Your Unique Brain

Beyond its usage in criminal science, the advent of fingerprinting has done a lot to help us understand the human body’s development. The same thing is poised to happen on a much more intricate level as researchers have now found a way to “fingerprint” the brain.

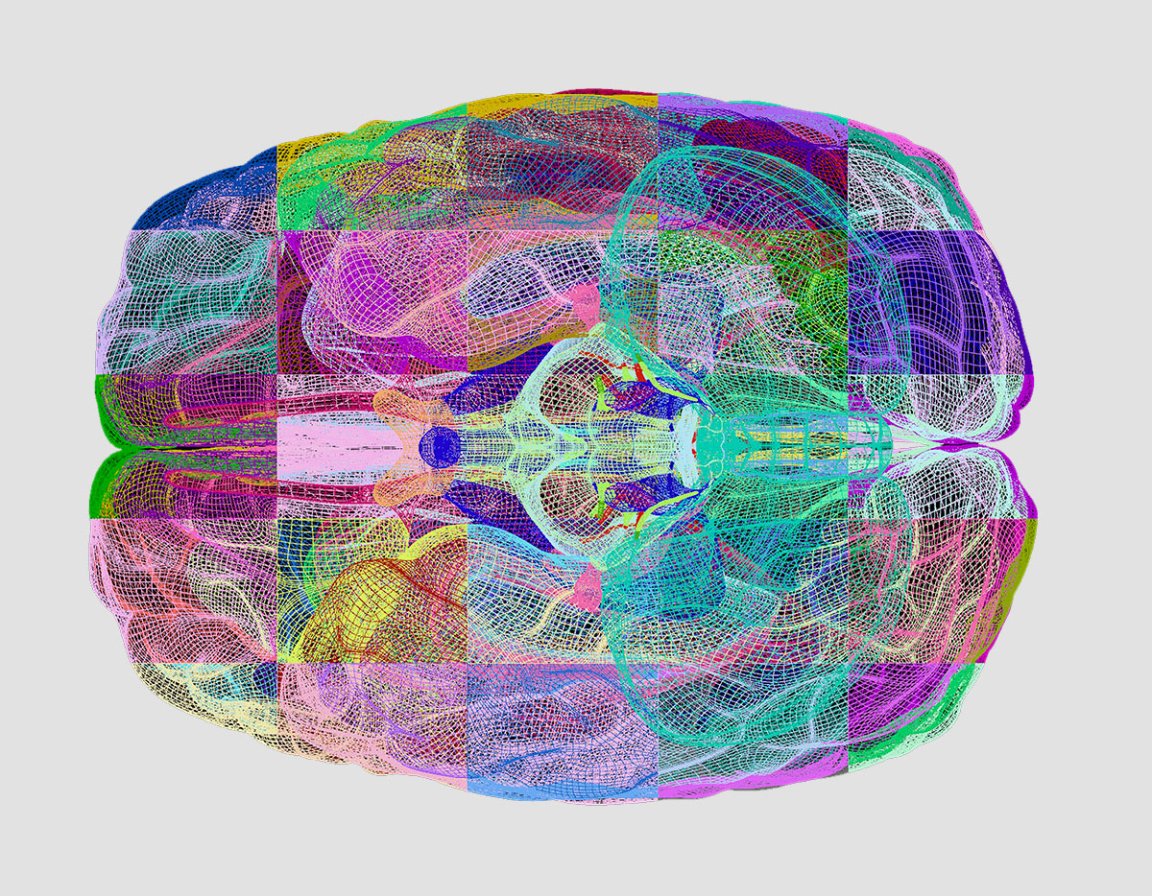

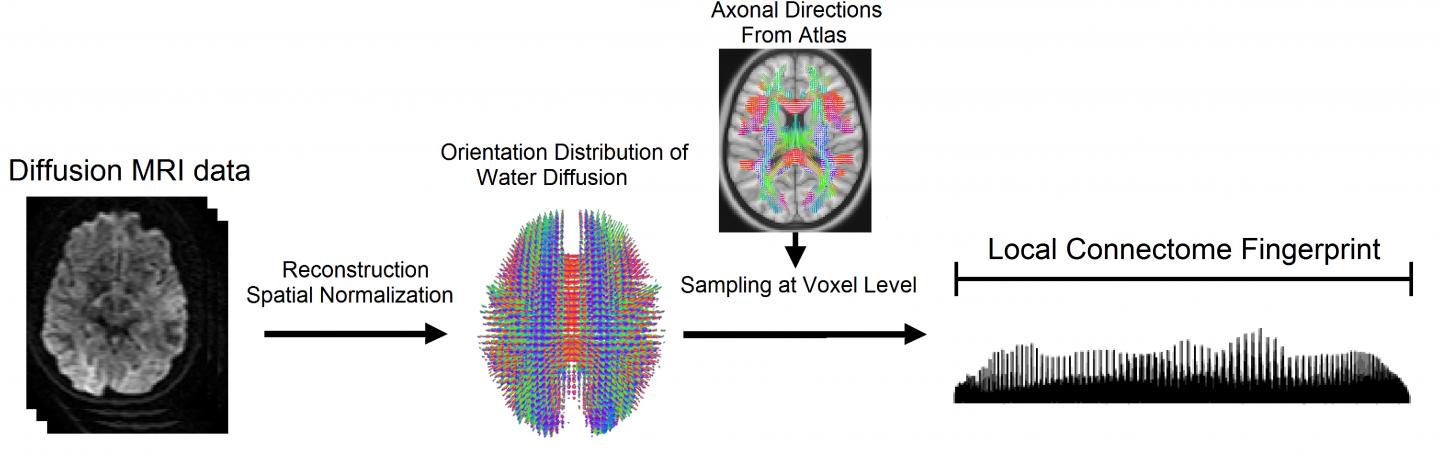

It has long been suspected that structural connections in the brain are unique to an individual. To test this theory, a team from Carnegie Mellon University studied the wiring of the brain using a method called diffusion MRI, a non-invasive approach that provides a much more detailed picture of the brain’s connections than was previously possible. The team measured and mapped the local connectomes (the point-by-point connections between white matter pathways) of 699 people using the technique and then measured the stretch of these connections to create the individual’s brain fingerprint.

To test the uniqueness of these fingerprints, they ran more than 17,000 identification tests and were able to determine whether a local connectome sample came from the same individual or not with almost 100 percent accuracy. “In a way, we are showing what neuroscience has always assumed to be true but not yet shown: We are our own unique neural snowflake,” Dr. Timothy Verstynen told the Huffington Post.

More than ID

While the cost of the technique prohibits it from being a forensic tool in identifying people, it has far more important potential uses. The team at Carnegie Mellon discovered that the connections they mapped reflected not only nature, but also nurture — a person’s experiences had an impact on their brain fingerprint. Someone born into poverty or with a lifetime of disease had those experiences reflected in their brain.

Using this mapping technique, we can see and study how each experience shapes the brain and gain insight into brain plasticity. We can also apply it to existing data, so researchers can glean new insights into previously unexplored brains. One day, the study could be used to determine susceptibility to disease, even before said disease manifests symptoms. Physiological or even psychiatric illnesses could be prevented. Coupled with advances in genome reading, we could effectively combat diseases decades before they manifest.