Cybersecurity on the Brain

In our increasingly connected world, cyber attacks have become more and more common. These attacks can range from relatively small incidents of personal data leaking online to bigger cases involving entire institutions.

In 2014, one major hack targeted Sony Pictures, and in 2015, the federal Office of Personnel Management found out that it had been breached by Chinese hackers — arguably that year’s biggest hack — for at least a year before it was discovered. Even security and surveillance firms like Kaspersky Lab and Hacking Team have been attacked, as has then-CIA director John Brennan’s personal AOL account. Last year’s list of infamous hacking cases includes the major Yahoo data breach, a series of attacks that targeted the Democratic National Committee, and the major DDoS botnet attack that crippled most of the U.S. internet in October.

It’s no surprise, therefore, that companies spend as much as $100 billion annually on keeping computers and networks secure. However, according to Anthony Vance, associate professor at Brigham Young University, we need to examine the human brain if we want to come up with more effective cybersecurity measures.

Better Warnings, Better Security

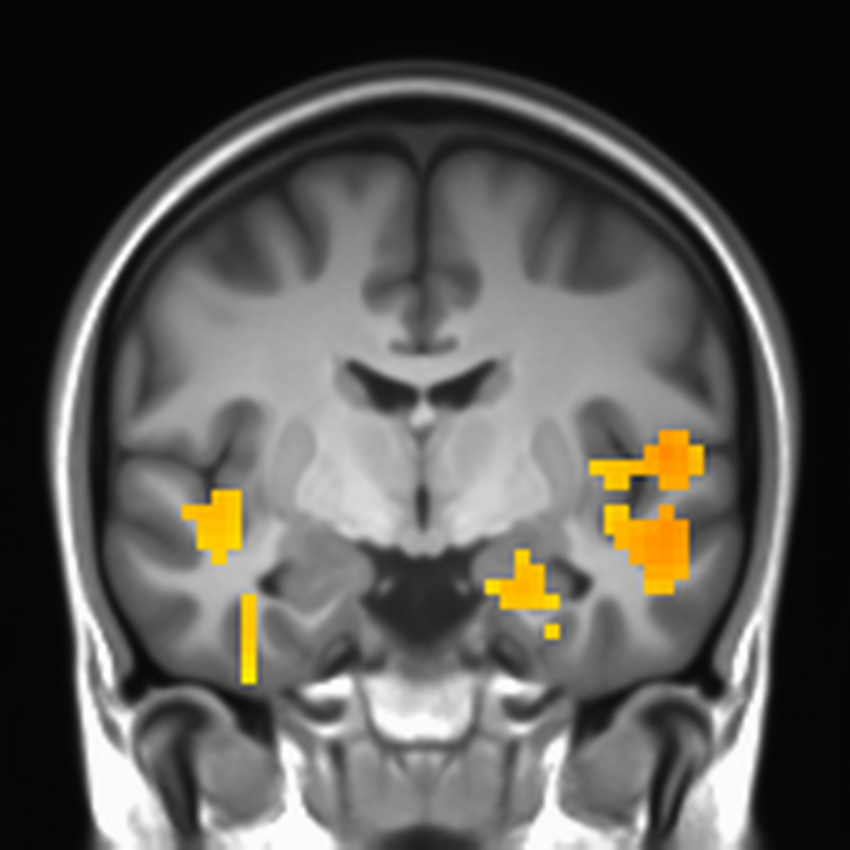

“Security professionals need to worry not only about attackers but the neurobiology of their users,” Vance said this week at the Enigma security conference in Oakland, California. His lab studied functional MRI scans of people’s brains to better understand the unconscious mechanisms that affect how they perceive often-ignored security warnings.

They noted that people tended to react hastily to a warning message or a strange email and concluded that multitasking is partly to blame for this reaction. When people encountered security warnings while in the middle of performing another task, areas in the brain connected to fully engaging with the warnings showed diminished activity. Vance’s studies also showed that people tend to be more dismissive of security warnings the second time they see them. This habituation effect could be reduced by breaking the usual rules of software design and developing security alerts that slightly change in appearance each time they pop up.

The research led to Vance working with Google to craft and test security warnings that people would be less likely to dismiss in the Chrome web browser. Google’s engineers plan to implement these features into an upcoming version of Chrome, they told Vance. The improved approach includes simple adjustments like waiting until someone finishes watching a video or uploading a file before showing the security warning.

Essentially, the tech world needs to find ways to get users’ brains to pay attention to security warnings. “This shows the potential to use neuroscience to understand people’s behavior and validate new user interface designs,” Vance explained. “Our security UI should be designed to be compatible with the way our brains work.” Finding ways to decrease the number of online hacks just may depend on it.