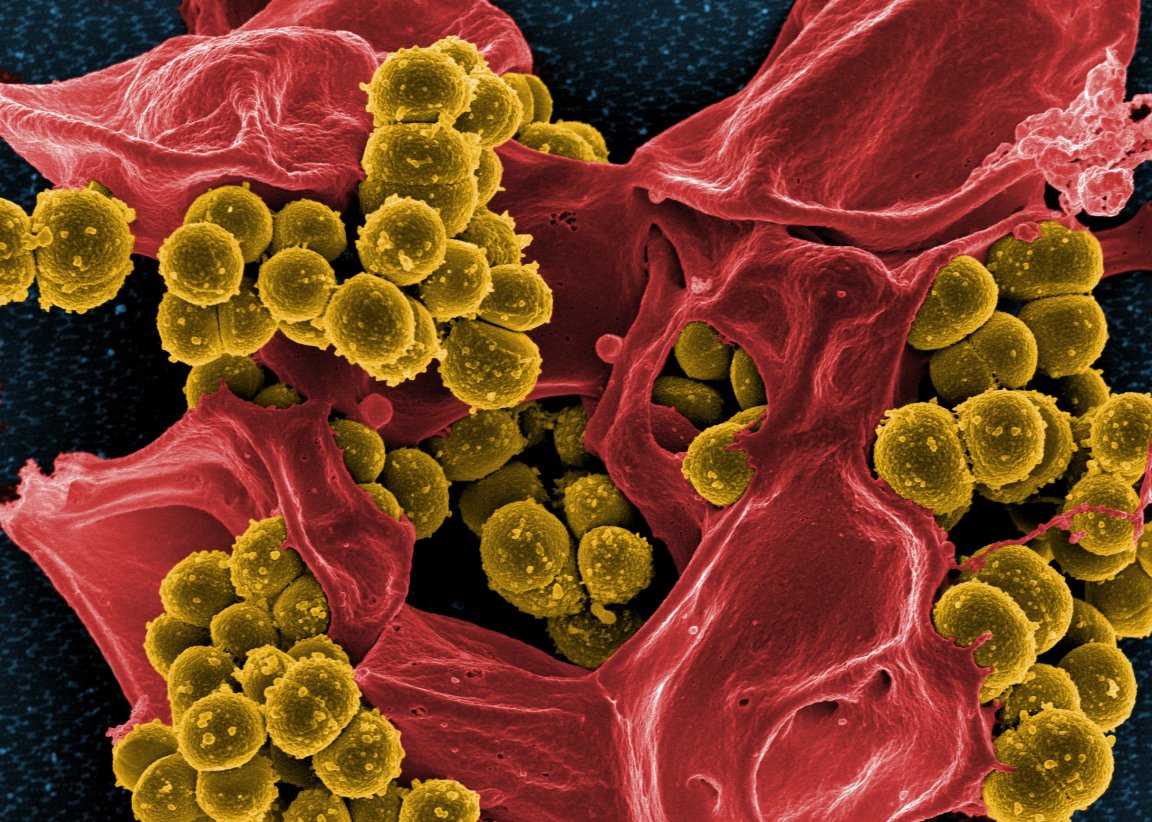

Drug-Resistant Superbugs

Antibiotic resistance is one of the main threats to public health of our time. While superbugs are emerging all over the world thanks to an overuse of existing antibiotics, particularly in agriculture and farming, new drugs able to fight increasingly potent infections are hard to come by.

To break this deadlock, researchers have been turning to synthetic molecules, which unlike common antibiotics can fight off infections without leading to drug resistance. Scientists at IBM Research, the world’s largest industrial research organization, have come up with a synthetic molecule that works as a last ditch effort against superbugs that have already spread to every organ in the body, travelling through the blood. Their findings are detailed in a new study published in the journal Nature Communications.

Synthetic molecules, as the name implies, are lab designed and developed polymers, chemicals made of large molecules comprising smaller, simpler molecules. To be used as an antibiotic, a synthetic molecule has to meet certain conditions: It has to be biodegradable and able to effectively attack bacteria without endangering other organs in the body.

Usually, the immune system attacks bacteria by destroying their protective membranes, and IBM’s synthetic molecule had been designed to work the same way. “We are trying to emulate the exact way that our innate immune system works,” lead author James Hedrick explained to Popular Science. “When you get an infection, right away your body secretes antimicrobial peptides, which is simply a fancy word for a polymer.”

Works Better Than the Real Thing

The IBM research isn’t the first to explore the potential of synthetic molecules in fighting antibiotic resistance. One previous study focused on using synthetic molecules to prevent the genes carrying resistance properties from being transmitted between bacteria. Others use synthetic molecules as antibiotics that cause bacteria to explode, but researchers acknowledge that this is dangerous because it would help spread toxins in the bloodstream.

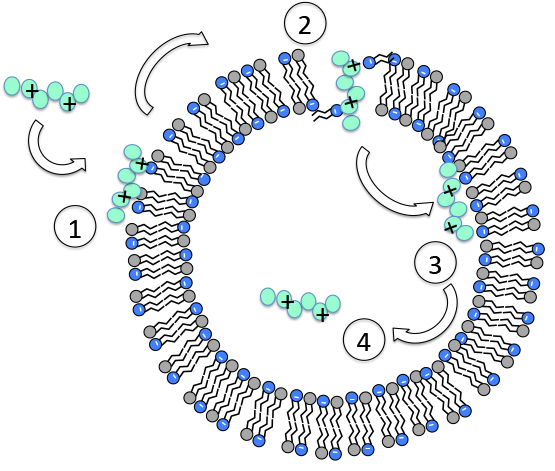

To minimize these side effects, IBM’s synthetic molecule works by killing the bacteria from the inside out. “First, the polymer binds specifically to the bacterial cell,” Hedrick wrote in an IBM Research blog. “Then, the polymer is transported across the bacterial cell membrane into the cytoplasm, where it causes precipitation of the cell contents (proteins and genes), resulting in cell death.”

The molecules latch on to the bacteria using electrostatic charges to attach to various parts of their surface. So, even when a bacterium undergoes changes in its internal make-up, the synthetic polymers is still able to identify it.

The molecule is also able to completely degrade after three days. “It basically just comes in, kills the bacteria, degrades, and leaves,” Hedrick told Popular Science, adding that this approach could also mitigate antibiotic resistance or work against extremely resistant strains even when the bacteria has evolved.

So far, the IBM researchers have successfully tested their synthetic molecule on mice infected with five difficult-to-treat, multi-drug resistant superbugs that can be commonly acquired in hospitals and often lead to sepsis or even death. The plan is to eventually have the synthetic molecule ready for human clinical tests.

This research adds to the range of creative ideas scientists have come up with to stave off the worst impacts of the drug resistance crisis, including developing “super enzymes” to synthetic nanobots. Unfortunately, lab-produced molecules don’t come by as cheap as natural ones. For now, our best bet remains to always follow the doctor’s instructions and only use antibiotics only when we truly need them.