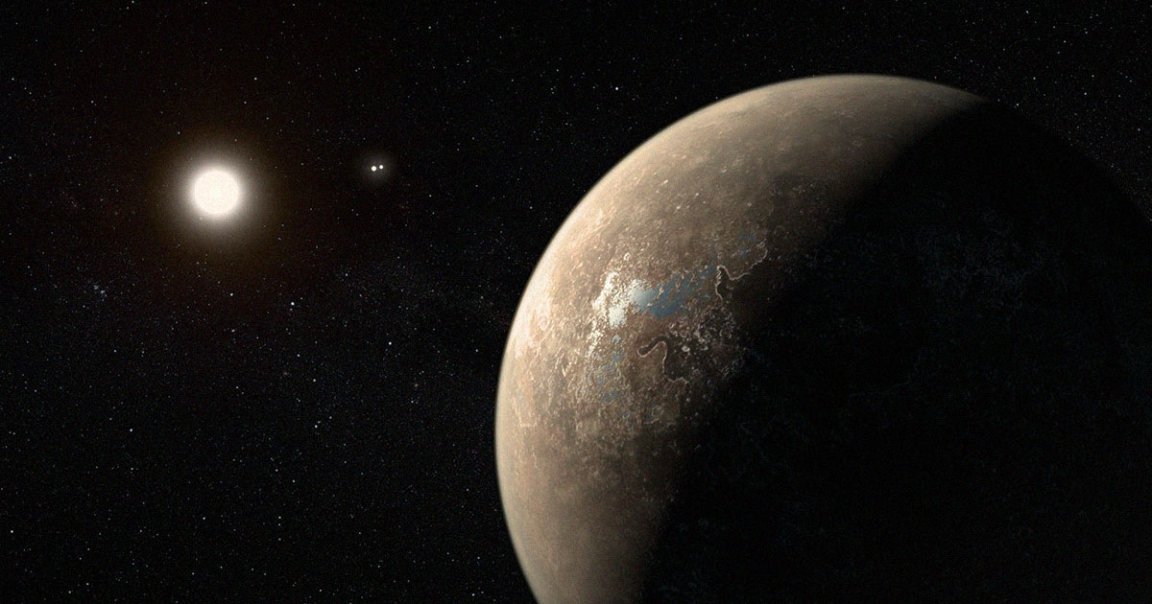

Interstellar Swarm

A team of scientists has come up with a wild idea to visit our closest star Proxima Centauri without putting human lives at risk — or spending tens of thousands of years to cover the 4.25 light-years or 25 trillion miles.

To put that number into perspective, NASA’s Voyager 1 probe has “only” covered 15 billion miles since it was launched almost half a century ago.

Instead of packing astronauts into the tight confines of a spacecraft, the team led by Space Initiatives startup chief scientist Marshall Eubanks suggests sending an entire swarm of minuscule spacecraft, which use the photons shot out of a giant laser as a form of propulsion, as Universe Today reports — a moonshot idea as inspired as it is fantastical. And now they’ve got the backing of NASA.

Light Show

The concept was recently picked up as Phase 1 for this year’s NASA Innovative Advanced Concepts, a program that’s given other out-there space concepts a platform and moderate amounts of funding.

“Of course, rockets are a common way to go fast,” he told Universe Today. “Rockets work by throwing ‘stuff’ (typically hot gas) out the back, the momentum in the stuff going backwards equaling that in the velocity increase of the vehicle in the forward direction.”

“The trouble is that we have no technology — no energy source — that would enable us to throw out a lot of stuff at anything like 60,000 km/sec, and so rockets won’t work,” he added.

Instead, the team is investigating the possibility of using a light sail, a form of propulsion that uses the forces exerted by photons instead.

Frontal Probe

Still, the thrust from just photons alone will be “weak,” as Eubanks explained, meaning that the “mass of the probes needs to be very small – grams, not tons.”

To give their swarm a push, the scientists propose using a 100-gigawatt laser to beam more light at these sails.

Unsurprisingly, it would take some time to figure all of this out. The team suggests the concept could be ready for development in a matter of decades to reach the star sometime after 2075.

“We want to look for signs of biology and even technology, and so it would be good to get probes very close to the planet, to get good pictures and spectra of the surface and atmosphere,” Eubanks told Universe Today.

“That will be tough for one probe, as we don’t know very well where the planet will be 24-plus years in the future,” he added. “By sending a bunch of probes in a spread, at least a few should get close to the planet, giving us the close-up view we want.”

More on light sails: Harvard Scientist Thinks He Has Found Alien Meteor Fragments