Rediscovering the Macrauchenia

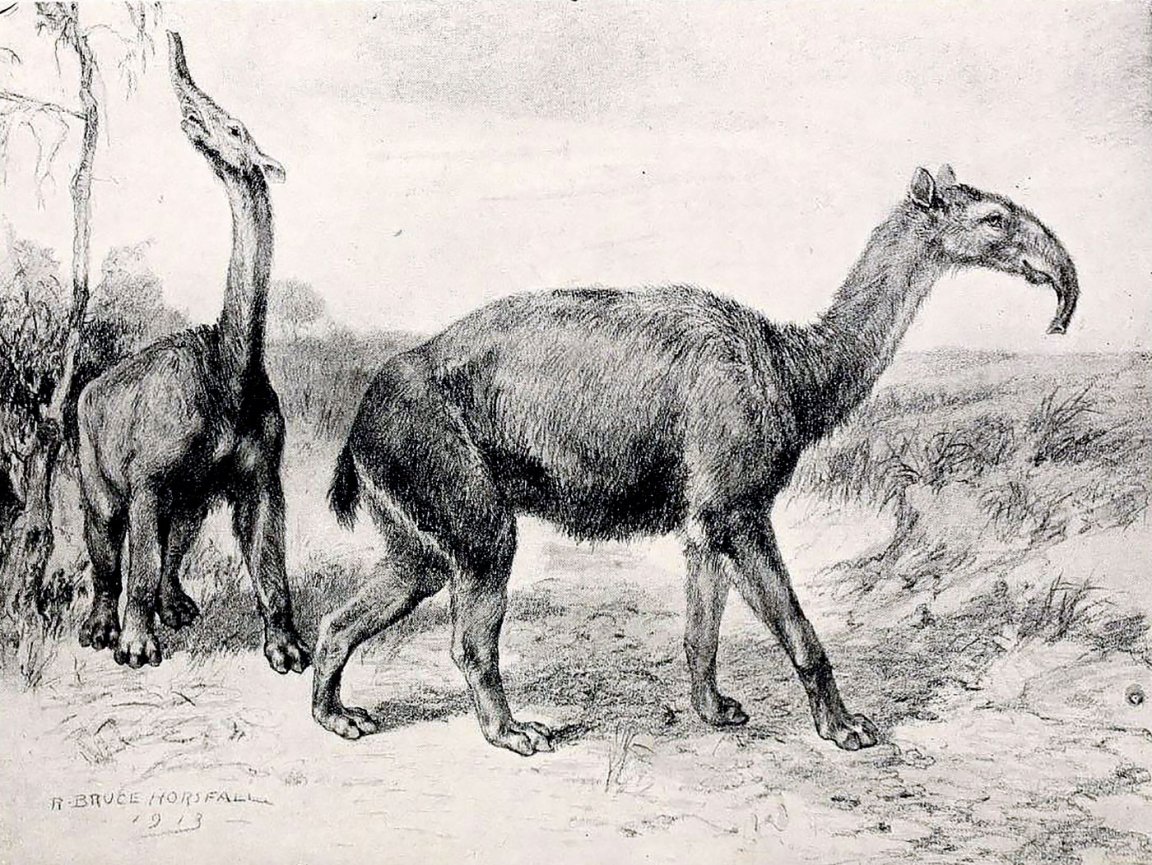

Charles Darwin discovered the bones of Macrauchenia, which went extinct toward the end of the Ice Age, in 1838 while digging in Patagonia. To him they seemed to belong to a kind of prehistoric llama. The remains were analyzed later on by the top anatomist in the UK, Richard Owen, who named the mystery mammal Macrauchenia patachonica. Although Darwin was right that there were some similarities with the llama, Macrauchenia didn’t appear to be a good fit with any existing group of mammals.

Counter-intuitively, the discovery of more fossils clouded the picture instead of clearing it up. Finding a nasal opening that signaled a trunk on the animal’s face resembling a tapir’s caused paleontologists to categorize Macrauchenia as a litoptern. This group of South American mammals arrived on Earth soon after the non-avian dinosaurs died out, and stayed until the end of the Pleistocene period. Perhaps the strangest thing about this group was that they superficially resembled animals found elsewhere in the world — such as elephants and horses — but evolved independently in South America.

However, of all of the mysterious factors surrounding Macrauchenia‘s identity, the strangest was that attempting to trace the animal’s origins through the bones — a process that was usually successful for paleontologists — wasn’t working. The relative isolation of South America, much like that of the Galapagos Islands, allowed evolution to create mammals that were confounding to scientists.

![*1* [Evergreen] A Strange Creature Discovered by Darwin Has Baffled Researchers for Decades](https://futurism.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/evolutionary-tree_v3.png?strip=all&quality=85)

Technology Clarifies Past, Future

The mitochondrial genome of any creature reveals matrilineal inheritance — and, therefore, can reveal siblings and other relatives with common female ancestors. The newly sequenced matrilineal genome divulged a sister taxon to the Macrauchenia and its litoptern family: perissodactyls. Also called odd-toed ungulates, this group includes horses, rhinos, and tapirs.

Westbury and his team also found that the two branches of the larger tree diverged around 66 million years ago as the Age of Mammals began. Macrauchenia was one of the last inhabitants of a group that arose just after dinosaurs such as Triceratops and Tyrannosaurus disappeared forever. This transition away from the age of the dinosaur and into the age of mammals is a classic illustration of the way that catastrophic extinction is really only catastrophic from a certain point of view; for survivors, it is simply a new and different era. The solution of the Macrauchenia mystery after almost 200 years is a testament to technology marching on, allowing scientists to understand our planet’s history. The more we know about the Earth’s past, the more mysteries (past and present) will become solvable.