The Dawn of the Quantum Age

By now, most readers of Futurism are probably pretty well acquainted with the concept (and fantastic promise) of quantum computing.

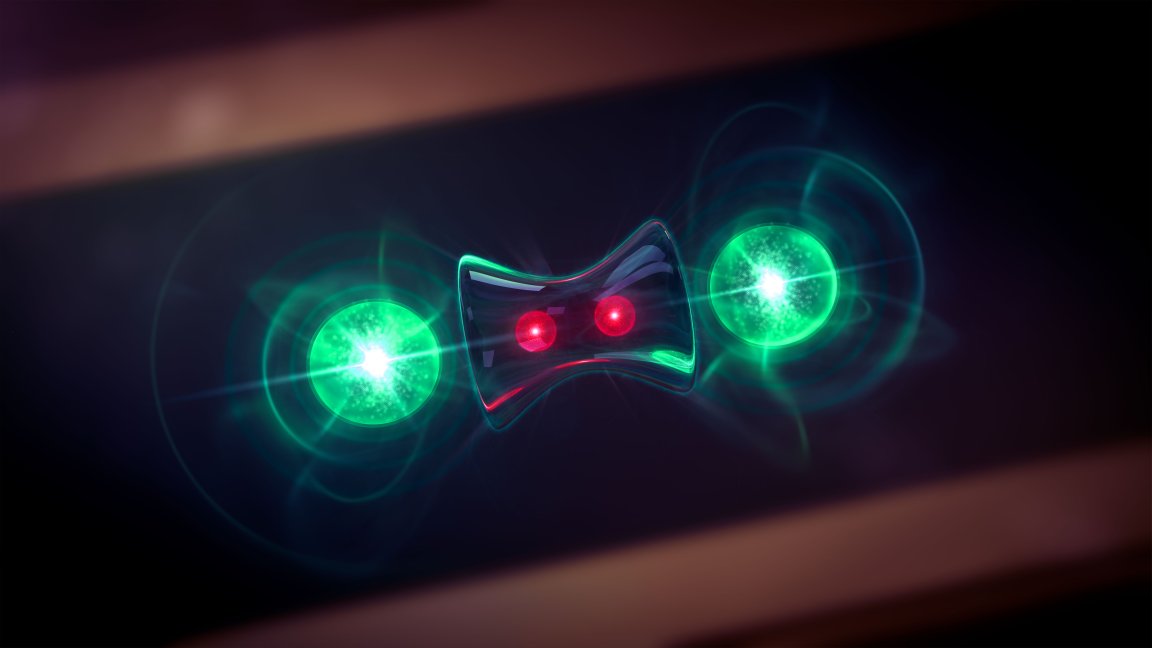

For those who aren’t, the idea is fairly (!) simple: Quantum computers exploit three very unusual features that operate at the quantum scale—that electrons can be both particles and waves, that objects can be in many places at once, and they can maintain an instantaneous connection even when separated by vast distances (a property called “entanglement”).

And whereas classical computing utilizes binary bits (ones and zeroes) to encode information, quantum computing uses “qubits”—quantum bits that can be both one and zero. Or probably one but maybe zero. Or a fifty-fifty chance of being one and zero. You get the point.

Now, this unusual property, together with entanglement, enables a quantum computer to achieve unprecedented parallel processing power, and that means performing calculations and solving problems that classical computers couldn’t even begin to fathom.

But there’s a catch: Building a large-scale quantum computer has proven to be extraordinarily difficult. It’s relatively simple to construct processors of a few qubits at most; but scaling up to something as big as today’s largest supercomputers means sacrificing those very quantum properties you were aiming for in the first place.

Now, in a study published in Nature Communications, researchers from the University of Bristol and the University of Western Australia have demonstrated that even primitive quantum processors of only a few qubits can perform important computations.

The “Quantum Walk”

Using a simple quantum circuit, constructed on a 2-qubit photonics quantum processor, the researchers were able to outperform classical computers in certain highly specialized problems.

“An exciting outcome of our work is that we may have found a new example of quantum walk physics that we can observe with a primitive quantum computer, that otherwise a classical computer could not see,” said Dr. Jonathan Matthews of the Centre for Quantum Photonics. “These otherwise hidden properties have practical use, perhaps in helping to design more sophisticated quantum computers.”

The “quantum walk” is a quantum mechanical version of such things as Brownian motion, which describes the movement of particles in a suspension, and the “drunken sailor’s random walk” i.e., all the possible directions that a staggering inebriate could turn, and thus the many different ways he could get from point A to point B. In other words, the simple quantum processor excels in calculating randomness, which is not particularly surprising, considering just how random the quantum world is.

So the new research will help design new quantum algorithms, and perhaps shed some light on how to construct larger quantum computers. For example, a promising way to circumvent the “scaling-up” problem is to rethink the whole problem—rather than building huge machines, as in classical computing, the solution may be to simply slave together a vast array of smaller quantum processors, which still maintain the required quantum effects.

In the meantime, even these little 2-qubit machines are performing useful work.

“It’s like the particle can explore space in parallel. This parallelism is key to quantum algorithms, based on quantum walks that search huge databases more efficiently than we can currently,” explains Xiaogang Qiang, a Bristol PhD student who worked on the experiment.