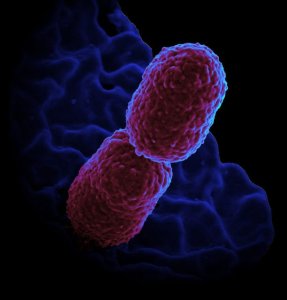

Resilient Bugger

The issue of superbugs that have incredible antibiotic resistance isn’t new. In 2016, the United Nations (UN) even elevated the problem of antibiotic resistance to crisis level, declaring it a “fundamental, long-term threat to human health, sustainable food production and development,” in the words of UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon.

The antibiotic resistance crisis and the growth of superbugs go hand in hand, obviously, and for the first time ever, the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has now issued a report about a patient dying from a superbug that’s immune to all 26 antibiotics available in the United States.

The report reads:

On August 25, 2016, the Washoe County Health District in Reno, Nevada, was notified of a patient at an acute care hospital with carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE) that was resistant to all available antimicrobial drugs. The specific CRE, Klebsiella pneumoniae, was isolated from a wound specimen collected on August 19, 2016. After CRE was identified, the patient was placed in a single room under contact precautions. The patient had a history of recent hospitalization outside the United States.

The patient was a 70-year-old woman previously hospitalized in India due to a fractured leg, which lead to an infection of the bone. The infection appeared to be resistant to the 26 antibiotics available in the U.S. Post-mortem analysis of the superbug, however, revealed that it was somewhat susceptible to fosfomycin, an antibiotic that isn’t approved in the U.S. for treatment of the patient’s type of infection.

The Path to Superbugs

So how did this superbug manage to become resistant to 26 types of antimicrobial drugs?

One possible way of developing resistance to certain or all antibiotics is through an exchange of bacterial plasmid — a loop-free floating DNA that bacteria can pass back and forth between each other. Say bacteria A is colistin resistant and it meets bacteria B in your gut, which is resistant to carbapanems. While these bacteria remain inactive, they can continue to exchange plasmids with other bacteria that you might get exposed to. The result is a pan-resistant superbug.

Perhaps even more troubling than this particular superbug’s resistance to all 26 antibiotics, though, is its particular resistance to one, colistin. Colistin is often considered the last-resort antibiotic, and resistance to it is usually caused by the mcr-1 gene. However, according to the CDC, “Because of a high minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) to colistin, the isolate was tested at CDC for the mcr-1 gene, which confers plasma-mediated resistance to colistin; the results were negative.” So not only was this superbug resistant to colistin, we don’t know why it was resistant.

The victim in the CDC’s report was kept in isolation during her hospital visit, and thus far, no one has observed any recurrences of this CRE bacteria in the other patients from the hospital. However, there’s no guarantee yet that this superbug is officially gone. Even if it is, other universally resistant superbugs are likely to emerge in the future. So is there anything that we can do at the moment to fight superbugs? Thankfully, a number of initiatives and studies are currently being worked on, so hopefully an alternative to current antibiotics will be found before one of these superbugs spreads significantly.