A crewed mission to Mars is still many years out — if not decades.

But as rocket technology makes massive strides, scientists are starting to wonder what the best way to get there could be. And one new idea, Space.com reports, involves a side trip to another of our star system’s planetary bodies.

To make visits to the Red Planet cheaper and faster, scientists are arguing that making a Venus flyby could make a lot of sense.

In a white paper penned by a team led by John Hopkins planetary geologist Noam Izenberg, the researchers argue that Venus flybys not only “provide opportunities to practice deep space human operations,” but “offer numerous safe-return-to-Earth options” as well.

“There’s science at two planets for much less than the price of two separate crewed missions,” Paul Byrne, a planetary geologist at North Carolina State University, who worked on the paper, told Space.com.

Broadly speaking, there are two ways to get to Mars and back: either you go when Earth and Mars orbits align, something that only occurs every 26 months, and wait until the planets align again for the return. As Space.com points out, that means astronauts could be trapped on Mars for as much as a year and a half.

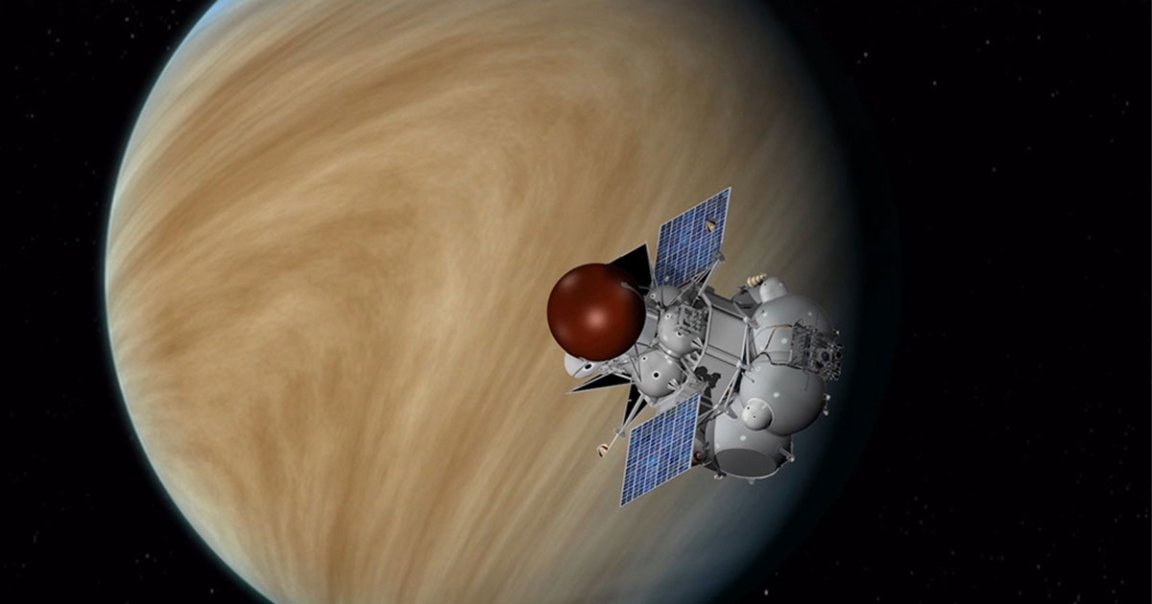

The other method is to use Venus slingshot to whip a spacecraft using gravitational forces, a process that could end up significantly reducing the amount of fuel needed to get to Mars.

There are plenty of other advantages to this approach as well. Such a trip could be made every 19 months and allow for much shorter stays, down to just a month. It could also allow for much quicker and simpler emergency returns back to Earth if something were to go wrong.

It’s a two-birds-with-one-stone approach — the scientists are also excited at the prospect of getting a better look at Venus during the approach.

Thanks to its proximity and lower lag, astronauts in the vicinity of Venus could even “control rovers on the surface and aircraft in the atmosphere in real time with a virtual reality headset and a joystick,” John Hopkins planetary geomorphologist Kirby Runyon, who worked on the white paper with Izenberg, told Space.com.

But there is a small drawback: The actual journey could take quite a bit longer, and solar radiation could pose more of a threat to astronauts’ health thanks to Venus’ close proximity to the Sun.