Deadly Parasites

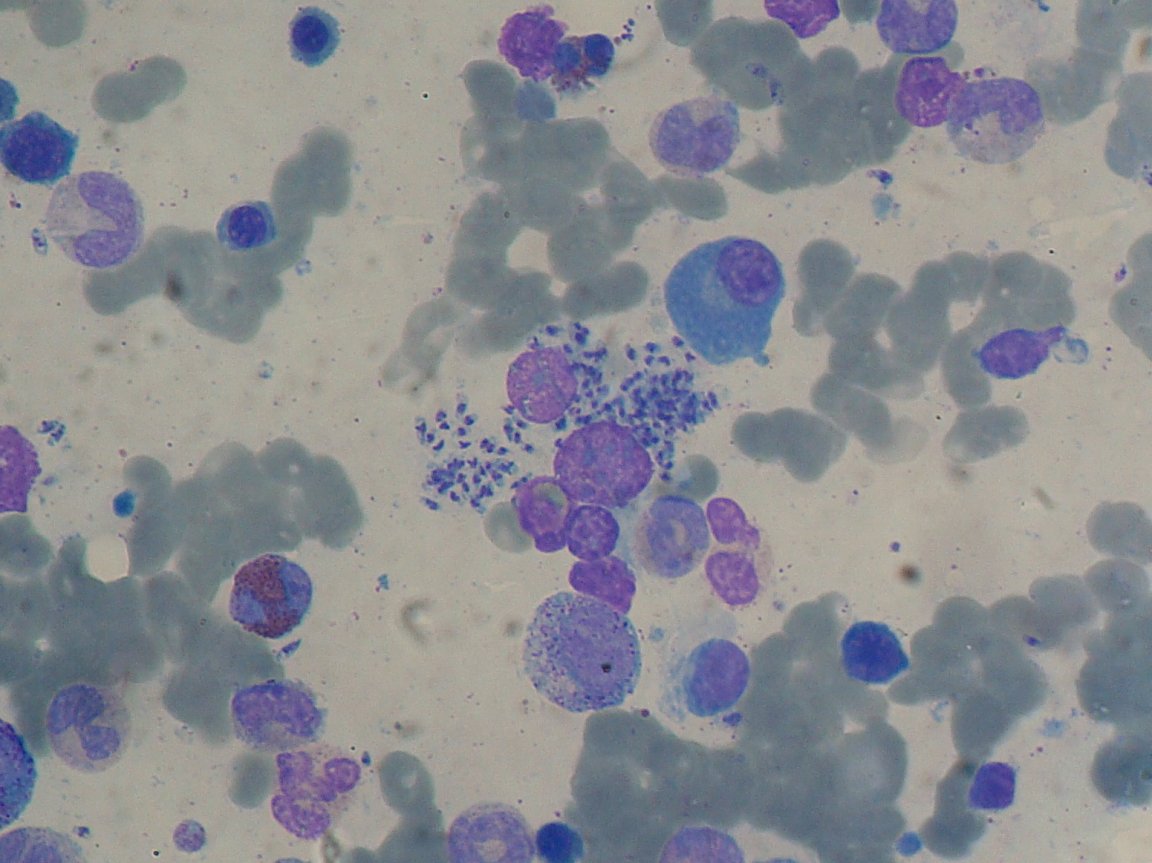

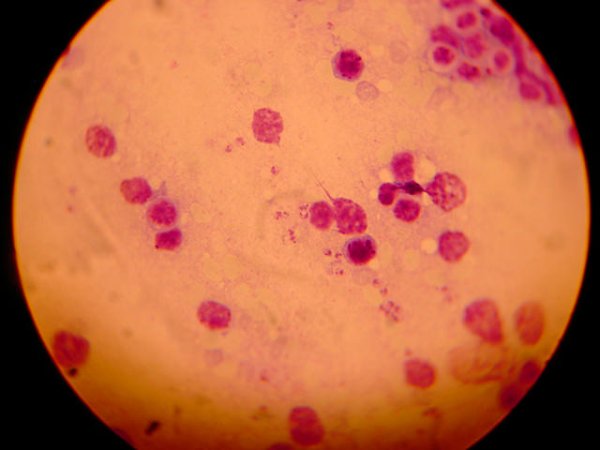

The 30 known strains of Leishmania are the second-deadliest parasites in the world. Once inside the human body, they cause infections that eat away at the face, ulcerate the skin with huge boils, and can fatally mutilate the liver and spleen. These frightening parasites — second only to malaria in terms of fatal impact worldwide — are slowly edging closer to the southern border of the United States.

There is no vaccine against Leishmania yet, but new research shows scientists are on the cusp of creating one. A new experimental vaccine, created using a proprietary biological particle, has enabled the immune systems of laboratory mice (systems that were genetically altered to mimic those of humans) to withstand Leishmania.

Those who contract Leishmania may develop leishmaniasis — the symptoms of which can range from moderate to deadly. Visceral leishmaniasis, or black fever, damages the liver and spleen and can kill the victim within 20 to 40 days. The exact number of new cases of leishmaniasis per year is unknown, but the CDC estimates that there are 700,000 to 1.2 million 1,200,000 cases of cutaneous leishmaniasis and 200,000 to 400,000 cases of visceral leishmaniasis per year.

The parasites are mainly transmitted through the bite of a blood-sucking sand fly, and climate change is expanding the habitat of the insect from Latin America north toward the U.S. Leishmaniasis outbreak regions have now come within about 300 miles of the border.

Vaccination

Leishmania are single-cell organisms roughly the size of large bacteria. Like other parasites, they are more complex organisms than viruses and bacteria. For this reason, researchers have worked to develop a vaccine against leishmania and similar parasites for decades without success. The new research leverages the discoveries of doctors and scientists who have worked treating leishmaniasis in the field for years in outbreak regions. Their work has yielded intimate details about the parasite’s molecular makeup that render it vulnerable to a human immune reaction, which is drawn out by a fake virus in the vaccine.

The virus-like particle is harmless, and the body destroys it once it triggers the critical immune response that kills the leishmania. Other variations of the same kind of particle have already successfully made it through phase II human clinical trials.

Although conventional leishmaniasis treatment is mostly effective, it can leave small numbers of the parasite behind. These can cause relapses, spread the parasite — or both. A vaccine will be far more effective at halting outbreaks.