“Anxiety Cells”

In a new study, neuroscientists at Columbia University Irving Medical Center (CUIMC) and the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) identified brain cells that appear to control anxiety. While the researchers found these “anxiety cells” in the brains of mice (specifically in the hippocampus) Rene Hen, Ph.D., one of the study’s senior investigators, believes that the cells likely exist in the human brain as well.

When these “anxiety cells” fire, they send a message to the regions of the brain which trigger anxious behavior. For the mice in the study, these anxious behaviors included avoiding an area that made them feel unsafe or leaving that area for somewhere safe. In the study’s press release, Hen explained that the cells only fire when the animals are in places that are scary for them. “For a mouse, that’s an open area where they’re more exposed to predators, or an elevated platform.”

Previous research has implicated a number of different cells in anxiety, but these cells are the first scientists have found that are related to the actual state of anxiety in an animal – regardless of their environment.

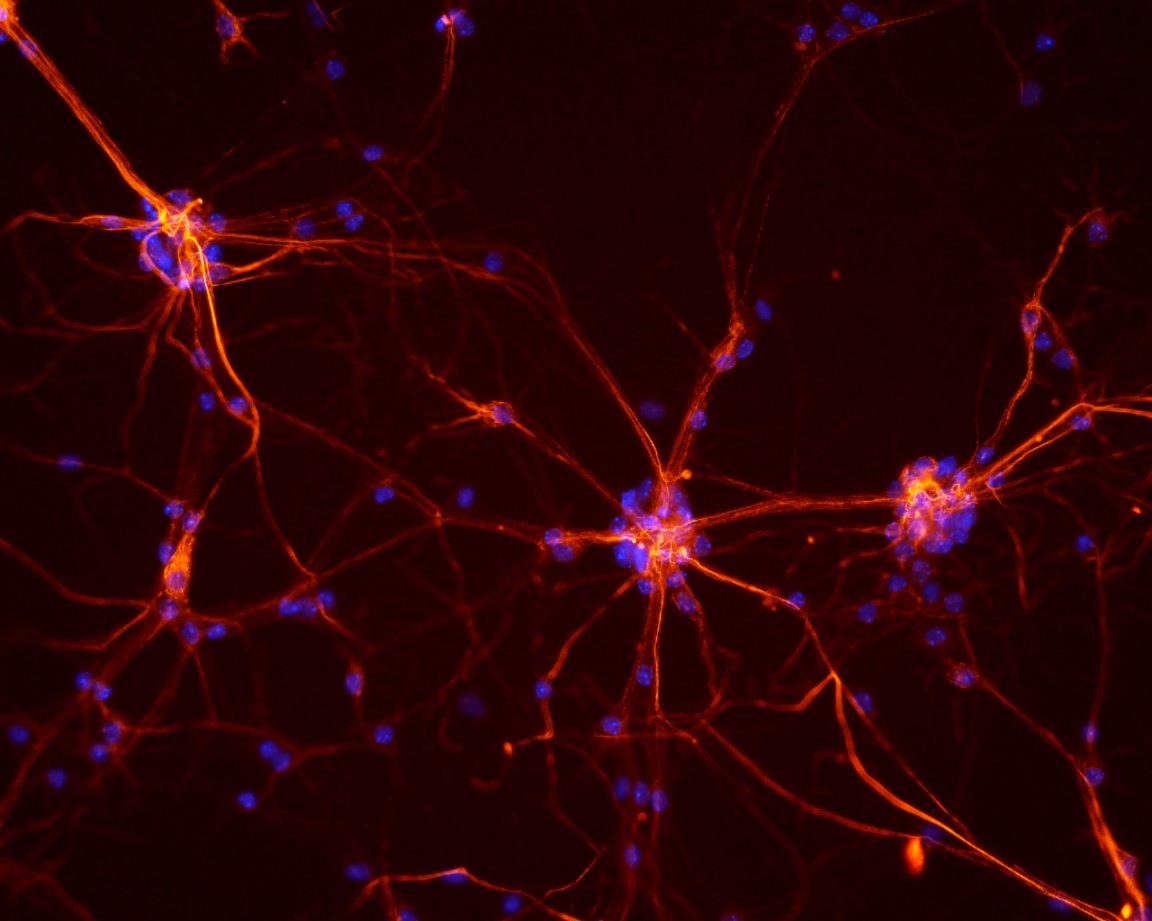

In the study, published in the journal Neuron, researchers used a technique known as optogenetics to control the signaling of the neurons. When they “turned up” the cells’ activity in the brain, the mice exhibited higher levels of anxious behavior and did not want to explore their surroundings.

Treating Anxiety

Anxiety has a very specific purpose: it helps an animal sense danger so they can avoid potentially dangerous environments. Anxiety is a natural, useful part of life — until it becomes uncontrolled. At that point, it becomes not just unhelpful, but distressing. Even harmful in and of itself.

Treating anxiety conditions in humans can be tricky, as many of the current methods for treating anxiety have significant drawbacks. Among the most commonly prescribed medications, several come with a host of side effects. Even for patients who use a combination of therapy and medications, it can be difficult to find a treatment that’s effective.

“Now that we’ve found these cells in the hippocampus, it opens up new areas for exploring treatment ideas that we didn’t know existed before,” said Jessica Jimenez, PhD, an MD/PhD student at Columbia University’s Vagelos College of Physicians & Surgeons and lead author of the study.

The findings from this research certainly could one day help develop new treatments for anxiety or improve the treatments we already have. Joshua Gordon, director of the National Institute of Mental Health (which helped fund research) told to NPR that “If we can learn enough, we can develop the tools to turn on and off the key players that regulate anxiety in people.”

While the research is promising, Gordon did caution that it’s not going to lead to a cure-all. “You can think of this paper as one brick in a big wall,” he said.