EDITING HUMANS

Whether creating GM crops or making animals disease-resistant, gene-editing has always faced harsh criticism. One fear is how altering human DNA in embryos could recklessly create a fatal genetic disease that would exist for generations.

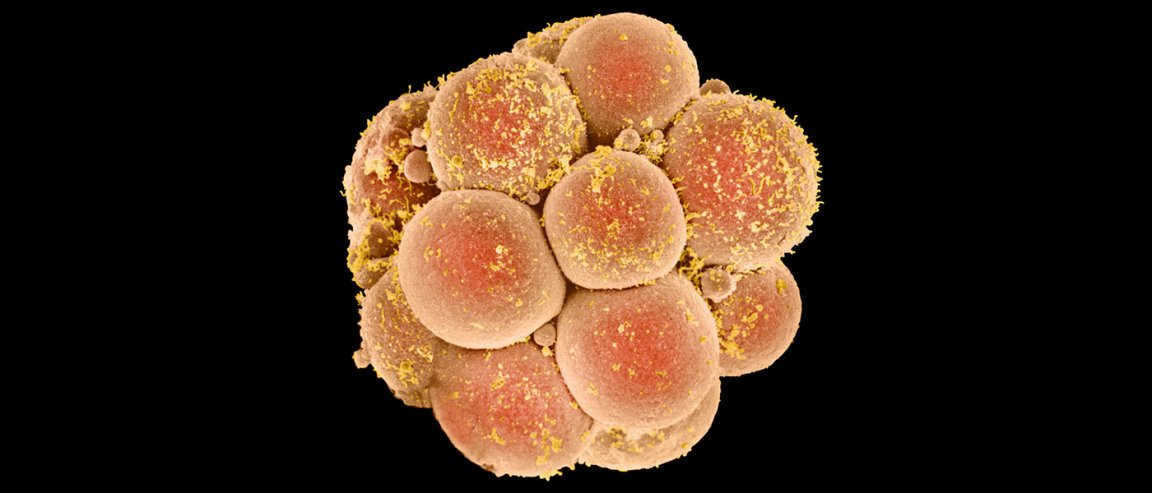

Despite this, one researcher is attempting the most controversial type of gene editing on earth. Developmental biologist Fredrik Lanner is the first researcher to ever modify the DNA of healthy human embryos.

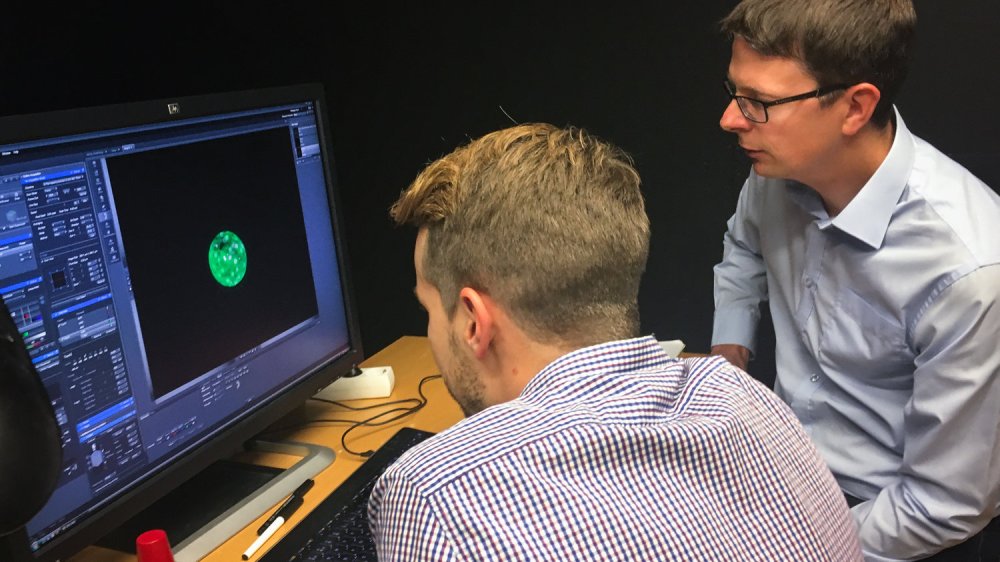

Lanner, who works at the Karolinska Institute in Stockholm, is editing genes in human embryos to see how they regulate early embryonic development. He’s specifically targeting genes crucial to normal embryonic growth to learn more about infertility, miscarriages, stem cells, and how to treat debilitating conditions.

“If we can understand how these early cells are regulated in the actual embryo, this knowledge will help us in the future to treat patients with diabetes, or Parkinson, or different types of blindness and other diseases,” Lanner told NPR.

He is using the popular CRISPR-Cas9 editing method. The tool utilizes two molecules that focus on your individual genes to make ultra-precise changes to your DNA.

“[Without CRISPR], we could not do this at all previously in the human embryo,” Lanner said. “The technology was just not efficient enough to try to look at individual gene function as the embryo develops.”

Lanner is also conducting basic research on how human gene editing could be done since the ethical debate has prevented many studies on how elementary gene-editing should work.

NOTHING TO FEAR?

A 2015 Chinese paper detailing the first human gene-editing experiment — despite not using healthy human embryos — sparked a firestorm of international debate. Global consensus has since banned the editing of human embryos that are intended to start a pregnancy.

But Lanner’s work falls under basic research, which is allowed. This kind of research could help establish the safeguards and limits that should be imposed on editing the human genome.

And Lanner calmed fears of his research leading to dangerous mutations in humans, noting how the embryos would only be observed for the first seven days and wouldn’t be able to develop past day 14.

He said he has no intention of helping create a world of designer babies — genetically modified children that many worry would constitute a society centered around biological superiority.

“It’s not a technology that should be taken lightly,” Lanner said. “So I really, of course, stand against any sort of thoughts that one should use this to design designer babies or enhance for aesthetic purposes.”