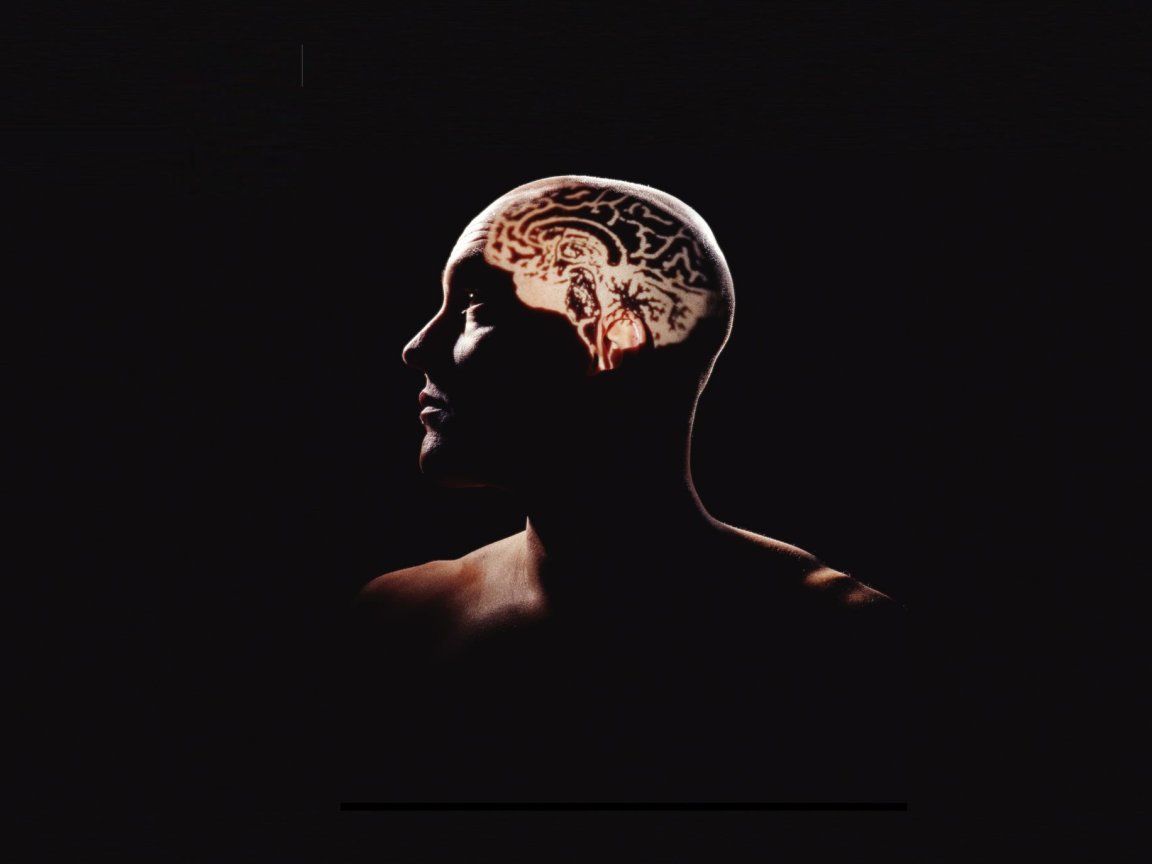

Physical Roots of Depression

Although current treatments for depression mostly focus on brain chemicals such as serotonin, scientists now think inflammation throughout the entire body (triggered by an overactive immune system) may be the root cause of the problem. Widespread inflammation, they posit, could be producing feelings of unhappiness, hopelessness, and fatigue. If so, depression may be treatable with anti-inflammatory drugs. It may also be a symptom: much like the low spirits experienced by many people when they are ill and their immune system is busy fighting infection or viruses. In the case of chronic depression, the immune system may be failing to “switch off” after an illness or trauma, leading to persistent symptoms.

A growing body of research, including scientific papers and results from clinical trials, appears to be revealing a connection between treating inflammation and alleviating depression. In late July 2017, Stanford researchers revealed that they could create a diagnostic laboratory test for myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS), along with what may be a world-first treatment. This work confirmed and built on prior work connecting ME/CFS — a disease which is often associated with depression — and inflammation.

In October 2016, a major review of research on the next generation anti-inflammatory drugs (most often used to treat autoimmune disorders) revealed a definitive link between inflammation and depression. This link could present a promising new avenue of treatment. The work showed that about one-third of people with depression have higher levels of cytokines, proteins that control the way the immune system reacts. This could indicate inflammation in their brains. It also revealed that people with “overactive” immune systems are more likely to develop depression.

Immuno-Neurology

University of Cambridge Head of the Department of Psychiatry Professor Ed Bullmore told The Telegraph that he thinks a new field of “immuno-neurology” is coming soon. “It’s pretty clear that inflammation can cause depression,” Bullmore said at a London briefing connected to the recent Academy of Medical Sciences FORUM annual lecture. “In relation to mood, beyond reasonable doubt, there is a very robust association between inflammation and depressive symptoms. The question is does the inflammation drive the depression or vice versa or is it just a coincidence? In experimental medicine studies if you treat a healthy individual with an inflammatory drug, like interferon, a substantial percentage of those people will become depressed. So we think there is good enough evidence for a causal effect.”

One important result that could arise from this work would be more effective treatments for depression; treatments that may not need to be lifelong. Another major implication is that, should this knowledge shape the norm for understanding and treating depression, the artificial dichotomy between body and mind could be forever altered. Socially, viewing depression as a condition with a definite physical cause could also help reduce the stigma around mental illness that often prevents many from getting treatment.