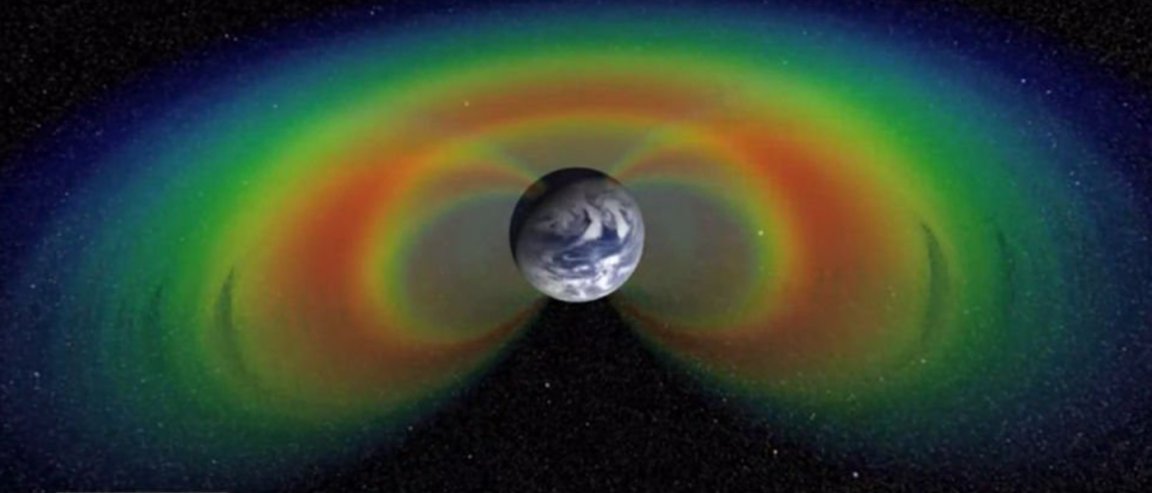

A Radiation Belt

Massive bands of radiation, known as the Van Allen Belts, surround Earth. Discovered in 1958, these belts of charged particles are routinely monitored by the Van Allen Probes. However, because of the previously perceived danger of these belts, scientists have been wary of sending spacecraft to conduct further studies of them. But new observations from the probes have shown that what we’ve thought about these belts might not be true.

Recent findings have shown that the particles that astronomers thought made the inner belt so dangerous — namely, the ultra-fast (relativistic), highest-energy s — aren’t usually even present.

That’s right — the area that was thought to contain destructive electrons circling 640 to 9,600 km (400 to 6,000 miles) above the surface of Earth is typically (more often than not) entirely devoid of these electrons. It is now known that especially intense solar storms sometimes push high-energy electrons into the inner belt. While these instances are the exception to the rule, the belt takes a while to return to “normal,” so it was thought that the electrons were a usual fixture.

So, how did they figure this out? What technology could have been used with the probe to determine this new information? Well, it turns out that they used a specialized instrument called the Magnetic Electron and Ion Spectrometer (MagEIS). This device allowed scientists to more easily determine the energy and charge of different particles. This allowed them to distinguish between relativistic electrons and high-energy s. Seth Claudepierre, a Van Allen Probes scientist, said in a NASA press release that subtracting these protons from the measurements was key to these findings.

“We’ve known for a long time that there are these really energetic protons in there, which can contaminate the measurements, but we’ve never had a good way to remove them from the measurements until now,” Claudepierre.

A New Frontier

They have also found that not only is the inner belt a lot “weaker,” as some might put it, than previously thought, it is also much less stable. It is expected for the outer belt to fluctuate in size in response to solar activity, but now astronomers can see that the inner belt acts similarly.

The inner belt is no longer known as an unchanging band of high-energy, relativistic electrons. It has now been revealed to be an ever-changing belt that is (usually) made up of low-energy electrons and high-energy protons.

Because of the previous notions surrounding these belts, there has been relatively little study of them. This new information opens up an entirely new door for discovery. As we continue to explore our solar system, new information about these belts and the ways in which solar winds, Earth’s magnetic field, and radiation interact could be invaluable. Especially as scientists consider the possibilities of terraforming Mars, a planet lacking an atmosphere, research of the Van Allen Belts could catapult progress forward.