Viable Editing

One of the most fascinating and promising developments in genetics is the CRISPR genome editing technique. Basically, CRISPR is a mechanism by which geneticists can treat disease by either disrupting genetic code by splicing in a mutation or repairing genes by splicing out mutations and replacing them with healthy code.

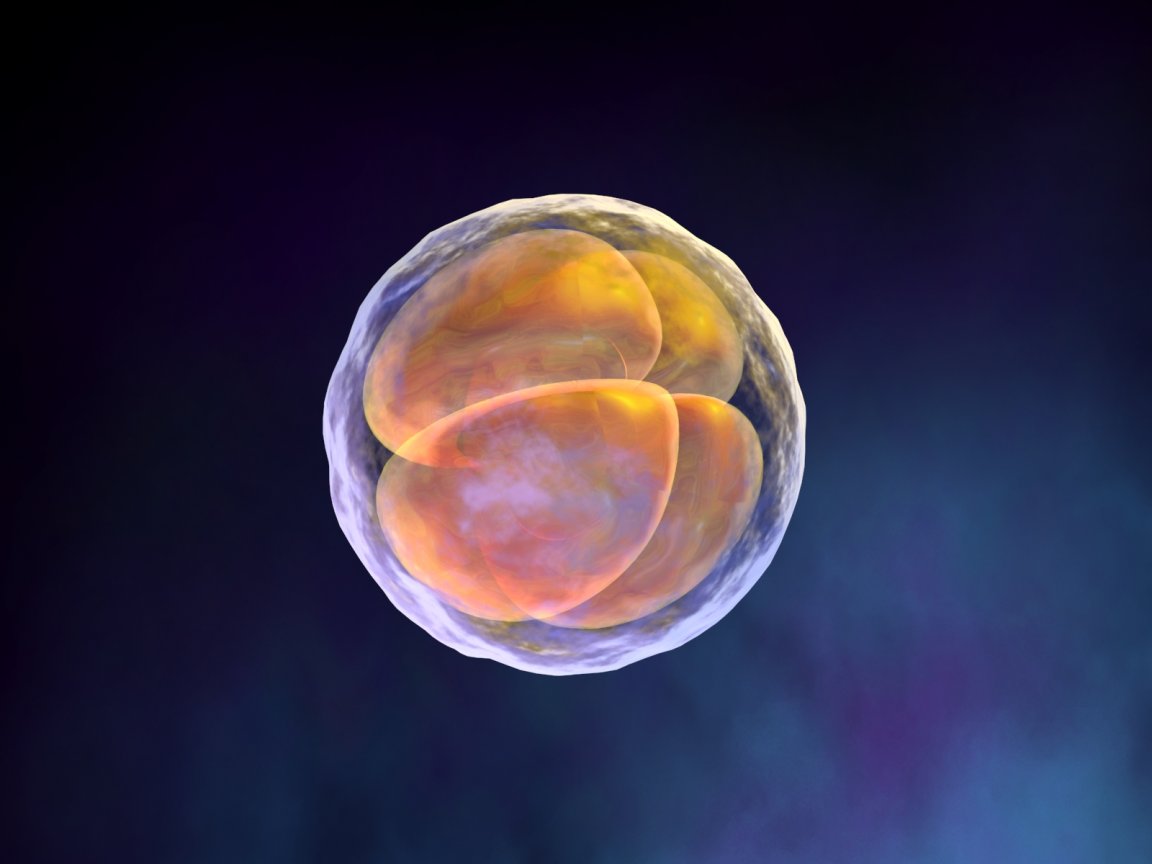

Researchers in China at the Third Affiliated Hospital of Guangzhou Medical University have successfully edited genetic mutations in viable human embryos for the first time. Typically, to avoid ethical concerns, researchers opt to use non-viable embryos that could not possibly develop into a child.

Previous research using these non-viable embryos has not produced promising results. The very first attempt to repair genes in any human embryos used these abnormal embryos. The study ended with abysmal results, with fewer than ten percent of cells being repaired. Another study published last year also had a low rate of success, showing that the technique still has a long way to go before becoming a reliable medical tool.

However, after experiencing similar results with using the abnormal embryos again, the scientists decided to see if they would fare better with viable embryos. The team collected immature eggs from donors undergoing IVF treatment. Under normal circumstances, these cells would be discarded, as they are less likely to successfully develop. The eggs were matured and fertilized with sperm from men carrying hereditary diseases.

Disease Sniper

While the results of this round of study were not perfect, they were much more promising than the previous studies done with the non-viable embryos. The team used six embryos, three of which had the mutation that causes favism (a disease leading to red blood cell breakdown in response to certain stimuli), and the other three had the mutation that results in a blood disease called beta-thalassemia.

The researchers were able to correct two of the favism embryos. In the other, the mutation was turned off, as not all of the cells were corrected. This means that the mutation was effectively shut down, but not eliminated. It created what is called a mosaic. In the other set, the mutation was fully corrected in one of the embryos and only some cells were corrected in the other two.

These results are not perfect, but experts still do find potential in them. “It does look more promising than previous papers,” says Fredrik Lanner of the Karolinska Institute. However, they do understand that results from a test of only six embryos are far from definitive.

Gene editing with CRISPR truly has the possibility to revolutionize medicine. Just looking at the development in terms of disease treatment, and not the other more ethically murky possible applications, it is an extremely exciting achievement.

Not only could CRISPR help eradicate hereditary disease, but it is also a tool that could help fight against diseases like malaria. There is a long road ahead for both the scientific and ethical aspects of the tech. Still, the possible benefits are too great to give up now.