Last summer, a research group from the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) quietly published the results of a new approach in the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. What they found was striking. Although the size of the study was small, every participant demonstrated such marked improvement that almost all were found to be in the normal range on testing for memory and cognition by the study’s end. Functionally, this amounts to a cure.

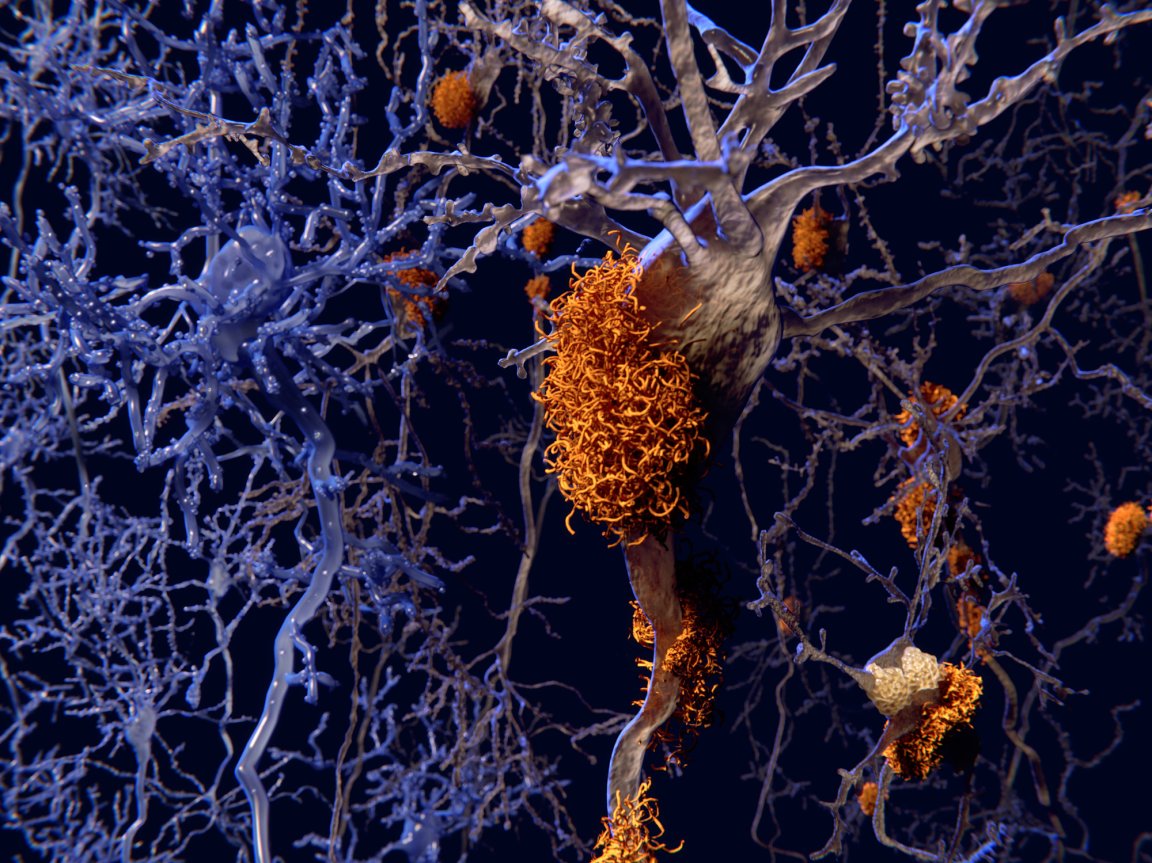

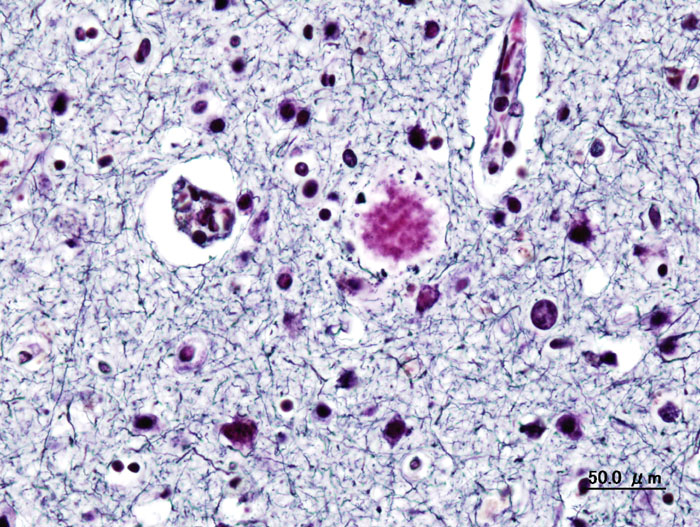

These are important findings, not only because Alzheimer’s disease is projected to become ever more common as the population ages, but because current treatment options offer minimal improvement at best. Last July, a large clinical trial found little benefit in patients receiving a major new drug called LMTX. And after that, another hopeful drug designed to target amyloid protein, one of the hallmarks of Alzheimer’s disease, failed its first large clinical trial as well. Just two months ago, Merck announced the results of its trial of a drug called verubecestat, which is designed to inhibit formation of amyloid protein. It was found to be no better than placebo.

The results from UCLA aren’t due to an incredible new drug or medical breakthrough, though. Rather, the researchers used a protocol consisting of a variety of different lifestyle modifications to optimise metabolic parameters – such as inflammation and insulin resistance – that are associated with Alzheimer’s disease. Participants were counselled to change their diet (a lot of veggies), exercise, develop techniques for stress management, and improve their sleep, among other interventions. The most common ‘side effect’ was weight loss.

The study is notable not only for its remarkable outcomes, but also for the alternative paradigm it represents in the treatment of a complex, chronic disease. We’ve spent billions of dollars in an effort to understand the molecular basis of Alzheimer’s in the hope that it will lead to a cure, or at least to more effective therapies. And although we have greatly enlarged our knowledge of the disease, it has not yielded many successful treatments.

The situation is analogous in kind, if not quite degree, to the many other chronic diseases with which we now struggle, such as diabetes and cardiovascular disease. While we do have efficacious medications for these conditions, none work perfectly, and all have negative effects. Our understanding of the cellular processes at the root of these diseases is sophisticated, but technical mastery – the grail of a cure – has remained elusive.

Acknowledging these difficulties, the researchers at UCLA opted for a different approach. Beginning from the premise that Alzheimer’s disease is a particular manifestation of a highly complex system in disarray, they sought to optimise the system by changing the inputs. Put another way, the scientists chose to set aside the molecular box which has proven so vexing, and to focus instead on the context of the box itself. Although we cannot say precisely how the intervention worked, on a cellular level, the important thing is that it did work.

The method isn’t entirely novel. Researchers have already shown that multi-faceted, comprehensive lifestyle interventions can significantly improve outcomes in cardiovascular disease, diabetes and hypertension. But it’s difficult for these approaches to gain traction for two reasons. First, these protocols are more challenging than simply taking a pill at bedtime. Patients need ongoing education, counselling and support to effect meaningful change. And second, the pharmaceutical mode of treatment is deeply embedded within our current medical system. Insurance companies are set up to pay for medication, not lifestyle change; and physicians are taught pharmacology, not nutrition.

Despite these difficulties, it’s time to start taking these approaches much more seriously. The prevalence of Alzheimer’s disease is expected to triple over the next three decades, to nearly 14 million in the United States alone. Diabetes and other chronic diseases are expected to follow a similar trajectory. Trying to confront this epidemic with medication alone will raise a new host of problems, from prohibitive cost to adverse effects, without addressing any underlying cause. We know that comprehensive lifestyle modification can work for many chronic diseases, in some cases as well as medication. It deserves more than passing mention at the end of an annual check-up – it’s time to make it a cornerstone in the treatment not only of Alzheimer’s disease, but of all chronic disease.![]()

Clayton Dalton

This article was originally published at Aeon and has been republished under Creative Commons.