective treatments for the disease is extremely difficult. Now, a new study published in the journal Cell Stem Cell may reveal a way we could create a cancer vaccine, essentially training our bodies to fight the disease before it even takes hold.

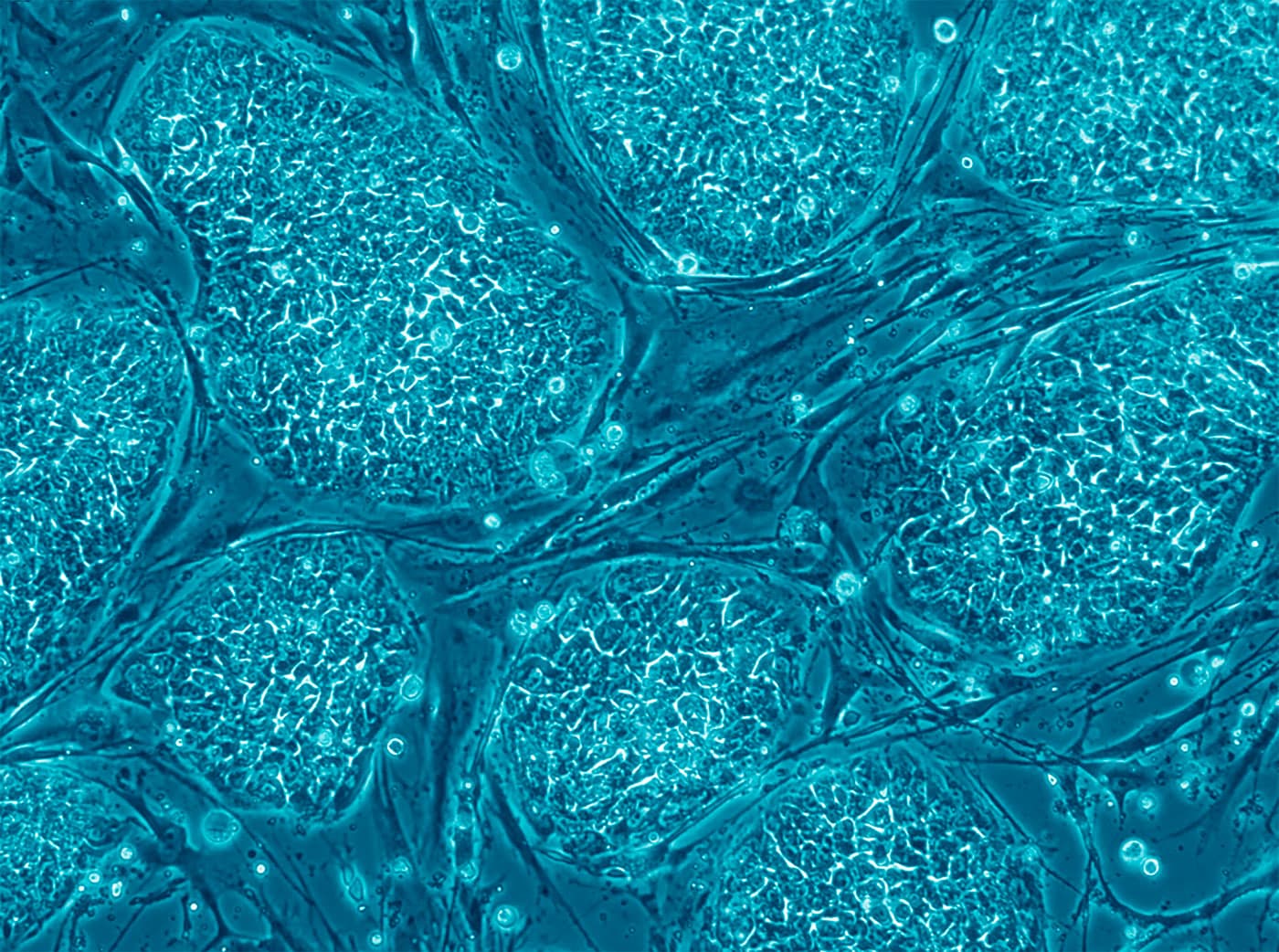

Instead of a generalized treatment, researchers from the Stanford University School of Medicine propose using induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells to train the immune system to attack tumors or even prevent them from forming.

Like cancer cells, iPS cells can propagate indefinitely. They can be coaxed to assume many different kinds of cells, making them the perfect ingredient in regenerative medicine, and best of all, they can be generated from adult stem cells.

For their study, the researchers experimented with four groups of mice, each injected with a specific vaccine containing modified iPS cell once a week for a month. One group was given genetically matching iPS cells that had been irradiated to prevent the growth of teratomas — a kind of tumor containing various cell types. Another group received adjuvant, a generic immune-stimulating agent, while a third got a combination of irradiated iPS cells and adjuvant. The fourth group served as a control.

After four weeks, the researchers injected the mice with a mouse breast cancer cell line. In all four groups, the mice developed breast cancer tumor cells after a week. However, in seven of the 10 mice that received the iPS and adjuvant combination, the tumors shrank. Furthermore, two of the mice that got the iPS and adjuvant combo totally rejected the tumor cells, surviving for more than a year after transplantation. The researchers also managed to record similar results when tested on mouse melanoma and a type of lung cancer called mesothelioma.

"We've learned that iPS cells are very similar on their surface to tumor cells," Joseph Wu, the director of Stanford's Cardiovascular Institute, said in a press release. "When we immunized an animal with genetically matching iPS cells, the immune system could be primed to reject the development of tumors in the future. Pending replication in humans, our findings indicate these cells may one day serve as a true patient-specific cancer vaccine."

A New Line of Defense

This is hardly is the first proposal to create a cancer vaccine, but as lead author Nigel Kooreman explained in the press release, the group's approach is powerful as it would expose the patient's immune system to a variety of cancer-specific epitopes in one go. "Once activated, the immune system is on alert to target cancers as they develop throughout the body," he said.

Another study currently being prepped for human trials also stimulates the immune system to fight different kinds of cancer, but the iPS approach from Stanford presents a more personalized treatment. Each particular vaccine of iPS cells must be taken from the respective patients.

"Although much research remains to be done, the concept itself is pretty simple," said Wu. "We would take your blood, make iPS cells, and then inject the cells to prevent future cancers. I'm very excited about the future possibilities."

Kooreman and his colleagues still need to test this method using human cancer and immune cells in a lab setting, but if effective, it could present a new line of defense in the ongoing battle against cancer.

Share This Article