If Jupiter is renowned for one thing besides its gargantuan size, it would have to be its spectacular storms. The storms brewing within Jupiter’s upper-atmosphere pale in comparison to even the most deadly storms on Earth, yet none of them can hold a candle to Jupiter’s most volatile storm, called the “Great Red Spot.”

The storm was initially found by Giovanni Cassini (if that name sounds familiar, it should. After all, the Cassini-Huygens probe was partially named after him) some 400 years ago; long before we had uber-sophisticated telescopes and space-based technologies. Even then, he could tell that this region was significant in some way; an assertion that wasn’t proven until we dispatched the very first probes into the outer solar system. Once they arrived within the vicinity of Jupiter, they returned a treasure trove of useful information about the planet, some of its moons, and, of course, its (now) most famous storm.

Today, we now know that this swirling vortex gets its fantastical red color from a number of complex organic molecules—including red phosphorus and sulfur—that have collected within the clouds that comprise Jupiter’s atmosphere. These same clouds birthed the storm itself, which, at one point, could have engulfed Earth three times over (it once extended 8,000 miles [20,000 km] across, and about 12,400 miles [14,000 km] wide), with winds churning at speeds exceeding 400 miles (640 km) per hour (For perspective, if something like this appeared on Earth, it would essentially qualify as a class 20 hurricane. Needless to say, we should be thankful Earth is as serene as it is most of the time).

The Great Shrinking Storm:

No one can say with certainty how long the storm has been brewing, but we can definitely say that the storm will eventually dissipate into nothing (after all, nothing lasts forever—not even the universe). In fact, observations made over the last century have revealed that the storm has more than halved in size. The first recorded observation, taken in the late 19th century, showed that the storm was more than 25,476 miles (41, 000 kilometers) wide.

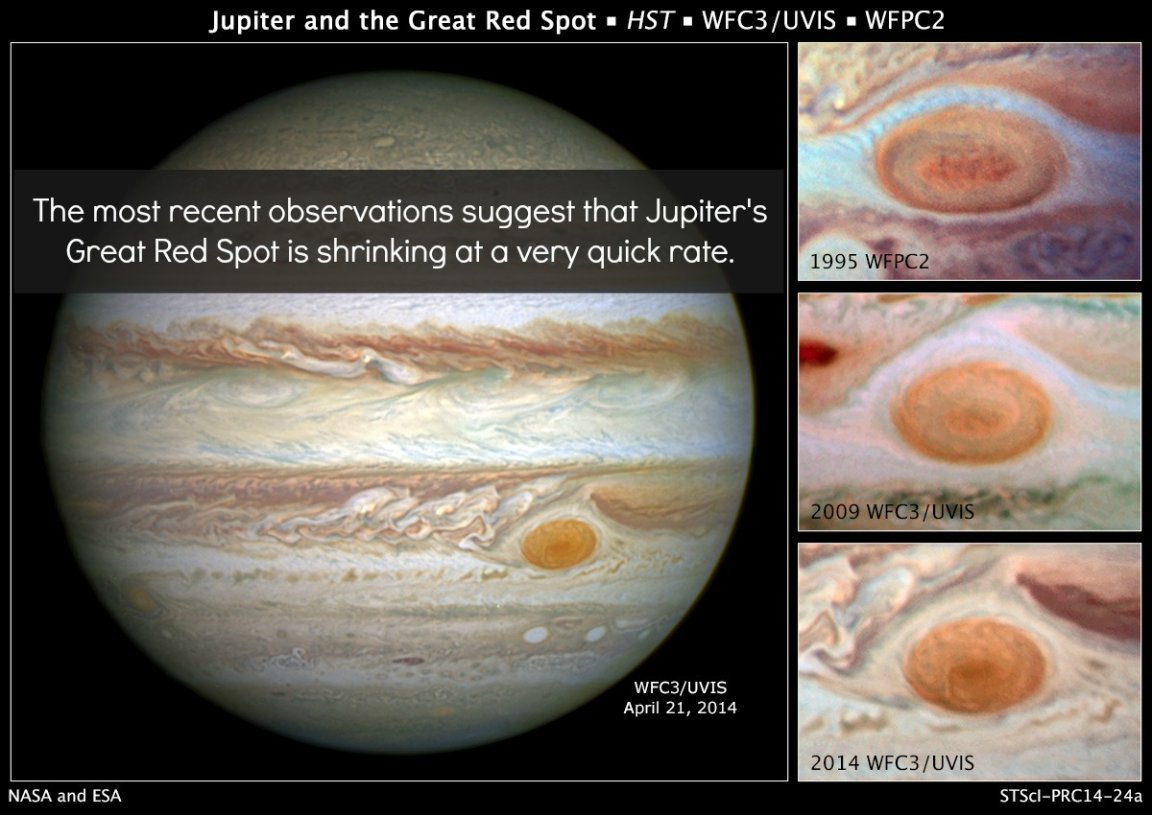

The first up-close observations—undertaken by the Voyager probes in 1979 and 1980, respectively—then revealed that its size continues to noticeably dwindle each subsequent time we look at it.

In the most recent portrait, the storm has shrunken to the point that its structure no longer resembles a circle, but an oval, with it extending a mere 10,250 miles (16,100 kilometers) across. Putting those size numbers in with other measurements, we see that it appears to be shrinking 621 miles (1,000 kilometers) each year.

What is Happening Here?

Astronomers are uncertain why the storm keeps shrinking in size at such a steady rate. If it continues, the storm could disappear completely in 17 years, which would make Jupiter a little less spectacular. Perhaps an answer will come when Juno reaches the Jovian planet in 2016. Mission objectives include studying Jupiter’s atmosphere, magnetosphere, gravity field and its composition.

The image below charts the decline of the great red spot over a period of twenty years. According to NASA, “Historic observations as far back as the late 1800s gauged the storm to be as large as 25,500 miles on its long axis. NASA Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 flybys of Jupiter in 1979 measured it to be 14,500 miles across. In 1995, a Hubble photo showed the long axis of the spot at an estimated 13,020 miles across. And in a 2009 photo, it was measured at 11,130 miles across.”

One hypothesis suggests that small eddies surrounding the storm are feeding it, while siphoning some of its strength. They would also be disturbing the inner mechanisms within Jupiter that allow the storm to remain intact. Either way.. one can hope that the process halts before it is too late. It would be a travesty to lose one of our solar system’s most interesting features.

Plus, it IS Jupiter’s most significant claim to fame.

Read more about Jupiter’s composition here, or find out what it would be like to spend a day in Jupiter’s “Great Red Spot.“ Jupiter might also host liquid oceans deep beneath its clouds.