After launching late last year, NASA’s revolutionary James Webb Space Telescope is finally getting ready to fixate its numerous golden mirrors on distant targets.

Intriguingly, though, one of its 13 early targets isn’t so distant at all — at least in the grand scheme of things. It’ll be looking at Jupiter, the iconic gas giant in our own star system. Of course, we already know quite a bit about the planet already— so why investigate it using the JWST if it can have a closer look at far more distant objects?

“We’ve been there with several spacecraft and have observed the planet with Hubble and many ground-based telescopes at wavelengths across the electromagnetic spectrum (from the UV to meters wavelengths),” Berkeley astronomer Imke de Pater, leader of the Jupiter observation team, told Digital Trends, “so we’ve learned a tremendous amount about Jupiter itself, its atmosphere, interior, and about its moons and rings.”

“But every time you learn more there are things you don’t yet understand — so you always need more data,” she added.

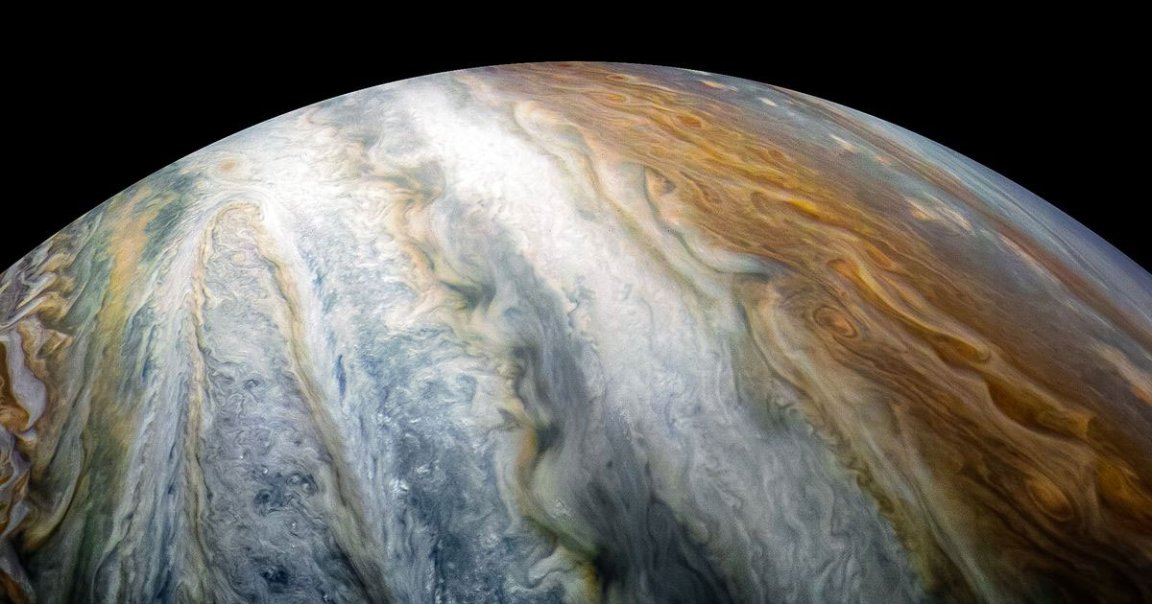

For instance, we still don’t know how an awful lot about the gas giant’s atmosphere, with massive storms roiling on its surface. The planet’s Great Red Spot, in particular, has fascinated astronomers since its discovery in 1830. It’s a storm so massive, in fact, that you could easily fit the Earth in the area it takes up.

“We’ll be looking for signatures of any chemical compounds that are unique to the [Great Red Spot]… which could be responsible for the red chromophores,” Leigh Fletcher, senior research fellow in planetary science at the University of Leicester in the UK, said in a 2018 NASA statement about the project, referring to particles responsible for the storm’s unusually red color.

“If we don’t see any unexpected chemistry or aerosol signatures… then the mystery of that red color may remain unresolved,” Fletcher added.

The JWST will also take a closer look at Jupiter’s moons Io and Ganymede, the latter being the only known moon that has its own magnetosphere.

The space telescope is the ideal candidate for the job.

“The biggest advantage is at the mid-infrared wavelengths,” de Pater told Digital Trends. “We can observe at some of these wavelengths from the ground, but the Earth’s atmosphere is so turbulent that what we get on the ground, we can’t calibrate the observations very well.”

Right now, the JWST is still busy aligning its mirrors — but soon, it’ll finally be prime time.

“In the first year of science operations, we expect Webb to write entirely new chapters in the history of our origins — the formation of stars and planets,” Klaus Pontoppidan, the Space Telescope Science Institute project scientist for Webb, said in a recent NASA blog post.

Before gazing at Jupiter, the observatory’s Mid-Infrared Instrument (MIRI) will have to be cooled to about 7 Kelvin, or about -447 Fahrenheit, to adjust to its frosty surroundings in deep space.

But once it’s ready, astronomers are already excited about what it will be able to see.

“The imager promises to reveal astronomical targets ranging from nearby nebulae to distant interacting galaxies with a clarity and sensitivity far beyond what we’ve seen before,” Alistair Glasse, Webb-MIRI Instrument Scientist at the Astronomy Technology Center in the UK, said in a recent post.

And considering it’s proximity, Jupiter should be child’s play for the JWST.

Updated to correct an error in the temperature the James Webb’s MIRI instrument will eventually be cooled to.

READ MORE: One of James Webb’s first targets is Jupiter. Here’s why [Digital Trends]

More on JWST: NASA Is Keeping the James Webb Telescope’s First Target Secret