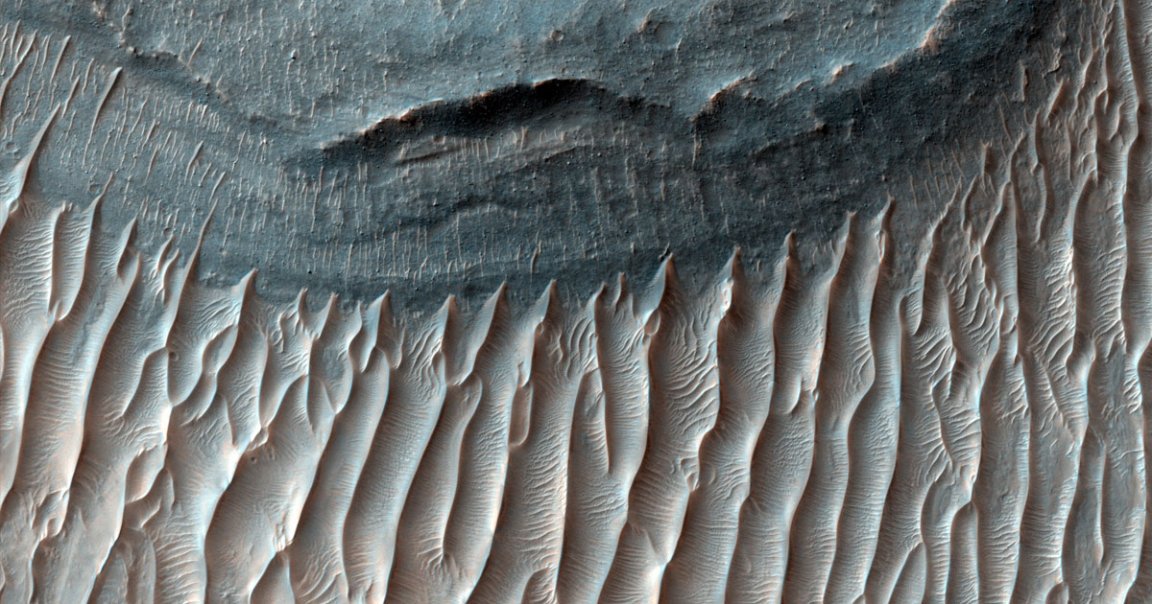

Researchers have found evidence of gigantic waves of sand, often referred to as “megaripples,” slowly moving around on the surface of Mars, as Science reports.

Megaripples aren’t unique to Mars; they can be found in deserts back here on Earth as well. But the Red Planet’s colossal sand dunes, believed to have formed hundreds of thousands of years ago, could be a sign that winds on Mars are even stronger than previously believed.

In a paper published last month in the Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets, the team suggests that megaripples may be migrating thanks to small grains of sand knocking into larger grains, dragging them into motion.

The new research goes against current atmospheric models that largely suggest winds couldn’t be strong on Mars enough to move these mega sand structures. In other words, a thin atmosphere may allow for surprisingly strong winds.

Using images taken by NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter, the international team of scientists had a closer look. By focusing on two sites near the Martian equator, they analyzed a total of 1,100 megaripples.

Scientists previously believed that these megaripples on the Red Planet were first formed a long time ago, when a thicker atmosphere allowed for much heavier winds, and were now stationary.

But to their astonishment, they found that the megaripples do in fact appear to move — albeit at the slow pace of roughly 10 centimeters per Earth year. According to Science, that’s about as fast as megaripples in the Lut Desert in Iran.

The surprising takeaway: Winds could be strong enough after all, despite the thin Martian atmosphere. “A past climate with a denser atmosphere is not necessary to explain their accumulation and migration,” the team concluded in their paper.

And that’s bad news for future astronauts visiting the Red Planet, as windy conditions could end up messing with habitats and solar panels.

Nonetheless, it’s an astonishing new discovery about our planetary neighbor.

“We can now measure processes on the surface of another planet that are just a couple times faster than our hair grows,” Ralph Lorenz, a planetary scientist at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory, who was not involved in the study, told Science.

READ MORE: Giant waves of sand are moving on Mars [Science]

More on Mars: NASA’s Next Rover Will Bring First-Ever Microphone to Mars