World and Anti-World

Antimatter is not just the fictional fuel of the starship Enterprise and its journeys on Star Trek; quite the contrary, antimatter is something that scientists are currently utilizing. In fact, antihydrogen was created in 1995 (although it didn’t last long).

To many people, antimatter probably sounds a lot stranger than it really is. In it’s most basic sense, antimatter is just matter with its electrical charge reversed. In this respect, antielectrons, called “positrons,” are like an electron but with a positive charge. Along the same lines, antiprotons are like protons but with a negative charge.

However, although the definition sounds rather standard, antimatter behaves very strangely. At least, it does when it interacts with matter. Upon meeting, matter and antimatter annihilate one another in a flash of energy, leaving behind other subatomic particles. This process results in an explosion that emits pure radiation traveling at the speed of light.

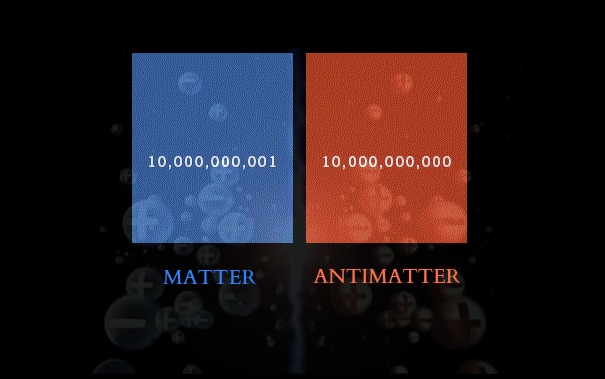

The Big Bang should have created antimatter and matter in equal amounts. If that had been so, everything would have been destroyed in, well, a bigger bang. As far as scientists know, there must have been one extra matter particle for every billion matter-antimatter pairs. Physicists are still trying to understand why the universe didn’t annihilate itself and why this asymmetry exists.

In fact, apart from dark matter and dark energy, the most captivating mysteries in modern day physics center on antimatter. So let’s delve into the history of this exotic stuff.

The Origins of Antimatter

Antimatter was first referenced in 1898 by Arthur Schuster, a British physicist. Schuster wrote two letters to Nature where he hypothesized antiatoms, their presence in the Solar System, and how they would react when they came into contact with regular atoms.

“Large tracts of space might thus be filled, unknown to us, with a substance in which gravity is practically non-existent, until by some accidental cause, such as a meteorite flying through it, unstable equilibrium is established, the matter collecting on one side, the anti-matter on the other until two worlds are formed separating from each other, never to unite again.”

Schuster goes on to discuss how matter and antimatter can coexist in bodies of small mass. He suggested that they repel one another, almost like the opposite poles of magnets. This was just the beginning. Paul Dirac was the one who took Schuster’s hypothesis and worked it into what we recognize today.

Dirac developed a theory, which is now known as the Dirac equation, that combined quantum mechanics (used to describe the subatomic world) with Einstein’s special relativity (which explains the world of the very large). It explained how electrons, traveling at near light-speed, behave.

Notably, his equation—which he referred to as “beautiful” (clearly modesty is not to be counted among Dirac’s faults)—worked with both electrons with negative charge and a particle that behaves like an electron but has a positive charge.

He realized, eventually, that his equation prediced antiparticles. Dirac hypothesized that for every particle that one can imagine, there exists an antiparticle that is nearly identical, but has an opposite electric charge. If you were to add together antiprotons, antineutrons, and anti-electrons, you get anti-atoms and antimatter.

The insight alerted scientists to the possibility that there could be entire galaxies and universes made of antimatter.

Ultimately, Dirac’s research marked the first time that something which was never before seen in nature was “predicted.” And his work earned him the title, “the Father of Antimatter.” For his work, he was awarded the Nobel prize in physics at the age of 31.