A Whole Lot of Weird

To quote the late Douglas Adams (the beloved author of “The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy”), “Space is big. Really big. You just won’t believe how vastly, hugely, mind-bogglingly big it is. I mean, you may think it’s a long way down the road to the chemist’s, but that’s just peanuts to space.”

Truer words have never been spoken. In fact, the universe is so big that its size and scope is nearly incomprehensible, even to the most knowledgeable and open-minded individuals. With a diameter of more than 93 billion light-years, it’s not too surprising that so many extreme objects are lurking out there within it.

In this list, we’ve gathered the most massive and bizarre structures found in the universe.

Many of them are actually a collection of objects held together by the immense force of gravity. And since space is so big, none of our Earthly means of measuring distances will suffice, so for the sake of this article, we’re going to use light-years (the rate at which light travels through space in one year) as a unit of measurement.

Just so you have an idea of the kind of scales that we are talking about, light travels at 300,000 kilometers (186,000 miles) per second, which equals out to 5,878,000,000,000 miles (9,461,000,000,000 km) each year. Therefore, at this rate, it would take light more than 4 years of traveling at top speed to reach the Alpha Centauri triple-star system, and they are the closest stars to our Sun. Our galaxy, the Milky Way, is so long, it would take light more than 100,000 years of traveling to cross it.

10: Swift J1357.2

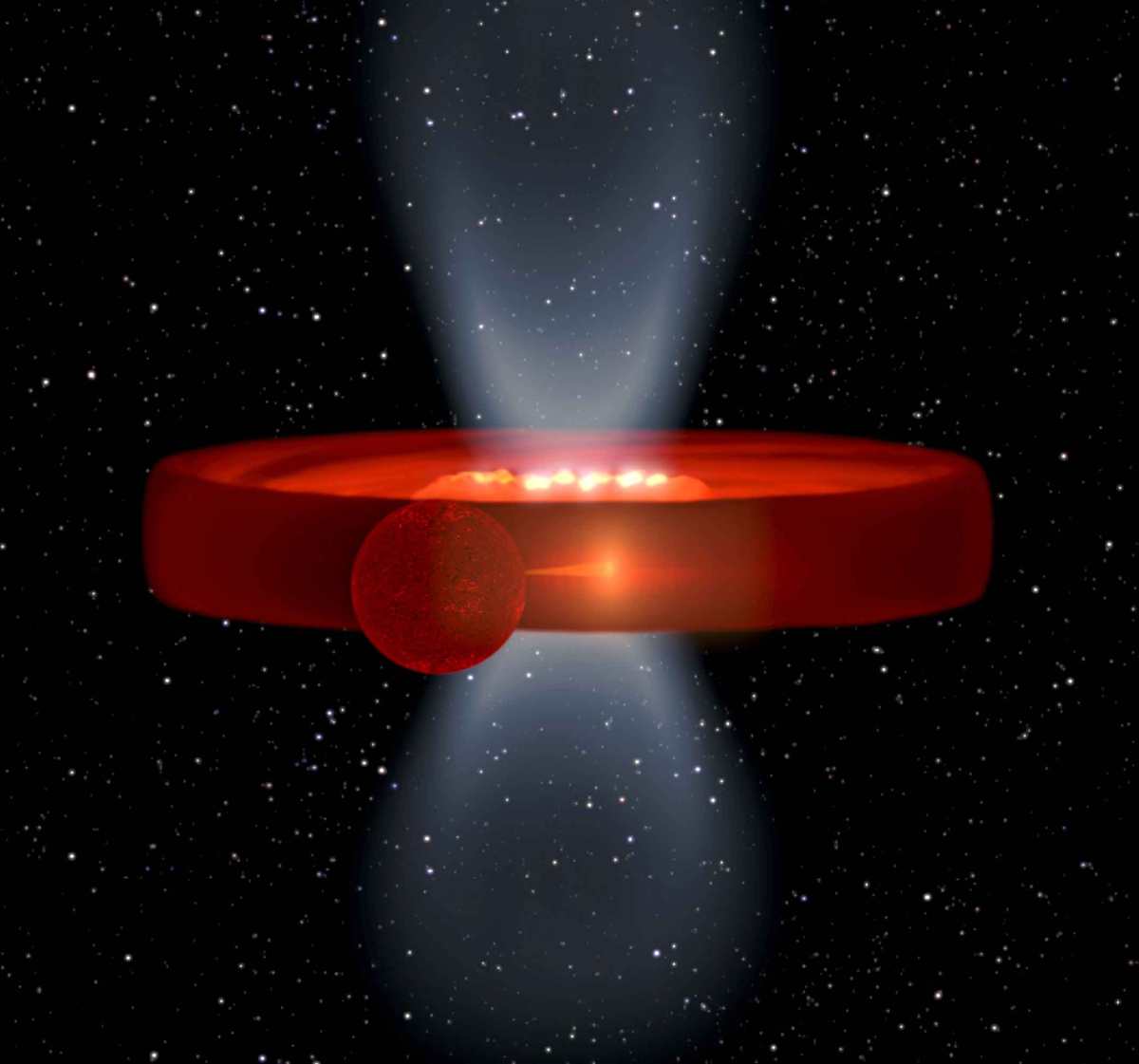

We start this list with the closest structure to Earth (and the only one actually located in our galaxy), formally known as Swift J1357.2. Located almost 5,000 light-years from Earth in the constellation of Virgo, the structure itself is one of the least understood of this list, but physicists believe that it is based around a binary system containing a star and a stellar-mass black hole.

The companion star in the system makes a complete orbit around the center of the system’s mass in the shortest orbital period known of at this time, just in 2.8 hours.

Contrary to popular belief, black holes are not cosmic vacuum cleaners that siphon all material located within the general vicinity of them. Instead, black holes only consume matter that dwells too close to them (coming within the so-called “event horizon,” which is basically the point beyond which nothing, not even light, can escape).

Gravitational perturbations can be the catalyst for this, causing an object (or a collection of matter) in a stable orbit around a black hole to veer off course, sending it spiraling inward. Because of this, it’s not uncommon for more material to collect than the black hole can consume at any given time. This material is known to build up and form something called an accretion disk.

The structure known as Swift J1357.2 is likely similar in design to one of these disks. Unlike its normal counterparts, this particular one has formed in the outer layer of the accretion disk and acts like a wave (traveling in an outward vertical direction instead of horizontally), which has resulted in a systematic “dimming” of the companion star every few seconds.

9. Hanny’s Voorwerp

Pictured at the left of the image below is IC 297, a spiral galaxy located about 650 million light-years from Earth in the constellation Leo Minor. To the right of the galaxy (separated by thousands of light-years in reality) is Hanny’s Voorwerp.

It’s one of the strangest structures in existence, and that says a lot, given the mind-boggling strangeness of some of the things Hubble (and several other groundbreaking telescopes) has unveiled. Besides being strange, the structure is also very massive, coming in at a diameter that exceeds that of the Milky Way (more than 100,000 light-years).

The most likely origin of the structure is a no-longer active quasar once located in IC 297’s central core. Sometime in the distant past, the quasar spat out all of the ghastly green material that twisted into filaments comprising this unique structure.

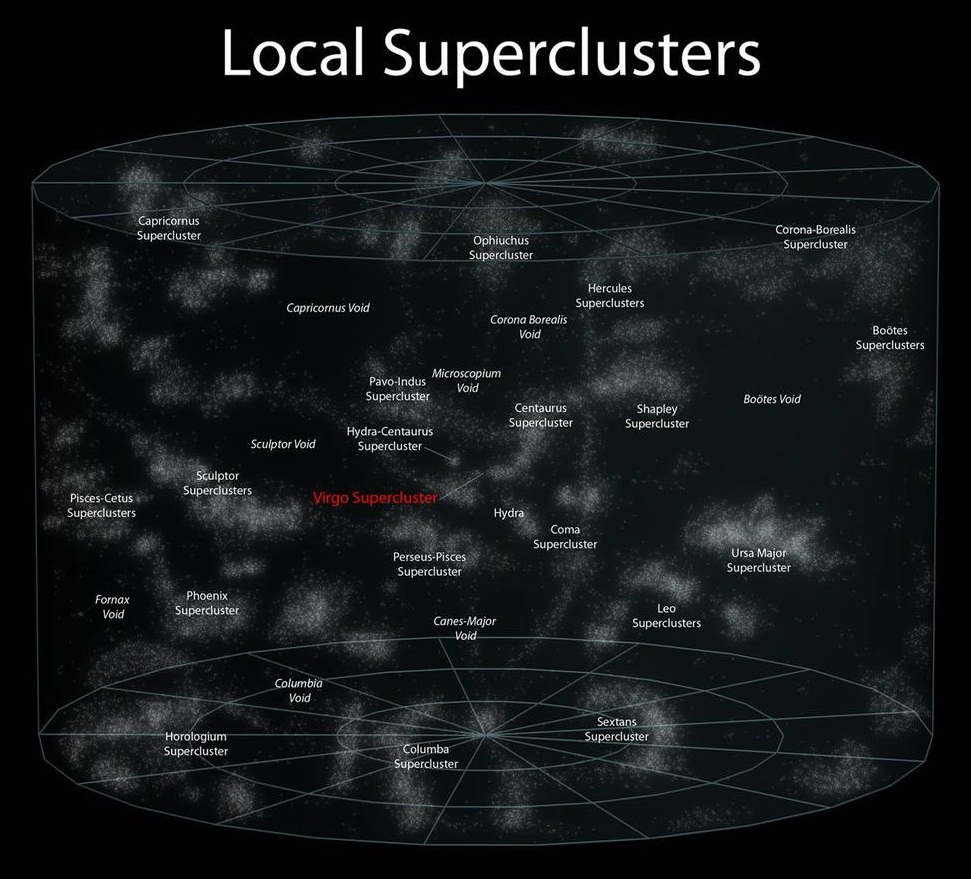

8. The Horologium-Reticulum Supercluster

This behemoth structure, containing more than 350,000 separate galaxies (30,000 large galaxies and 5,000 galaxy groups with more than 300,000 dwarf galaxies), is located about 700 million light-years from Earth — at least, the closest part of it is. This thing is so large, we aren’t entirely sure where the farthest end is, but it’s believed to be at least 1.2 billion light-years away from us, stretching across more than 550 million light-years in total.

Included in the Horologium-Reticulum Supercluster (with dozens of other superclusters pictured in the below image) is Abell 3266, one of the most massive regions in our local universe. Incidentally, a huge cloud of gas, stretching more than 5 million light-years across, is quickly approaching the cluster, which will reignite an era of star formation for the galaxies that will be impacted.

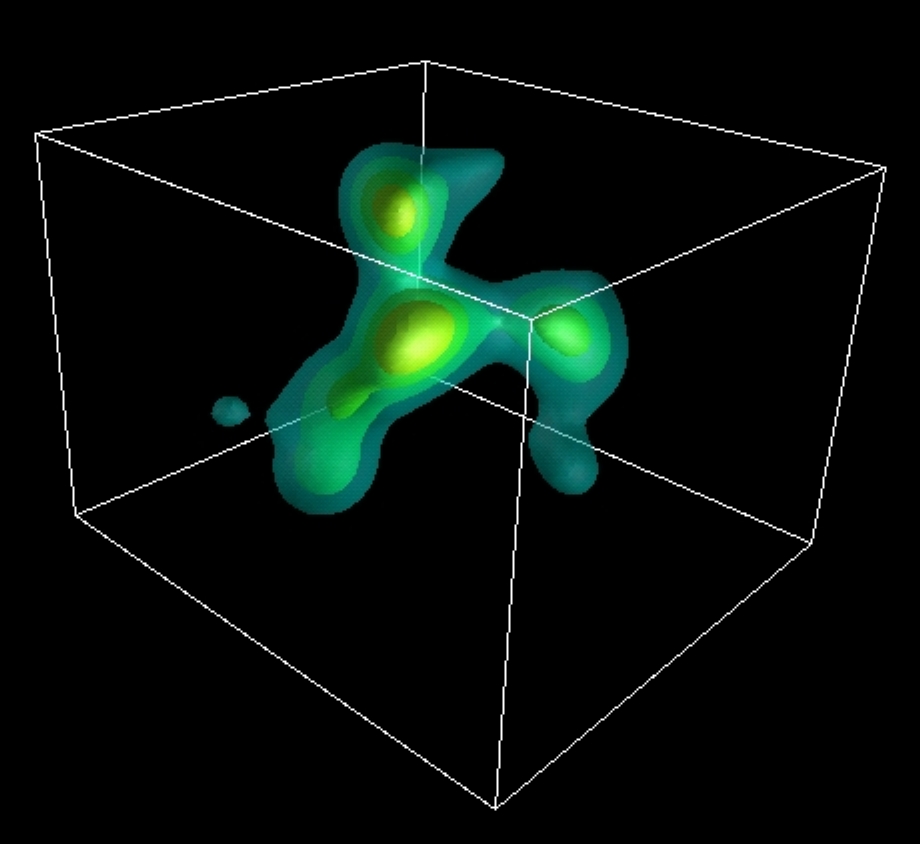

7. The Newfound Blog

Not only is the Newfound Blob one of the largest structures in the universe, it’s also one of the oldest and most distant. For a time, it actually was considered the largest. Then, modern astronomy came along, and we began to build more powerful telescopes that were capable of taking us back to the dawn of time.

The Newfound Blob comprises large bubbles of gas, with several galaxies called “Lyman Alpha Blobs” thrown in for good measure (gotta love the creativity!). This particular one, the largest known blob, is located about 11 billion light-years from Earth, stretching more than 200 million light-years across. Some of the individual bubbles are 400,000 light-years across, which is four times longer than our galaxy.

Its vast distance essentially means that the blob came into existence only 2 billion years after the Big Bang occurred. Factoring in the accelerating expansion of the universe, it’s safe to say that the blob is now much, much farther away from the location it was in when the light first left the region, beginning its journey through space to reach our planet.

Image Credit: National Astronomical Observatory of Japan

6. The Great Attractor

What is a list about space without a little bit of mystique? This entry will most certainly hit the proverbial spot, as it’s the Grand Poobah of unsolved cosmological mysteries.

When astronomers were observing one of the closest super-clusters to us, the Norma Cluster (located about 220 million light-years away), they noticed something strange and frankly perplexing. Something, which has since been dubbed “the great attractor,” is gravitationally tugging on galaxies located in the region, pulling the galaxies toward it at speeds exceeding 321,868 kilometers per hour (200,000 miles per hour).

The mass needed for the structure or object (the latter is unlikely) to exert the measured force on the galaxies is immense, leading some astronomers to believe that dark energy, the force driving the expansion of the universe, is to blame. If not, we may be missing key components needed to determine how gravity behaves on a macro-scale. Alternatively, I am rather fond of the notion that this is where all of the universe’s missing socks go.

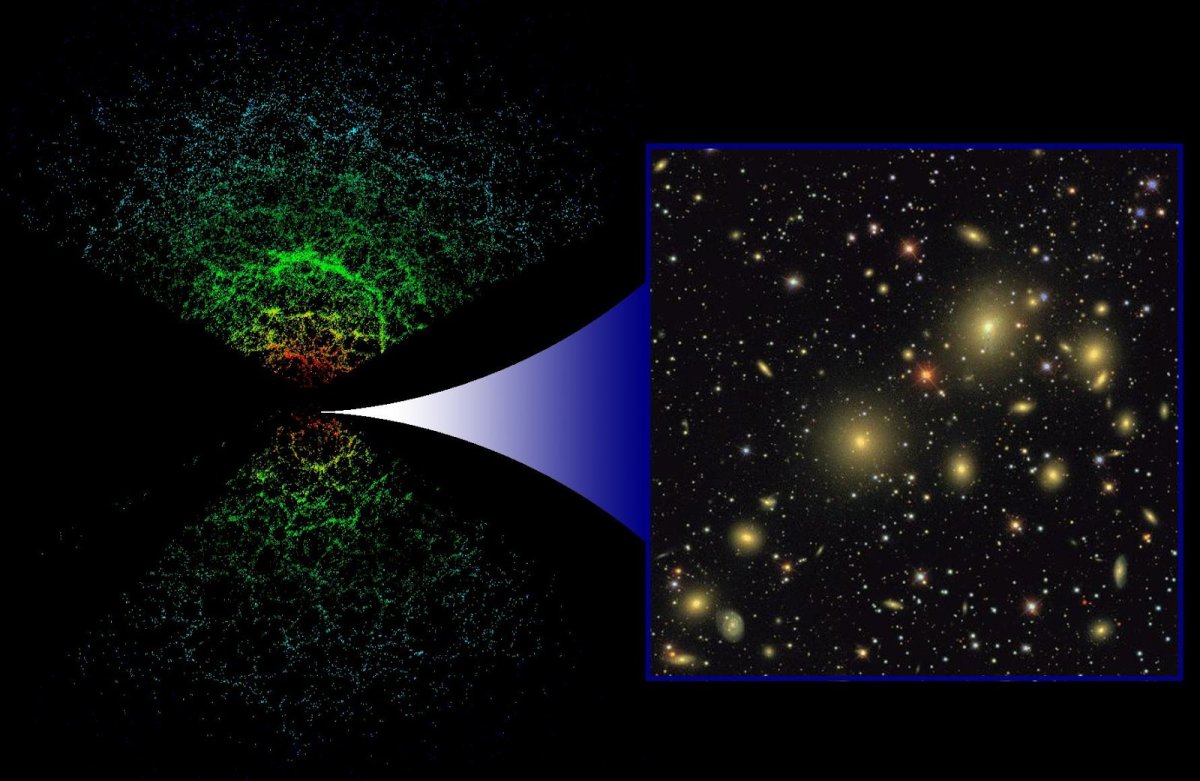

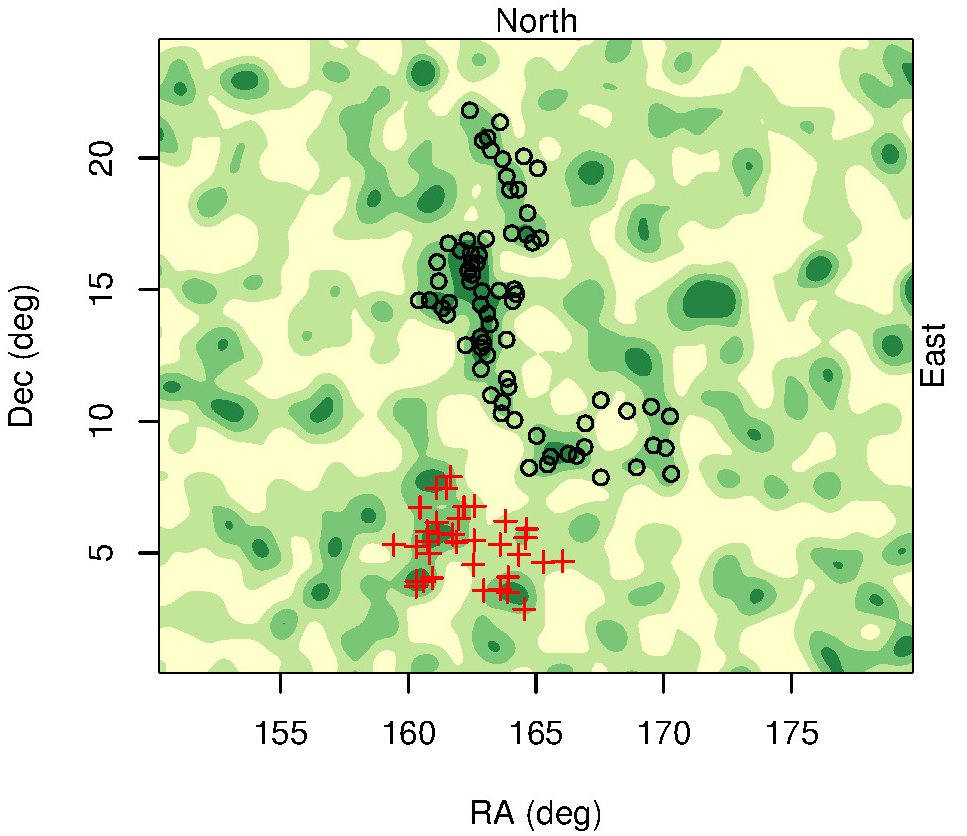

5. The Sloan Great Wall of Galaxies

When looking at the universe at large, we see that many galaxies (each generally containing billions of stars) tend to clump together, forming galaxy clusters. These clusters are, in turn, separated by stunningly large voids. We call these structures filaments, and boy, do we have many of them.

The image below depicts the structure of the filaments. Among them, one of the most massive is called “The Sloan Great Wall.” This structure is more than 1.38 billion light-years in length, and it’s located approximately one billion light-years from Earth.

The length is particularly impressive, as it makes up almost 1/60th (or about 5 percent) of the diameter of the observable universe (i.e., the part of it that can actually be detected — the actual universe is much larger than that).

Even more interesting is the fact that this region contradicts the very basis of modern cosmology, which relies on the universe being only 13.7 billion years old. Many noted physicists believe such a huge structure would take from 100 billion to 150 billion years to form to completion. To put it into a different light, if it took one week for the entire Earth to form, it would take more than two quintillion years for the Great Wall to form. Needless to say, it’s incomprehensibly large.

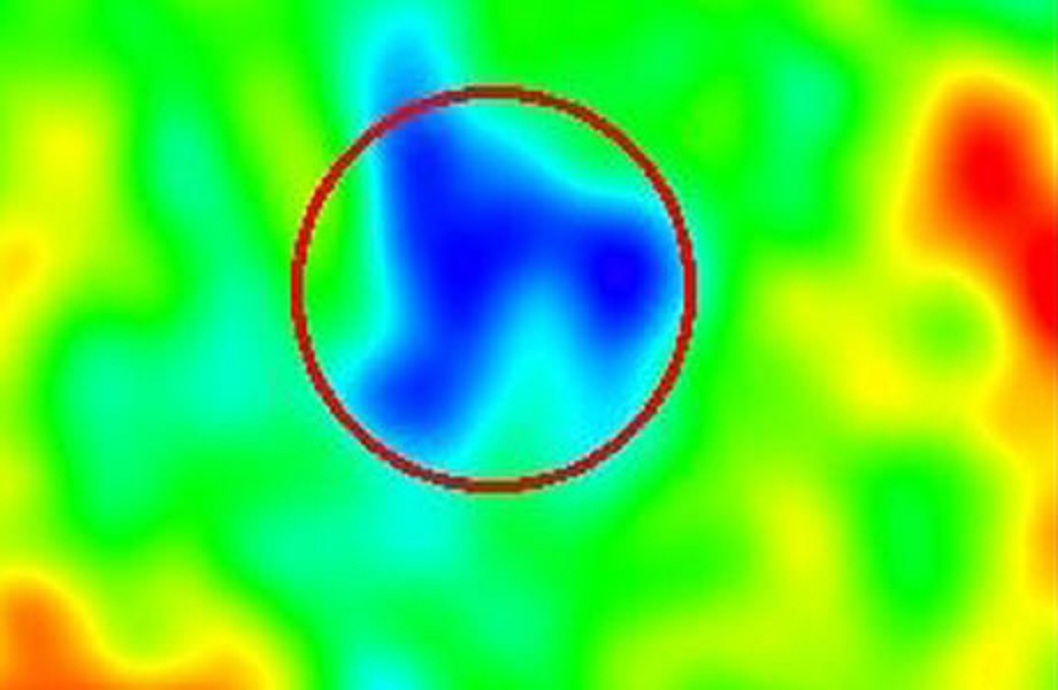

4. The Eridanus Supervoid

Most of us likely consider space to be empty. For the most part, it is. More than 99 percent of the universe is empty, and that doesn’t take into account how empty matter itself is. (Reminder: atoms are comprised mostly of empty space.) However, with the discovery of quantum physics, we know that even empty space is not really empty, but contains negligible amounts of gas, energy, and virtual particles, which pop in and out of existence.

So, it’s still rather surprising to find areas of space that are almost entirely devoid of all kinds of matter, including stars, planets, galaxies, clusters, interstellar materials, and even dark matter itself (the mysterious substance we can’t see directly, but that we know makes up a large portion of the universe’s overall mass).

The largest one of these voids can be found in the constellation Eridanus. It stretches over an area of space that is equal to one billion light-years. Many physicists have came up with some very interesting theories about the origin of this void. One of them postulates that it is an imprint of a parallel universe, which rubbed elbows with our own in the distant past. Another says that the region could be home to a universe-in-mass black hole.

3. Large Quasar Group

Next, we come to LQG (Large Quasar Group), the most massive structure in the known universe. This region of space is more than one billion light-years across, containing more than 73 active quasars (quasars are generally found surrounding active black holes, and some of them are capable of emitting more light and energy in mere moments than all of the stars in our galaxy can combined) in multiple galaxies.

This relatively new find is not only mindbogglingly large, but it also challenges some deeply held beliefs, primarily something we call the “cosmological principle.” It says that no matter where we look, the universe should be homogeneous on a macroscale (or, to put it simply, it should look the same everywhere).

Obviously, something this large (and unmatched in size) is problematic from a cosmological principle perspective. This is not the first, nor the last, find that proves we know much less than we think we know.

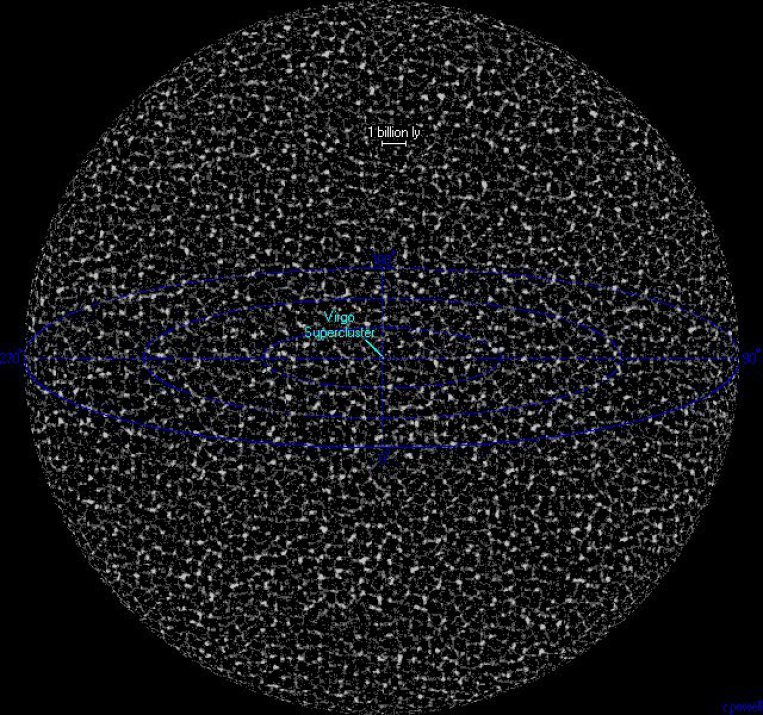

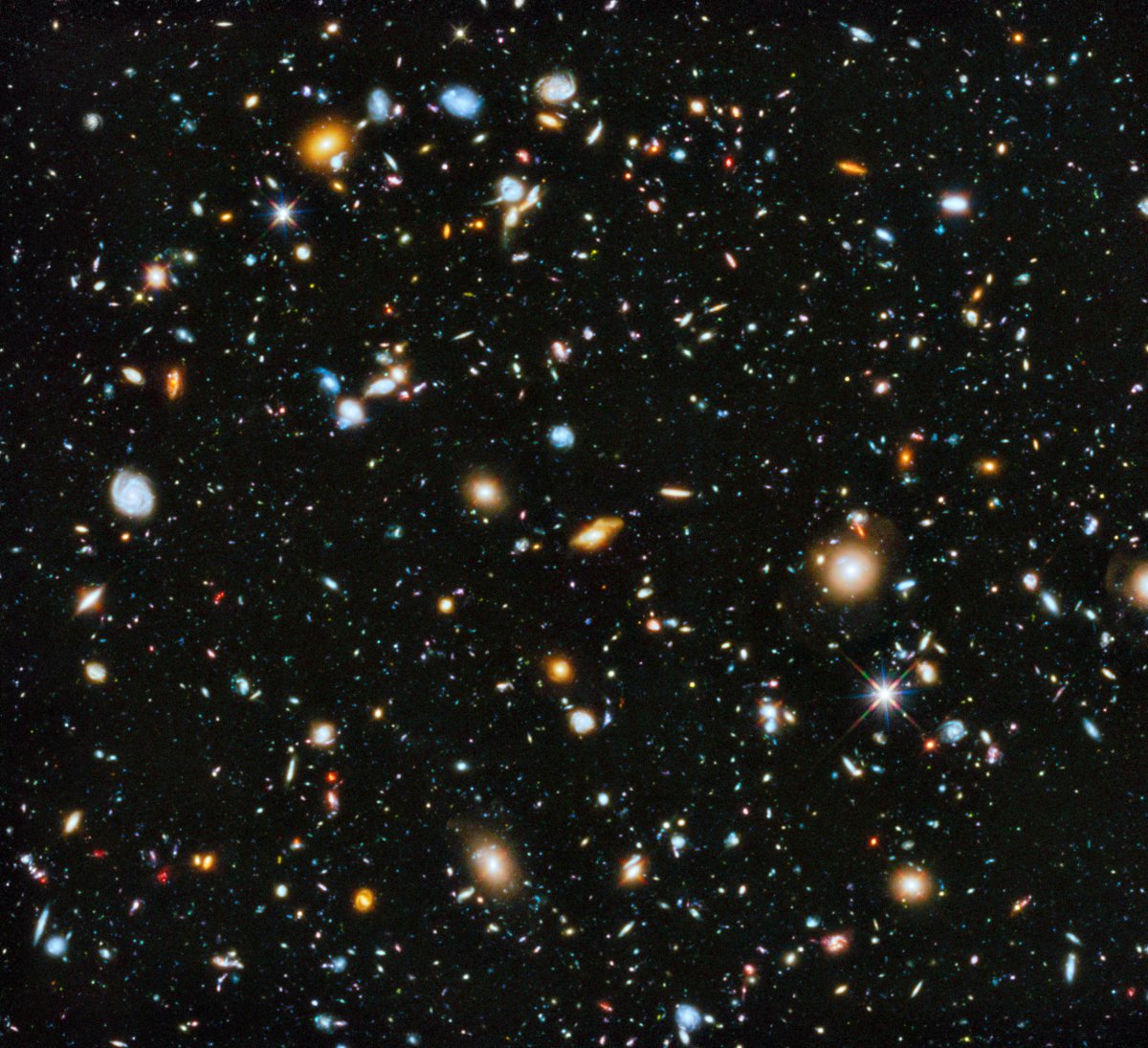

2. The Observable Universe

Now, we get to the super awesome, difficult to comprehend part of our list. The universe is basically divided into two parts. First, we have the observable universe, and then we have the actual universe. Both indeed qualify as structures, as you can clearly see the interconnectedness of the filaments and voids below.

We are seriously hindered by the laws of physics in terms of how much of the universe we can see. As we know, light generally travels at a constant speed while moving through the vacuum of space. Therefore, we cannot see the light from any object located beyond the “light horizon,” an area of space close enough for the light from these objects to reach us. This area has a radius of 13.7 billion light-years (the age of the universe).

Meanwhile, the actual universe has a diameter of a staggering 93 billion light-years. This is possible because after the Big Bang, when the universe was only a fraction of a second old, it began expanding at a very, very rapid rate, called “inflation.” This expansion continues on to this very day, albeit much more slowly.

To summarize, the observable universe contains an estimated 10 million super-clusters (a few of which we have discussed today), 350 billion large galaxies (such as the Milky Way), 25 billion galaxy groups, and 7 trillion dwarf (or satellite) galaxies with about 30 billion trillion stars. For the actual universe, those numbers could be much, much higher.

Which brings us to the last item on our list…

1. The Actual Universe

First, I must stress that we really have no idea how large the actual universe is. Many physicists believe that our universe is actually infinite in size (I won’t even go into the possibility of our universe belonging to a multiverse, with potentially an infinite number of universes), but the truth of the matter depends on the overall shape of spacetime.

Regardless, the actual universe is at least 14 trillion light-years in diameter (excluding some speculative factors). Try multiplying the estimated number of stars in each galaxy by the number of estimated galaxies in the universe, and you’ll get a rough estimate of the total number of stars the universe could contain. The numbers go into the septillionth digits, depending on your source.

Lets put that into perspective. In this scenario, each atom is composed mostly of empty space (about 99 percent) with one very tiny nucleus. Estimates (and a lot of complex mathematical equations) say that the actual universe could be ten billion times larger than the nucleus of an atom compared to the actual atom, with the nucleus representing the observable universe and the true universe being the rest of the atom.

The most unusual part? Due to the expansion of the universe (briefly mentioned earlier), there will come a time in the distant future when the observable portion of the universe begins to shrink before freezing and fading out of our view forever. Any light emitted from galaxies beyond this so-called “light horizon” (or the Hubble Volume, if you prefer) will be too far away and traveling too fast for the light to ever reach us.

So, yes, even though the universe is growing, it will eventually shrink (at least that’s how it will appear to living observers). The night sky will be dark, featureless, and devoid of all of its defining features. Not to worry, though. Long before that, our Sun will transition into a red giant, engulfing our planet and anyone unfortunate enough to still be living here. Enjoy your day!