Source: Historical museum of Bern via Sandstein

Throughout history, Homo Sapiens (as well as our direct ancestors like Neanderthals and Australopithecus) have attempted to breakaway from nature; one of the many ties that bind us. Instead of being controlled by the whims of mother Earth and adapting to our environment, we try and make nature and our environment adapt to us. We have invented a great variety of tools in order to assist us in this capacity. Over time, humans even started to harness nature itself–raising plants and animals for food rather than gathering or hunting. There is little doubt that, for the most part, present day Homo Sapiens dominate nature.

Of course, we can debate the ways in which this practice is both beneficial and problematic, but such debates are for philosophers. Scientists are more concerned with how humans became so technologically efficient and how they ultimately came to dominate other species. Of course, many variables play a role in the Human’s rise to power, but the primary determining factor is what we call intelligence.

But there’s more to intelligence than meets the eye.

What is Intelligence?

Intelligence is really a rather ambiguous term. We often debate what it means, how it should be defined, and if it’s specific to Humans. As such, I will start off with a broad definition. Dr. C. George Boeree of Shippensburg University describes intelligence as a person’s ability to learn and understand information, apply that information to solve problems, and engage in abstract reasoning. This definition is good, but it seems to be a little lacking. And as it turns out, Einstein has something to contribute to this conversation. In With Other Opinions and Aphorisms, he writes “Imagination is more important than knowledge. For knowledge is limited, whereas imagination embraces the entire world, stimulating progress, giving birth to evolution. It is, strictly speaking, a real factor in scientific research.”

Regardless of the formal definition, the way we classify intelligence is extremely subjective. For example, person “A” might view a crow as a very intelligent creature because it demonstrates problem solving skills, while person “B” sees the bird as being unintelligent because its learning curve is so slow. Similarly, one could call Beethoven intelligent for his composing abilities, or assert that he is merely musically inclined. So you see, measuring intelligence has always been an issue among psychologists because there are so many factors (critical thinking problem solving…the list goes on and on). And there’s still no consensus as to what should be measured when talking about intelligence. The best thing we can come up with are IQ tests.

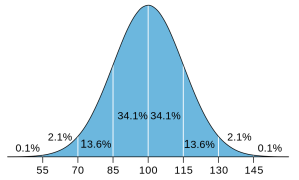

IQ (intelligence quotient) tests are one of the most popular ways to measure a person’s intelligence (though these tests vary nearly as much as the very definition of intelligence). IQ tests are tests in which you cannot study, this means that the test measures the general intellect of a person at any age. To do this, researchers in the early 1900s developed a concept known as “Mental age” vs “chronological age.” The rational is as follows, if a child is six years old, but can only perform tasks as well as a three year old, that child is said to have a “mental age” of three years. One then takes the “mental age” and divides that by the child’s “chronological age” to determine a “mental quotient.” The six year old child performing at a three year old’s rate would be said to have a mental quotient of .5 (three divided by six), This number is now multiplied by 100 to get rid of the decimal, so we end up with an IQ of 50.

Image via: Dmcq of Wikipedia

This seems like a silly abstract measurement, which is why scientists developed many types of standardized tests for IQ, trying to reduce the subjective and unscientific nature the measurement. Modern IQ tests often measure a person’s ability in a few distinct areas: Spatial ability (visualizing shapes and figures), Mathematical ability (using logic to solve problems), Language ability (solving word puzzles or recognizing words with jumbled letters etc.), and Memory (recalling visual or aural information). These subjects are chosen because they are said to measure “general intelligence,” which boils down to the ability to understand concepts rather than have previous knowledge of concepts. A breakdown of IQ scores can be found here.

IQ tests cannot accurately measure every aspect of a person’s brilliance (or lack thereof), and results can even vary from test to test (it’s worth noting that only professional, peer reviewed tests are accurate/accepted. Online IQ tests are just “for fun”). In recent years there have been many EQ (emotional intelligence quotient) tests that attempt to measure a person’s ability to identify, control, and assess emotion in others and themselves. These tests have not been widely accepted as useful, and in no way replace current IQ testing – but they are perhaps another way to measure a person’s mental faculty.

While IQ is often held as a steadfast measure of a person’s ability to perform academic tasks, that’s not the whole story. There are many other untested variables that contribute to a person’s intelligence–learning style, personality, mood–all of these things can impact intelligence and can sway the results of our cherished IQ tests.

In part two of this article, I will attempt to blow IQ out of the water, armed with recent research, the notion of Intelligence may be changing for the better – Changing from an oppressive statistic to an uplifting challenge for those who wish to become great.