Don’t You Forget About Me

We all have them: Memories we’d just rather forget. A particularly humiliating experience, like that time you peed in the public pool or when you face-planted in front of that girl you were totally in love with.

Oh, wait…those are my memories.

The point is, there are certain experiences that can exercise an outsized, maybe even debilitating, influence over the rest of one’s life. And all kidding aside, there are those who have suffered from terrifying and traumatic life events that color and taint their perceptions (to their great detriment). Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) is just one such condition—common to military veterans, war refugees, and victims of rape and other violent crimes.

Now researchers at Stony Brook University may have found a way to actually manipulate memories. If it stands against additional review, it will be a finding with enormous implications, ranging from reassembling shattered lives to overcoming the memory-loss effects of Alzheimer’s Disease.

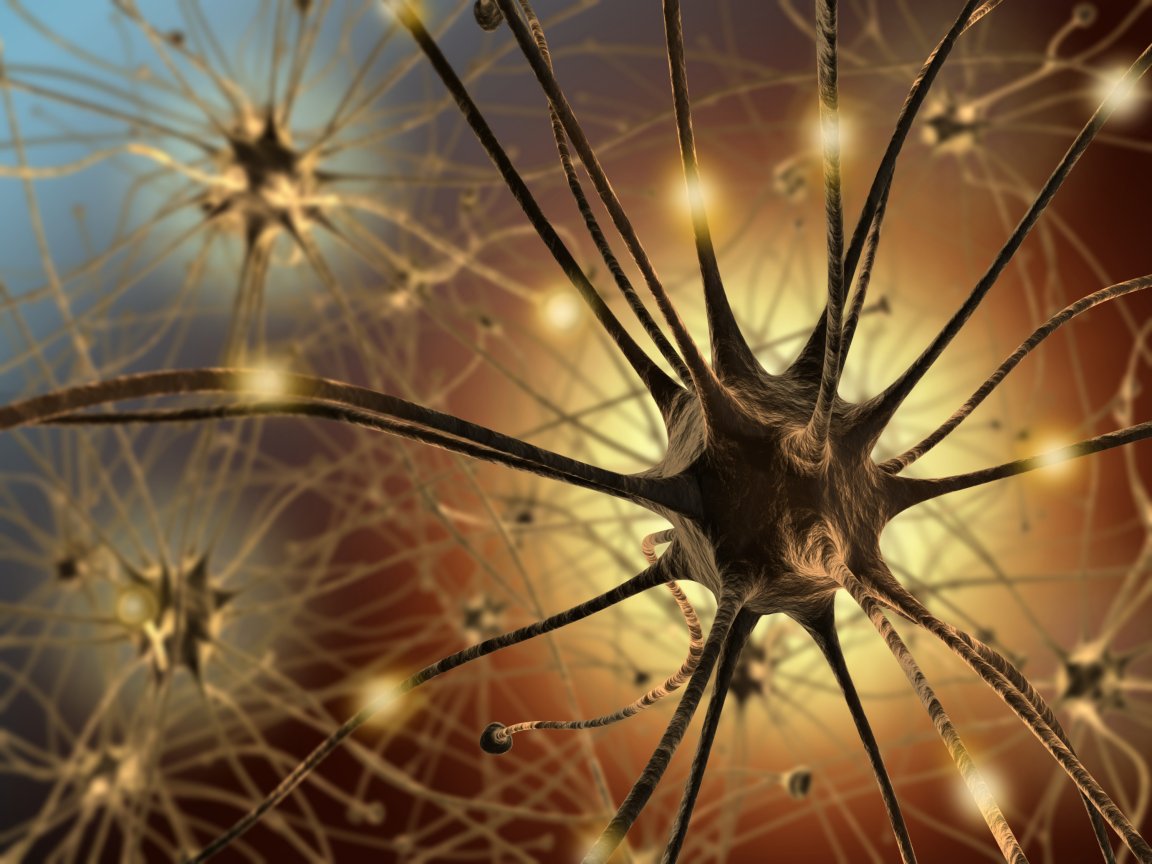

The new research focused on “tuning” memories by controlling acetylcholine, a neurotransmitter used by the brain in signaling memories. Emotional memory, it is believed, is seated in the amygdala, a part of the limbic system. Acetylcholine is transmitted to the amygdala via cholinergic neurons. Other research has suggested that these neurons are also affected by neurodegenerative disorders, and that amplifying cholinergic activity in the amygdala can enhance emotional memories and their recall.

Always Something There to Remind Me

The study, which was published in the journal Neuron, used optogenetics to stimulate certain cholinergic neurons in mice—they heightened its production during the formation of a traumatic memory, which doubled the period of time that the memory subsequently lasted. In a second test, they did the opposite, suppressing amygdalar acetylcholine during a traumatic experience.

They found that, far from producing a fear response, they had actually erased the painful memory altogether.

“This second finding was particularly surprising, as we essentially created fearless mice by manipulating acetylcholine circuits in the brain,” says Lorna Role, professor of neurobiology and behavior at Stony Brook.

Further research will seek to find ways to manipulate these cholinergic neurons in a way that doesn’t involve drug therapy; they are crucial to memory-formation, and it wouldn’t do to tamper overmuch with these important brain mechanisms.

But it opens the door to enhancing or diminishing memories—memory control, essentially, which could be a remarkable therapeutic option for victims of violence, sufferers of PTSD, and even those experiencing memory loss, amnesia, or cognitive decline. Of course, it also conjures darker images of Orwellian dystopias where we manipulate minds and memories, rewriting reality.

But I prefer to think of its positive benefits and imagine all the good such research can do in repairing broken lives.