Books Are Bound in Human Flesh

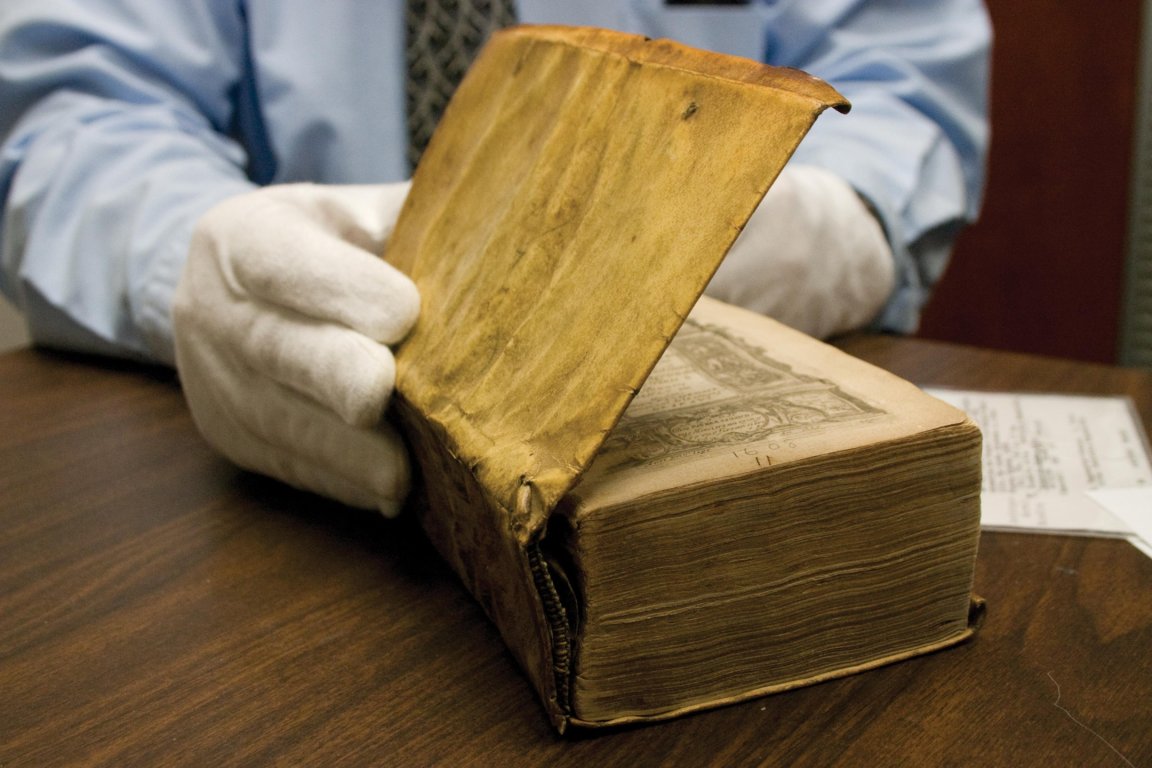

Ever had a book you loved so much, you could just die? Careful now. It seems that such things have happened in the past. As it turns out, there are a few historical individuals who give new meaning to the idea of “spending forever in the library.” Mostly, this is because their skin binds two of the books in Harvard’s 15-million-volume collection.

That’s right. Harvard has human flesh book covers. Of course, with over 15 million books in the collection, it is impossible to know how many of the books are actually bound in human flesh. Though this determination could be made with extensive testing, it would be a needlessly lengthy and time-consuming process. So, for now, we will just have to be content with the two.

This shudder-inducing mental image may seem barbaric to people living in modern times (and make no mistake, it is), but such practices were thought of differently in the early 17th and 18th centuries. During this time, individuals kept parts of loved ones (literally) as a kind of memento. It’s a bit like holding onto a lock of someone’s hair. Ultimately, this practice became popular during the 17th century and continued throughout the 1800s.

The 1880s text called “Des destinées de l’ame” is actually a collection of essays on the nature of the human spirit, written by French poet Arsène Houssaye. Notes that came with the acquisition of the book revealed that the binding comes from “the back of the unclaimed body of a woman patient in a French mental hospital who died suddenly of apoplexy.” Yes, it is the skin of a mental patient (not that it makes the whole thing any better or worse).

A friend of the author—who also appears to be responsible for the text’s binding—justified this unique composition it in a letter, writing that, “a book on the human soul merited that it was given a human skin.” An eminently reasonable justification.

How Einstein’s Disembodied Brain Toured the Country

When Albert Einstein died on April 18th, 1955 in Princeton, New Jersey, rigor mortis had barely set in when he—or at least pieces of him—embarked on a highly-publicized journey that didn’t come to a resolution until decades later.

Hours after Einstein died from an abdominal aortic aneurysm, a pathologist named Thomas Harvey removed Einstein’s brain and chopped it up into more than 240 pieces; many were preserved in jars of formaldehyde that he kept at his home, while others were left stewing in the trunk of his car (as if this story wasn’t creepy enough).

The worst part of this whole scenario is that Harvey did this despite Einstein’s wishes to be cremated. Harvey was censured by his employer, and it looked like he would lose his job; however, he was able to keep his employment by receiving permission from Einstein’s son after the fact. But the creepiness didn’t end there.

Harvey eventually lost his job anyway, as he refused to hand the brain over to research scientists (he was only allowed to keep it in the first place because he told Einstein’s family that the makeup of Einstein’s brain was the secret to his brilliance with mathematics and physics, and the researchers wished to study it). Once he was fired, Harvey took Einstein’s brain with him (yeah, he stole it).

Though he did give some portions away to researchers, for years, he kept pieces for himself as he moved around the country. The remaining parts were with him, and are said to have been kept in jars inside a box marked ‘Costa Cider.’

In 1997, magazine writer Michael Paterniti drove with Harvey from his home in New Jersey to California to meet Einstein’s granddaughter; all the while, the brain was kept safe in Tupperware in the trunk (this is some seriously professional science we’re talking about). However, she explained to Harvey that she did not want the brain (who wouldn’t want to be a fly on the wall for that conversation?). So Thomas Harvey and Michael Paterniti left her and headed home, where Harvey continued to hang on to the brain. Eventually, he decided to take the brain back to its rightful home at Princeton Hospital.

The Tuskegee Syphilis Study

Between 1932 and 1972 in Tuskegee, Alabama, 399 poor and mostly illiterate African-American men were denied treatment for syphilis. By the end of the study, only 74 of the test subjects were still alive. Over the course of this study, twenty-eight of the men had died directly of syphilis, 100 died of related complications, 40 of their wives were infected, and 19 of their children were born with congenital syphilis.

In a horrific violation of human rights (note that this didn’t happen during medieval times, but in the mid to late 20th century) the individuals enrolled in the study did not give informed consent and were not told of their diagnosis. Instead, they were lied to. They were told they simply had “bad blood,” and were conned into participating by being told that, in return for their participation, they could receive free medical treatment and burial insurance in case of death.

Admittedly, when the study started, treatment was highly toxic and dangerous. This trial began because scientists hoped to determine whether or not it was better to just leave people untreated (though this does not justify lying to patients and failing to seek informed consent). Moreover, in the 1940s, the widespread availability of penicillin essentially made the study moot. Penicillin treatment does not lead to widespread death. In fact, it is a highly reliable form of treatment. As the Center for Disease Control notes, “The advisory panel found nothing to show that subjects were ever given the choice of quitting the study, even when this new, highly effective treatment became widely used.”

Another problem with this experiment is that, as previously mentioned, individuals were not told that they had this condition. As a result, they were not able to make sound decisions in order to protect their partner(s) during intercourse. In 1974, a $10 million out-of-court settlement was reached. As part of the settlement, the U.S. government promised to give lifetime medical benefits and burial services to all living participants. Of course, money cannot give them back their lives or their health.

Want more creepy science tales? See part II, “More Strange, Morbid, and Scary Stories in Science,” here.