Cyanobacteria have been around for billions of years. They manufacture their own food through photosynthesis, absorbing solar light and turning it into energy. Much like plants, they release oxygen in the process, and their presence may have changed our atmosphere so much that bigger creatures could eventually breathe and thrive on Earth. Now, they’re being used to create tiny bio solar panels.

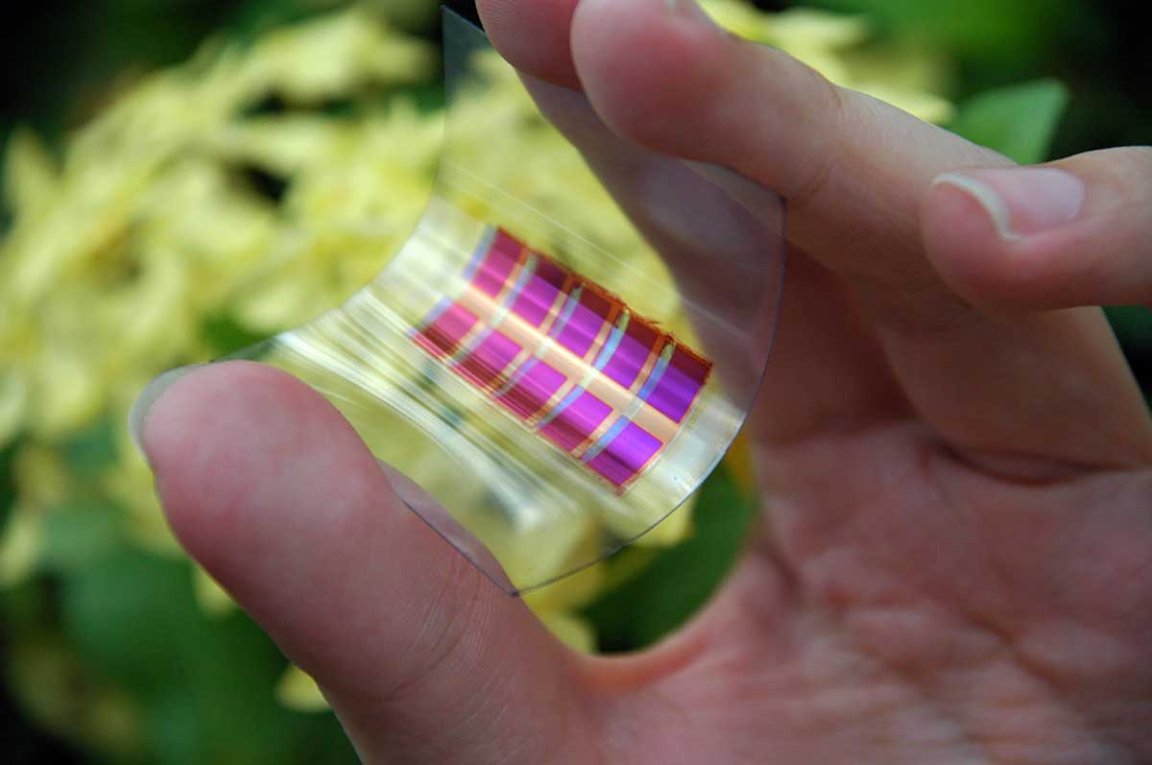

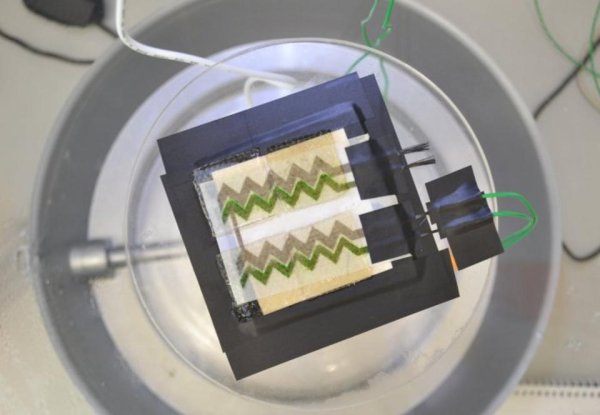

These tiny creatures have been used to create a living ink that can be printed on paper and work as bio-solar panels. Researchers at Imperial College London, the University of Cambridge and Central Saint Martins used an inkjet printer to draw precise patterns onto electrically conductive carbon nanotubes, which were also printed on the same surface.

Not only did the resilient bacteria survive the printing process, but produced a small amount of electricity that the team harvested over a period of 100 hours through photosynthesis.

This may seem to be a relatively short lifespan compared to the solar panels we install on our roofs, but “paper-based BPVs [microbial biophotoltaics] are not meant to replace conventional solar cell technology for large-scale power production,” Dr. Andrea Fantuzzi, co-author of the study (published in Nature) from the Department of Life Sciences at Imperial College London, said in a statement.

Instead, he explained, they could be used for small devices that require a small and finite amount of energy, such as environmental sensing and wearable biosensors. They are disposable and biodegradable, and they also work in the dark, releasing electricity from molecules produced in the light.

“Imagine a paper-based, disposable environmental sensor disguised as wallpaper, which could monitor air quality in the home. When it has done its job it could be removed and left to biodegrade in the garden without any impact on the environment,” Dr. Marin Sawa, a co-author from the Department of Chemical Engineering at Imperial College London, said in a statement.

According to Fantuzzi, the paper-based bio solar panels could be integrated with biosensor technology to monitor health indicators, such as blood glucose level in patients with diabetes. He said that because the new technology is so cost effective, it could “pave the way for its use in developing countries with limited healthcare budgets and strains on resources.”

Hazel Assender, Associate Professor at the Department of Materials with the University of Oxford in the UK, told Futurism: “Using bacteria opens up new possibilities [in the field of sensing], but the challenge, as so often, will be selectivity: what is it about the ‘atmosphere’ that such a sensor might monitor, and how will it react to all the other environmental changes?”

The team agrees that the discovery is, however exciting, just a proof of concept for now, and the next challenge is to make panels that are more powerful and long-lasting. The current bio solar panel unit is small, the size of a palm, and the researchers are confident that it could be scaled up to the size of an A4 sheet of paper.