Researchers at Boston University may have discovered a new and effective way of stimulating and improving memory in older individuals. The best part? It’s noninvasive — all you need to do is wear a headset that sends electric currents to targeted parts of the brain.

If that sounds too good to be true, we get it. Scientists have been chasing treatments for memory loss for a long time, and it’s important to note that the results of the researchers’ study, published in the journal Neuroscience, are preliminary. The results, however, sound genuinely promising, and could very well lay the foundation for treatments for conditions including Alzheimer’s and dementia.

The headset works by sending electric currents to the prefrontal and parietal cortexes, which are both understood to contribute to storing and recalling information. Since brains function by way of both chemical and electric messaging, the scientists found that electric currents were able to enhance memory-specific brainwaves.

“It’s sort of connecting to the so-called language of the brain,” Dr. Robert Reinhart, study coauthor and director of the Cognitive and Clinical Neuroscience Laboratory at Boston University, told the BBC, “that speaks to itself and communicates with itself through electrical impulses.”

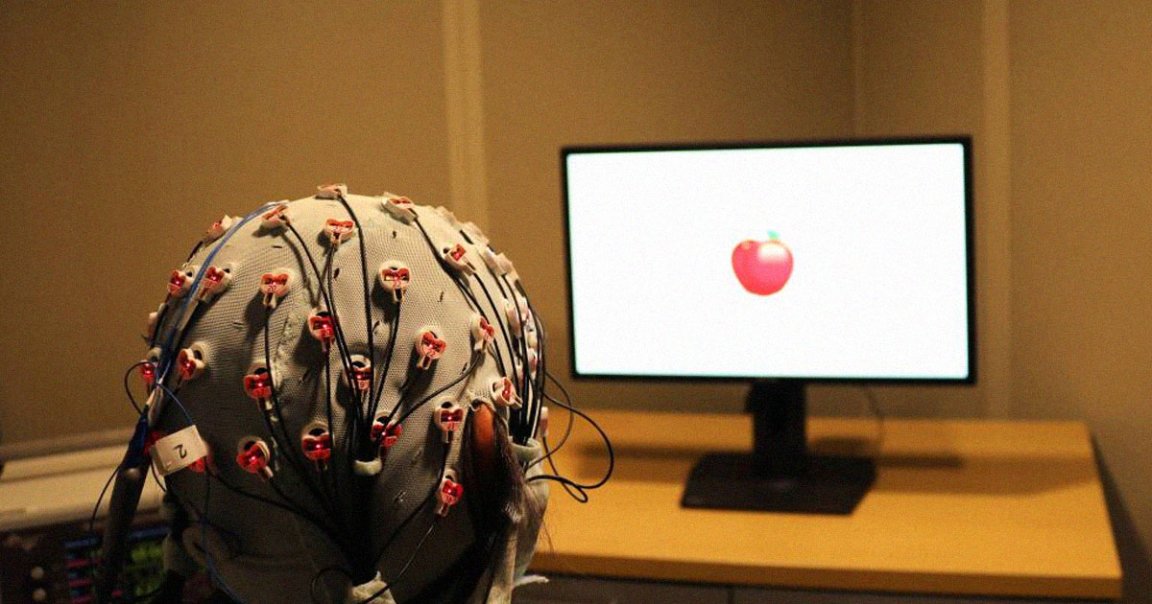

For the first round of testing, the researchers enlisted the help of 60 volunteers aged between 65 and 88, split into three groups of 20 participants. They each wore the electrode-laden cap for 20 minutes daily over the course of four days — one group received high-frequency (60 hertz) gamma waves to their prefrontal cortex, a second group received low-frequency (4 hertz) theta waves to the parietal cortex, and a control group received a placebo.

For context, gamma waves are quick and short, linked closely to memory, cognition, and focus. Theta waves, on the other hand, are long and slow; a brain on theta waves is likely in a still, meditative state.

During the daily treatments — while participants’ brains were being zapped with the waves — the scientists asked them to memorize certain words. At the end of the treatment, each individual then immediately performed word recall tests.

The results were modest, though hopeful. Seventeen of the 20 individuals who received the gamma waves showed improvement in long-term memory, defined by the scientists as the ability to remember the earliest words of each recall exam. Eighteen of 20 of the theta wave bunch showed improvement in short-term memory, defined by the scientists as the ability to remember the last words in the same test.

As Reinhart explained to CNN, this “translates to the older individuals recalling, on average, four to six words more out of the list of 20 words [in comparison to the control group] by the end of the 4-day intervention.”

The scientists ultimately tested 150 people in total, with subsequent rounds of testing that followed confirming these results. And perhaps most excitingly, the study claims that participants still showed memory improvement about a month after testing.

Importantly, though, it should be noted that while these results do say something about short-term memory, other doctors in the field aren’t convinced that it actually says that much about long-term recall.

“Cognitive experts would say what you recall from an hour ago is long-term memory,” Rudy Tanzi, a professor of neurology at Harvard Medical School who was not involved in the research, told CNN. “But with regard to Alzheimer’s clinical symptoms and age-related memory impairment, we would group this into short-term memory. When we say Alzheimer’s patients retain long-term memory, we are referring to recalling details of their wedding day.”

Tanzi has a point. Again, this research is very preliminary, and it won’t be curing Alzheimer’s anytime soon. Still, these scientists have opened the door to what, in essence, is the practice of spot-treating our powers of memory — and they’ve certainly laid the groundwork for new, exciting research to come.

READ MORE: Brain stimulation improves short-term memory in older adults for a month, study finds [CNN]

More on brain health: Scientists Fed Rats Sugary Soda for Two Months and They Got Demonstrably Stupider