A Tiny, Huge Discovery

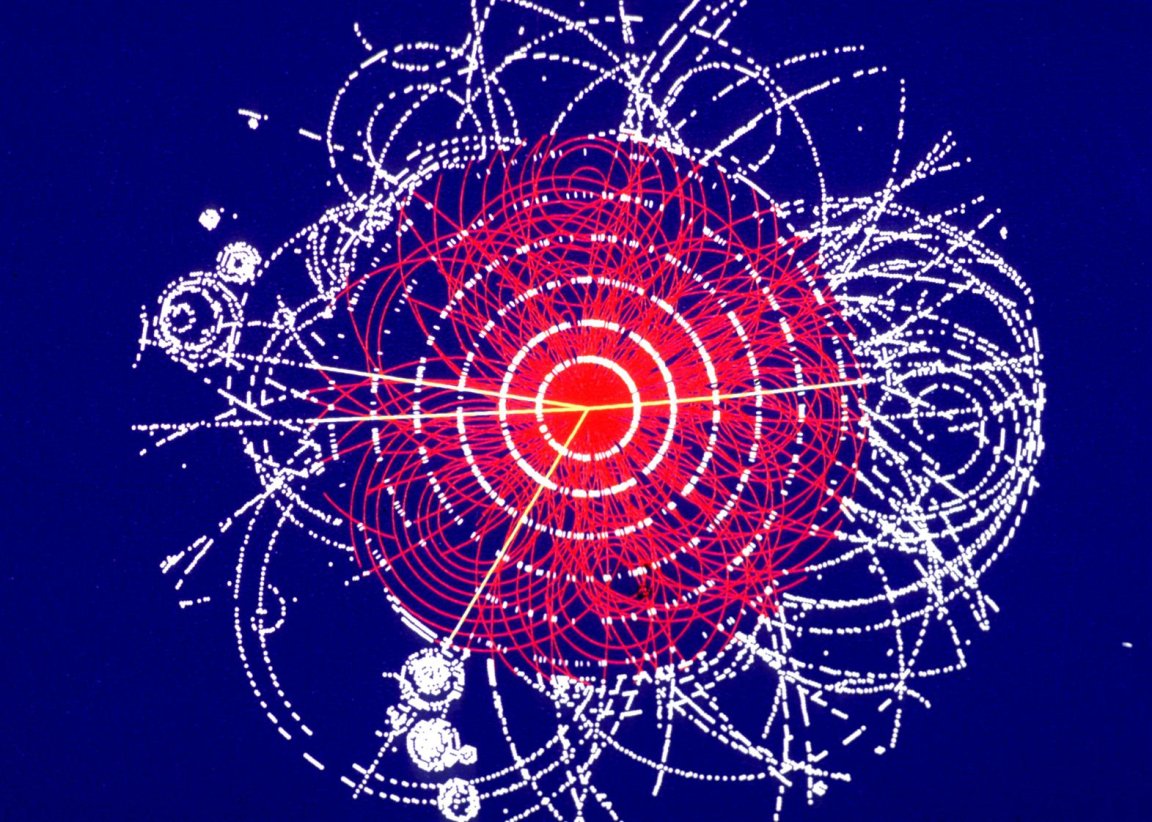

On July 4th, 2012, researchers from the European Organization for Nuclear Research (CERN) made a big announcement. They had observed the Higgs boson, an elementary particle predicted by one of the best models for physics in the universe. “‘We discovered the particle that makes it possible for atoms to form in the first place.’ That’s much sexier,” James Beacham, a particle physicist at CERN, said of the discovery in an interview at Brain Bar Budapest, a future-oriented festival in Hungary held in June.

Those in the know might have been anticipating this observation for decades, but that didn’t dampen the excitement. The discovery marked the culmination of a 40-year scientific effort, as Beacham noted, and it garnered the Nobel Prize in physics in 2013.

Most discoveries in physics remain far from the public eye, esoteric and uninviting to the masses. But this discovery of a new particle, predicted by many and finally observed after so much work and anticipation — was different. It sparked a media frenzy, the excitement from which continued well beyond the days and weeks after the discovery was announced.

Moving On

There was great success and celebration, but every party has to end. After the discovery of the Higgs boson, CERN scientists seemed to fall into a slow, sullen post-discovery period, if a recent article from the New York Times is to be believed.

Beacham paints a different picture. From his telling, CERN isn’t stalling out, it’s in a honeymoon phase. The Higgs boson discovery really just answered one question: whether or not it existed, he said at the June event. “The second we found [the Higgs boson], that was not enough for us. We want to know every single one of its properties,” Beacham said. “Even before we announced it…we were ahead.” This discovery had been predicted for so long that, while the observation itself was thrilling, CERN researchers were already working on what else this observation could reveal.

Discovering the Higgs boson created many more questions than it answered — physics is funny like that. “So for us, there was no celebration downtime,” Beacham said. That’s in part because the Higgs is “a crazy particle,” he added. “It’s unlike anything else that we know of in the Standard Model.” Predicting the Higgs boson came with so many precise conditions that its existence allows scientists to test a number of other conditions that the model predicts.

This is how Beacham and a lot of other CERN scientists are spending their time these days — exploring questions never before answered, with this discovery serving as a magnificent jumping off point. “Now, the current and foreseeable future for ATLAS [one of the five major experiments at CERN] is to make sure that we’re not going to miss anything,” he said. That is, he admits, a little vague, but that’s the beauty of this type of exploration. There are still particles that physicists have predicted, but which no one has yet observed. The more we discover, the more complex the universe becomes to us. “[CERN is] one of the most sophisticated devices that anyone has ever designed, and we have to do our damnedest to make sure that we don’t miss anything,” Beacham said.

There were those who viewed the discovery of the Higgs boson with a sort of finality — a tremendously anticipated observation that would tell researchers one way or another if they were right or if somehow they’d misinterpreted the trusted standard model. But that’s not how physicists see it.

Physics, like many fields that pursue knowledge and truth, is a winding path punctuated by jumps and halts. Beacham wasn’t able to predict exactly what the next big discovery might be, but the curiosity and uncertainty are part of what makes discovery and the endless quest to answer “what if?” so magical.