Over the last decade or so, scientists have learned that the Earth is more complex than we ever imagined. There is an underground “ocean” tucked deep within Earth’s interior, life all the way at the bottom of the deepest oceanic abyss, large and mysterious holes that pop up out of nowhere, and a number of other things (the list goes on and on, really). As fascinating as all of these geological things are, what we can’t see might be even better

Now, a team of researchers from the University of Colorado, Boulder have added another new thing to the list. In addition to the magnetic portals connecting Earth to the Sun, the huge bubble of dead star guts (which technically encompasses our entire solar system), and a (theoretical) halo of dark matter, Earth also appears to be surrounded by an invisible dome (*cue creepy music*), extending well over 7,200 miles above Earth’s surface.

Like our atmosphere and magnetic field, this newly-discovered ‘structure’ strategically shields Earth from dangerous particles, including “killer electrons” that whip around the planet at relativistic speeds (or speeds comparable to that of light). Despite the fact that WE are protected from them, it’s well known that they pose serious danger to astronauts and other space-based equipment.

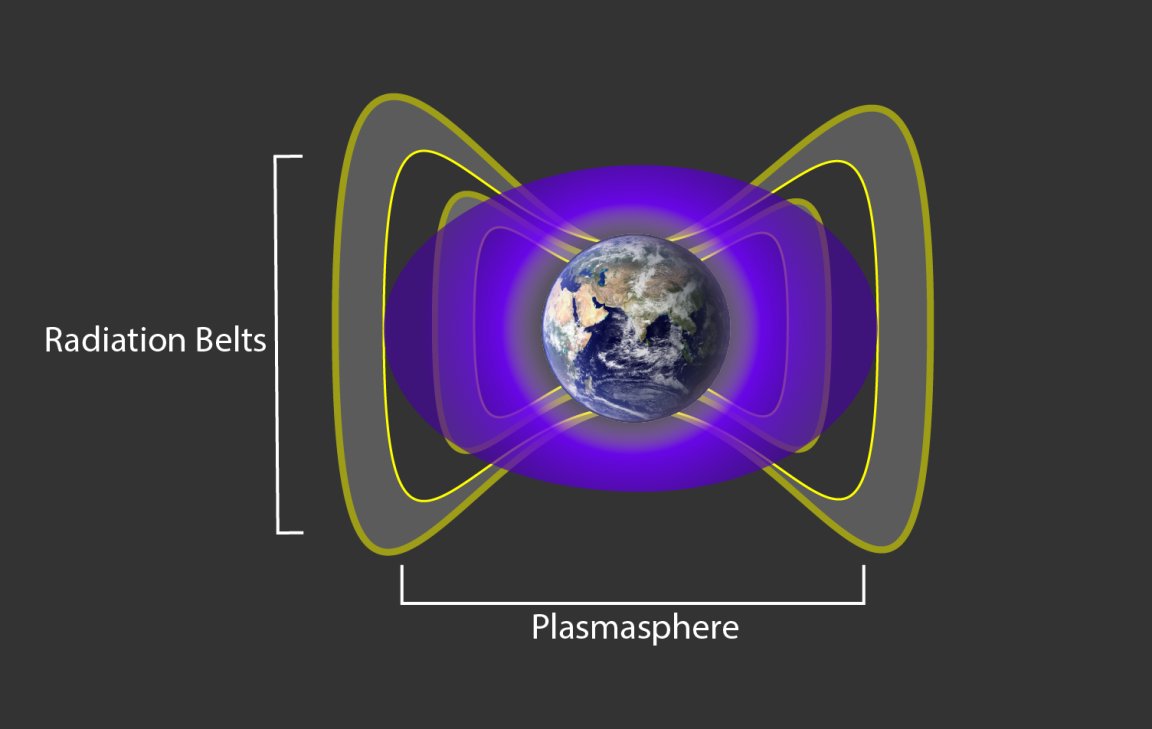

It’s also believed that the barrier is tied to the Van Allen belts — the two, doughnut-shaped rings of high-energy radiation encircling Earth.

As Professor Daniel Baker, director of CU-Boulder’s Laboratory for Atmospheric and Space Physics (LASP), describes, “The barrier to the particle motion was discovered in the Van Allen radiation belts.” “Held in place by Earth’s magnetic field,” they “periodically swell and shrink in response to incoming energy disturbances from the Sun.”

“As the first significant discovery of the space age, the Van Allen radiation belts were detected in 1958 by Professor James Van Allen and his team at the University of Iowa and were found to be comprised of an inner and outer belt extending up to 25,000 miles above Earth’s surface. In 2013, Baker — who received his doctorate under Van Allen — led a team that used the twin Van Allen probes launched by NASA in 2012 to discover a third, transient “storage ring” between the inner and outer Van Allen radiation belts that seems to come and go with the intensity of space weather.”

“The latest mystery revolves around an “extremely sharp” boundary at the inner edge of the outer belt at roughly 7,200 miles in altitude that appears to block the ultrafast electrons from breeching the shield and moving deeper towards Earth’s atmosphere.”

“It’s almost like theses electrons are running into a glass wall in space,” said Baker, the study’s lead author. “Somewhat like the shields created by force fields on Star Trek that were used to repel alien weapons, we are seeing an invisible shield blocking these electrons. It’s an extremely puzzling phenomenon.”

[via: University of Colorado Boulder]

When the researchers first found the dome, they believed that the charged electrons in question loop back around Earth at 100,000 miles per second, before diverting downward (into the upper-atmosphere). From there, they meet air molecules, which eventually results in them being wiped out completely. However, they now know that “the impenetrable barrier seen by the twin Van Allen belt spacecraft stops the electrons before they get that far,” said Baker.

The group looked at a number of scenarios that could create and maintain such a barrier. The team wondered if it might have to do with Earth’s magnetic field lines, which trap and control protons and electrons, bouncing them between Earth’s poles like beads on a string. The also looked at whether radio signals from human transmitters on Earth could be scattering the charged electrons at the barrier, preventing their downward motion. Neither explanation held scientific water, Baker said.

“Nature abhors strong gradients and generally finds ways to smooth them out, so we would expect some of the relativistic electrons to move inward and some outward,” said Baker. “It’s not obvious how the slow, gradual processes that should be involved in motion of these particles can conspire to create such a sharp, persistent boundary at this location in space.”

Another scenario is that the giant cloud of cold, electrically charged gas called the plasmasphere, which begins about 600 miles above Earth and stretches thousands of miles into the outer Van Allen belt, is scattering the electrons at the boundary with low frequency, electromagnetic waves that create a plasmaspheric “hiss,” said Baker. The hiss sounds like white noise when played over a speaker, he said.

[via: University of Colorado Boulder]

Baker finishes by remarking that the researchers still believe the ‘plasmaspheric hiss’ is related to the barrier, but it’s not the be all, end all mechanism at work,

“I think the key here is to keep observing the region in exquisite detail, which we can do because of the powerful instruments on the Van Allen probes. If the Sun really blasts the Earth’s magnetosphere with a coronal mass ejection (CME), I suspect it will breach the shield for a period of time,” said Baker, also a faculty member in the astrophysical and planetary sciences department.

“It’s like looking at the phenomenon with new eyes, with a new set of instrumentation, which give us the detail to say, ‘Yes, there is this hard, fast boundary,'” said John Foster, associate director of MIT’s Haystack Observatory and a study co-author.