Holy Grail

Physicists around the world are on a mad dash to build a nuclear fusion machine that can replicate the Sun’s atom-fusing process and provide everyone with a low-cost, sustainable energy resource—effectively ending our dependence on fossil fuels.

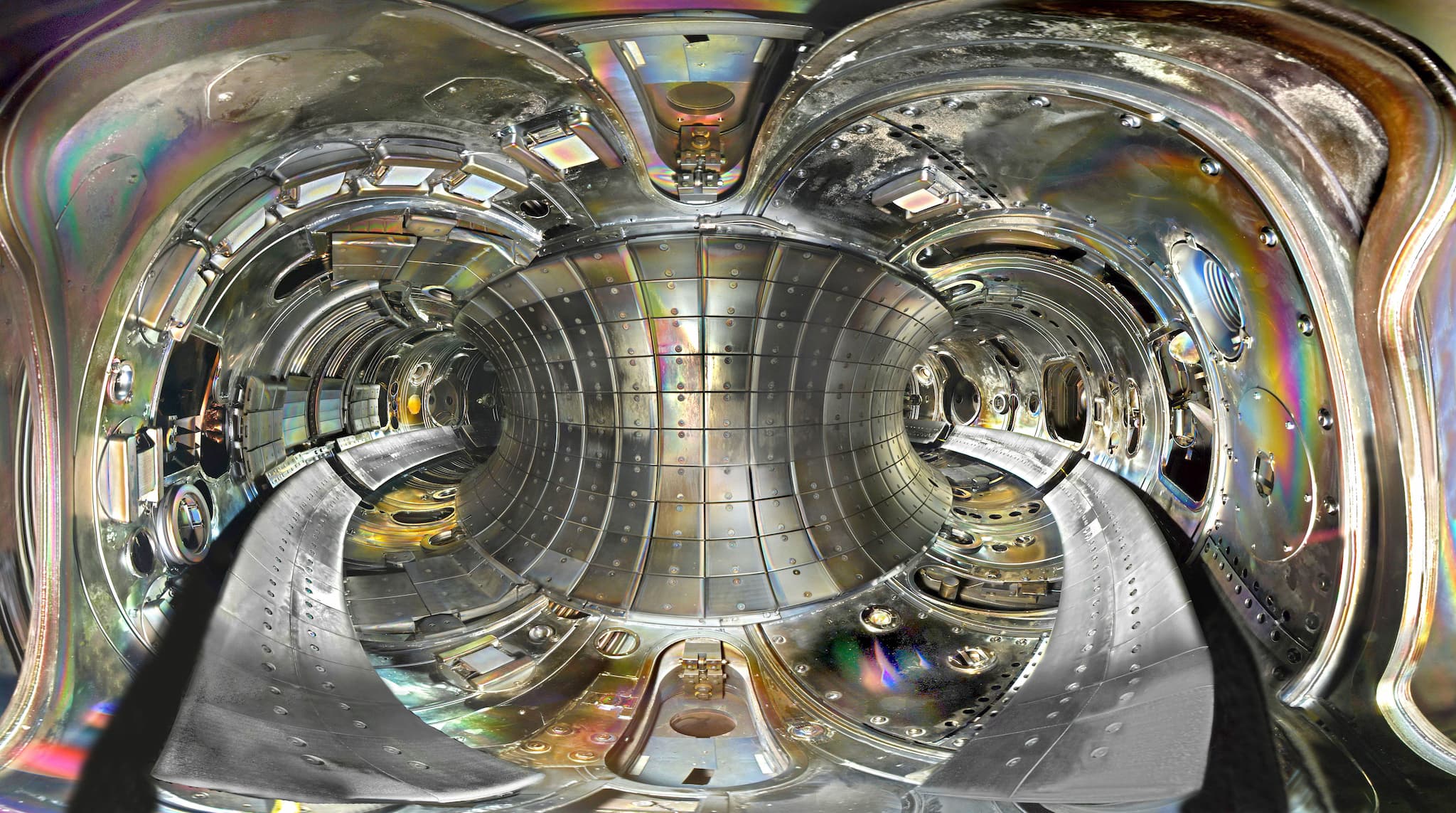

Replicating how the sun and stars create energy through fusion is essentially like putting “a star in a jar,” although there is no “jar” in existence that is not only capable of containing superhot plasma, but also low-cost enough that it can be built around the world—although it's not for lack of trying.

In fact, physicists are working on a new kind of nuclear fusion device that could be the most commercially viable design yet.

In a new paper published in Nuclear Fusion, physicists working at the U.S. Department of Energy's Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory (PPPL) assert that a model for such fusion device "already exists in experimental form - the compact spherical tokamaks at PPPL and Culham, England."

Spherical Tokamaks

Current designs for this so-called “jar” essentially call for doughnut shaped objects that come complete with powerful magnetic fields which suspend the plasma inside it, called tokamaks. It’s incredibly expensive to make and also hard to maintain, which is why physicists continue to develop new designs that will, hopefully, keep the cost down.

So far, there are two advanced spherical tokamaks in various stages of development. The first is the Mega Ampere Spherical Tokamak (MAST), which UK expects to be completed soon; the other is the National Spherical Torus Experiment Upgrade (NSTX-U) at PPPL, which went online last year.

“We are opening up new options for future plants,” said Jonathan Menard, lead author and program director for the NSTX-U.

But the devices, described in the 43-page paper, still have a long way to go. They must first be able to control the turbulence created after the plasma particles are subjected to electromagnetic fields, and also control how the superhot plasma particles interact with the device’s walls to avoid possible disruptions, which can happen if the plasma becomes too impure.

PPPL Director Stewart Prager said these two reactors, “will push the physics frontier, expand our knowledge of high temperature plasmas, and, if successful, lay the scientific foundation for fusion development paths based on more compact designs.”

Share This Article