Snail’s Minds Rendered Spotless

In the U.S. alone, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is estimated to affect about 8 million adults every year. Whether these individuals are struggling with events from a battlefront or a violent past encounter, they are likely to have at least two kinds of memories associated with their trauma — associative memories and non-associative memories.

Associative memories contain important information about the traumatic event, like who hurt you, or perhaps where the event took place. Non-associative memories, on the other hand, are about details that are not directly related to the traumatic event, but can still trigger symptoms of PTSD. But now, scientists have found a way selectively delete non-associative memories while retaining associative ones — at least in snails.

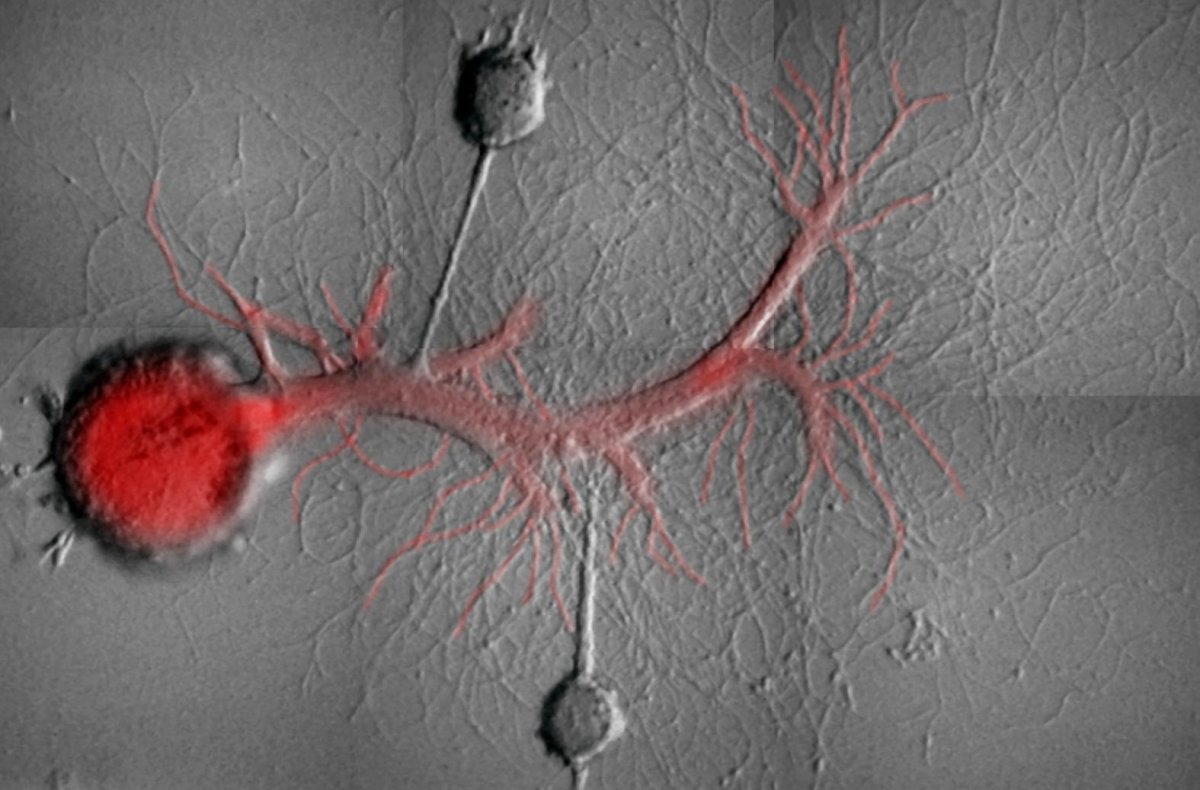

They were able to do this by blocking various molecules associated with an enzyme called Protein Kinase M (PKM), which is critical for maintaining long-term memories. Researchers recently reported in the journal Current Biology that they were able to erase different kinds of memories by blocking different molecules associated with PKM, and were even able to erase specific memories by blocking certain variants of these molecules.

“By isolating the exact molecules that maintain non-associative memory, we may be able to develop drugs that can treat anxiety without affecting the patient’s normal memory of past events.” Jiangyuan Hu, a co-author of the paper, said in an interview for a Columbia University press release.

Mastering Memory

While the team is hopeful that these methods will be as effective in humans as they were in snails, many more studies are needed before we get to that point. And, as yet, the team isn’t sure that the memories they erased are gone forever — only further research can clarify this issue.

This line of research may hold incredible promise for people suffering from PTSD, other mental health issues caused by traumatic events, and even drug addiction. However, this is a delicate area. Memories serve a purpose in most cases, and if we erase bad memories we may find ourselves making the same mistakes. In addition, some theorize that it’s not the memories per se that are the problem — it’s the recall process gone awry that causes the trauma to be re-experienced.

Furthermore, it isn’t clear how successful scientists will be at erasing only specific memories when, by their very nature, memories are interlinked with one another. Even if they can, will all of a person’s other memories make sense in context when one life-changing yet negative experience is suddenly gone?

Still, the team believes that the only way we can know if erasing memories is a viable medical strategy is by studying it. “Our study is a ‘proof of principle’ that presents an opportunity for developing strategies and perhaps therapies to address anxiety,” co-author Samuel Schacher said in the press release.