If you followed news about either the media industry or space exploration back in 2021, you probably remember when the New York Times accidentally published a story claiming that watermelons had been found on the planet Mars.

“Authorities say rise of fruit aliens is to blame for glut of outer space watermelons,” read the story, which the newspaper deleted less than an hour later, but is still accessible in an archived snapshot. “The FBI declined to comment on reports of watermelons raining down, but confirmed that kiwis have been intercepted.”

Unsurprisingly, a spokesperson for the paper soon clarified that the article had been a dummy draft that had been inadvertently published as part of a testing system.

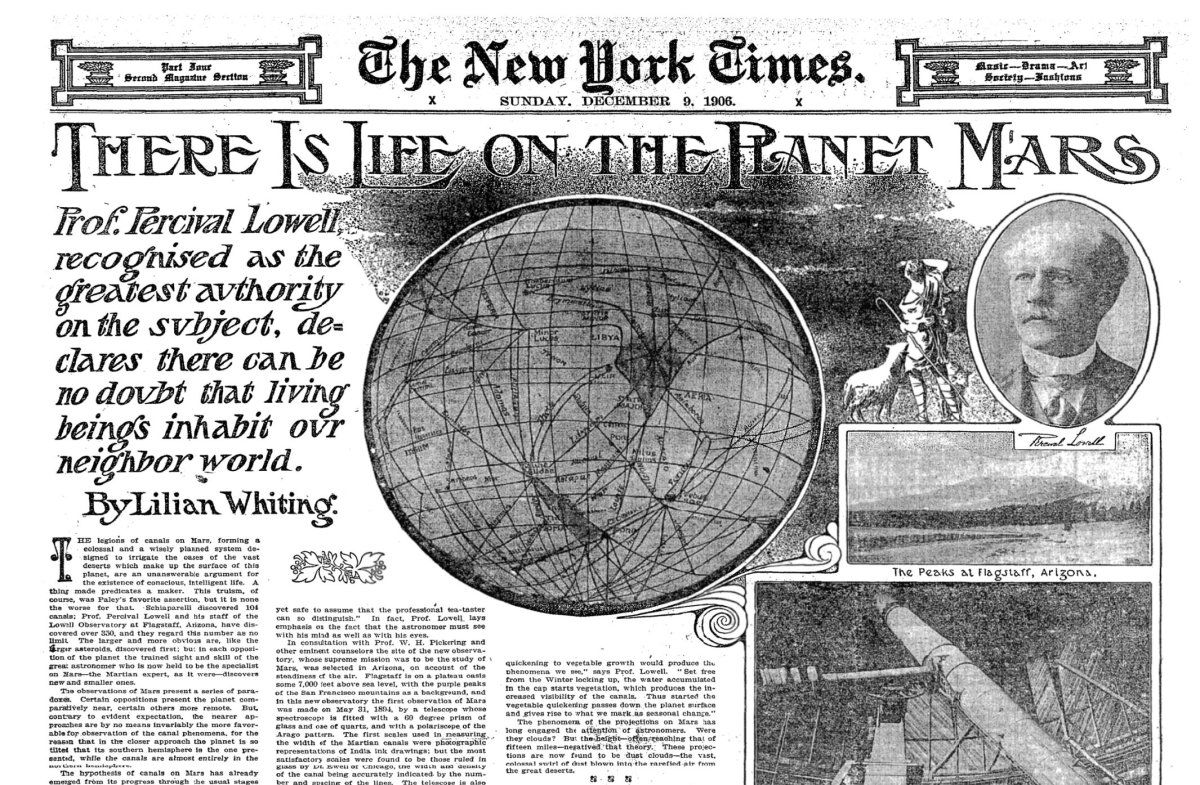

As it turns out, it wasn’t even the first time that the paper of record had mistakenly claimed that life had been discovered on the Red Planet. That distinction goes to an extraordinary feature published in December 1906, which the New York Times ran under the screaming all-caps headline of “THERE IS LIFE ON THE PLANET MARS.”

In the story, journalist Lilian Whiting — a reporter and poet so prominent at the time that she still has her own Wikipedia page a full 78 years after her death — wrote breathlessly of Percival Lowell, a controversial astronomer who founded the Lowell Observatory in Arizona, which later went on to discover the planet Pluto.

Lowell was convinced that using the large telescope he’d constructed at his observatory in Flagstaff, he had glimpsed “legions of canals on Mars, forming a colossal and a wisely planned system designed to irrigate the oases of the vast deserts which make up the surface of this planet.”

“The astronomer finds a network of marvelously designed canals traversing the deserts, meeting at certain points, the lines uniform, thousands of miles in length, three to seventeen canals sometimes converging at one point,” Whiting wrote. “Therefore, the only logical result that can be reached… is that the oases are great centres of population; that the canals are constructed by guiding intelligence for the purposes as set forth above, and that their existence is an unanswerable and an absolute proof that there is conscious, intelligent, organic life on Mars.”

The whole article is worth a read. In addition to a fascinating series of delightfully old-timey stylistic choices and typos, it’s a mesmerizing snapshot of a moment when science seemed to feel vast and unknown, when an eccentric professor could make outrageous extrapolations about something he thought he’d spied in his telescope and get the whole thing written up in one of the world’s most influential newspapers.

To be clear, Lowell’s claims attracted plenty of controversy at the time from his peers; after seeing Lowell’s astronomical sketches at a meeting of the Royal Astronomical Society, one critic wrote that “I do not know whether Mr. Lowell has been looking at Mars until he has got Mars on the brain, and by some transference transcribed the markings to Venus.”

The whole episode is back in the public view because of a new book by the journalist David Baron, titled “The Martians.” In it, Baron explores the explosion of interest — and wonderfully wild-eyed pseudoscience — around the planet Mars during the Gilded Age. Scientific luminaries including Nikola Tesla and Alexander Graham Bell jumped on the trend, before a scientific backlash tore the whole thing down.

In a full-circle moment, Baron’s book got a glowing review this week — published in the New York Times.

Mars fever “suffused polite society in America, with vivid depictions of aliens appearing in soap and liquor ads, on Broadway and at dinner parties,” reads the paper’s writeup of the book. And in a meta twist, the “vigorous yellow press, and eventually even more sober outlets like the New York Times and the Wall Street Journal, published all kinds of speculation about the Red Planet as fact.”

More on Mars: Scientists Reveal Easy Three-Step Plan to Terraform Mars