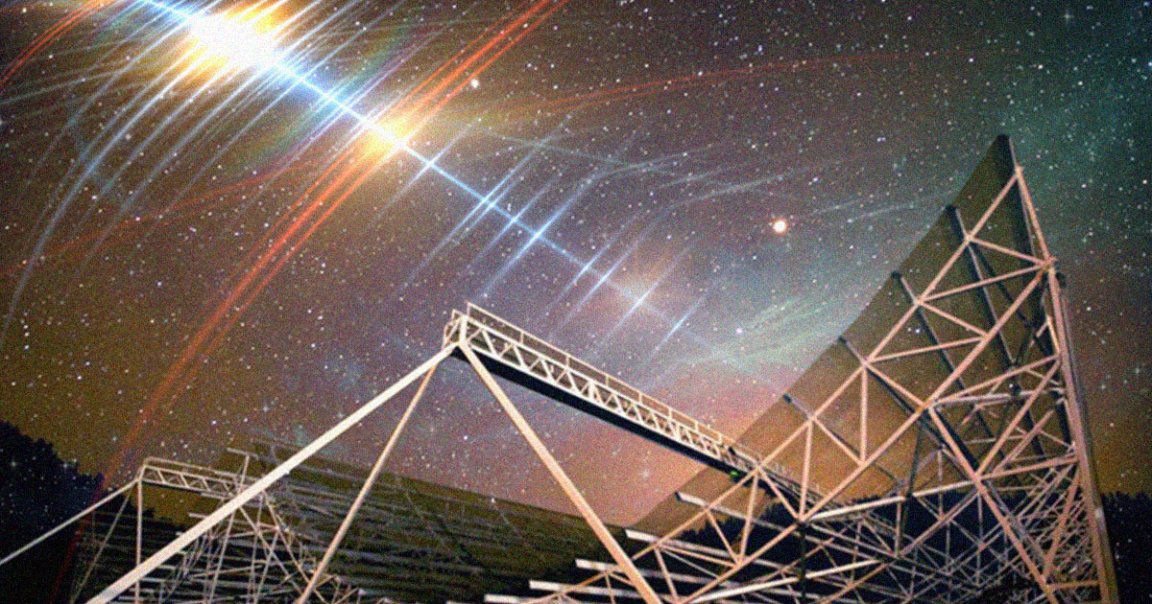

Astronomers have identified a mysterious new fast radio burst (FRB) that beats at regular intervals, much like a heart.

The signal, dubbed FRB 20191221A, is the longest-lasting FRB ever discovered and has a clear periodic pattern, repeating every 0.2 seconds for up to three seconds. That’s about 1,000 times longer than other signals like it, according to a statement.

FRBs have puzzled astronomers ever since the first was discovered back in 2007. The mysterious flashes are extremely bright and powerful, releasing copious amounts of energy for a short period.

While we’re arguably getting closer to understanding what they are and where they came from, discoveries like this latest one are only leading to more questions.

FRB 20191221A emanated from a galaxy several billion light-years away from us. The signal caught astronomers’ eye because it was both “very long, lasting about three seconds” and featured “periodic peaks that were remarkably precise, emitting every fraction of a second — boom, boom, boom — like a heartbeat,” as Daniele Michilli, an astronomy postdoc at MIT and coauthor of a new paper about the finding published in the journal Nature, explained in the statement.

“This is the first time the signal itself is periodic,” he added.

Its source may still be a mystery, but astronomers are starting to hone in on an answer: the signal, like many other FRBs out there, may have emanated from a magnetar, the highly energetic and spinning remains of a collapsed star.

“There are not many things in the universe that emit strictly periodic signals,” said Michilli in the statement. “Examples that we know of in our own galaxy are radio pulsars and magnetars, which rotate and produce a beamed emission similar to a lighthouse,” he explained. “And we think this new signal could be a magnetar or pulsar on steroids.”

There’s one big difference, though: the newly discovered signal is a million times brighter than the neutron stars we’ve discovered so far.

“From the properties of this new signal, we can say that around this source, there’s a cloud of plasma that must be extremely turbulent,” Michilli explained.

The researcher and his colleagues are now hoping to use FRB 20191221A’s regular beats as a way to measure the rate of the expansion of the universe, a fascinating use case for the data the team has been collecting.

“This detection raises the question of what could cause this extreme signal that we’ve never seen before, and how can we use this signal to study the universe,” Michilli said, adding that he hopes future telescopes could be used to “discover thousands of FRBs a month” that could bring us closer to some much-needed answers.

READ MORE: Astronomers detect a radio “heartbeat” billions of light-years from Earth [MIT]

More on FRBs: Planets Scream as They’re Ripped Apart, Scientists Say