In the United States, 115 people die as the result of an opioid drug overdose every day. This statistic, gathered as part of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) work to understand and combat the current epidemic of opioid drug abuse in America is even more startling when you compare it to figures from the last twenty years or so. In 2016, the number of deaths attributed to an overdose of a drug like heroin or prescription opioid painkillers was five times what it was in 1999.

One of the driving forces behind this epidemic has already been determined: medical professionals over-prescribing opioid painkillers, such as oxycodone, to patients, a practice that is not only completely legal but increasingly common. Many people begin taking the drug legally but become dependent on it. When the prescription runs out and they are no longer able to get it filled, they may try to obtain it illegally. They may be motivated to buy or steal medication to help combat their pain. Some patients end up taking illegal street drugs, like heroin, in an attempt to treat the withdrawals from the opioid medications they were initially prescribed.

Drug addiction is extremely difficult to treat. Addictions that begin as the result of taking legally-prescribed medication, often as a treatment for severe or chronic pain, are even more so. That’s one reason that researchers have been trying to find entirely new avenues for treating drug addiction.

A team of researchers at The Scripps Research Institute recently published their work on the development of a potential vaccine to treat heroin addiction. The idea behind it is fairly intuitive, and in fact, the basic concept has been known to researchers since at least the 1970s.

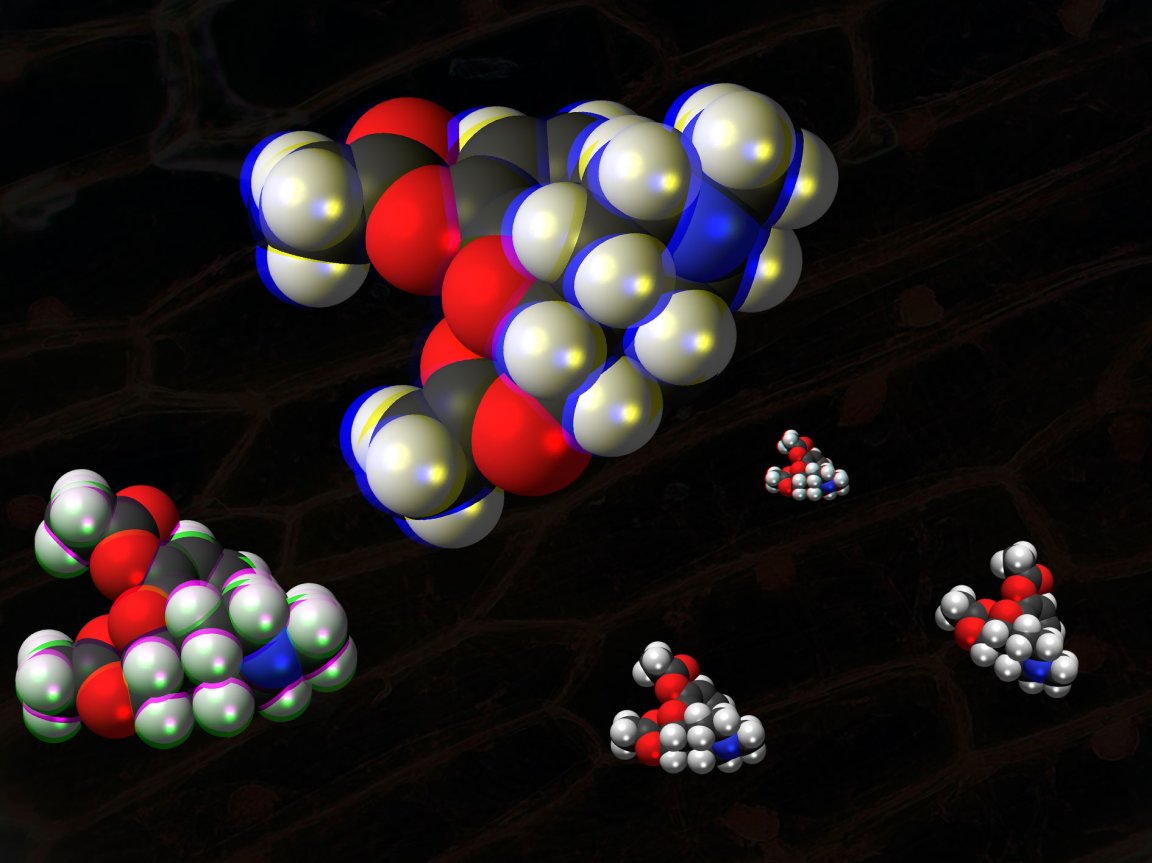

Like any immunization, an “antiheroin” vaccine would cause a person’s body to create the antibodies that bind to heroin in the blood. Then, it would prevent the drug from crossing the blood-brain barrier, which is what gives the user a high. The theory being that if the drug user no longer felt the effect of the drug, it would be far less likely that they’d relapse.

Other research teams are working on similar vaccines that could be used to treat people addicted to cocaine, or even as a potential treatment for cigarette smokers who are addicted to nicotine. Whether prescription opioid painkillers, heroin, cocaine, fentanyl, nicotine, or even alcohol, the need for new, innovative, ways to address addiction is severe. Given the sheer number of people addicted and dying each year as a result and the distressing lack of available options for treatment, the need for drastic intervention is clear.

“We’re looking for everything and anything,” R. Corey Waller, a practicing addiction specialist and chair of the legislative advocacy committee of the American Society of Addiction Medicine told Chemical and Engineering News “We don’t care if it’s voodoo, unicorns, or rainbows; we’ll take it.”

At present, the biggest challenge is finding the scientific magic that would allow these treatments to work in humans. While they have proven effective in lab animals, the results of the few human clinical trials to date have been disappointing. That was over a decade ago, though, and the failure of those trials gave researchers valuable insight into what needed to be revamped.

It’s only a matter of time before they’ll be able to try again, but those who specialize in substance abuse treatment remain cautiously optimistic. They know, perhaps better than anyone else other than the addicts themselves, just how hard it is to treat drug addiction. “The vaccines seem very promising, and they’re novel, providing a different mechanism to prevent substance abuse,” Kelly E. Dunn, Associate Professor of Psychiatry and Behavior Science at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine told Chemical and Engineering News. “But there is still a lot of work to do.”